First Sino-Japanese War still holds lessons for historians

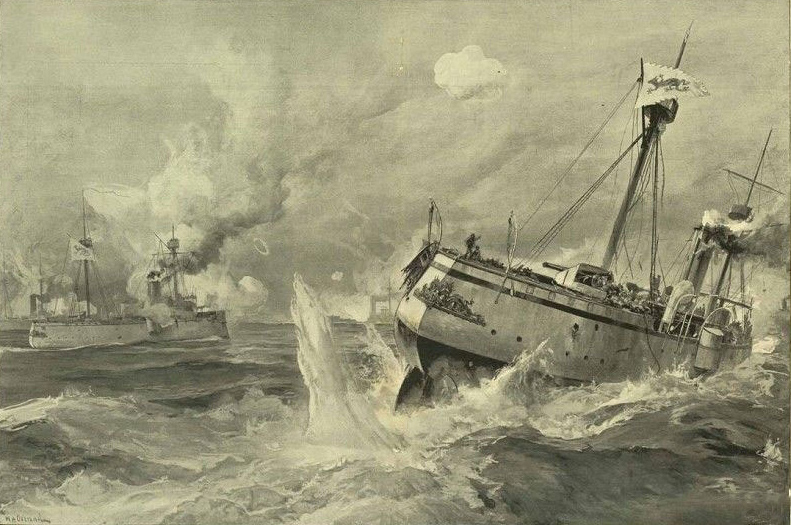

This illustration depicts the Battle of the Yalu River in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95).

The crushing defeat of the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), which ended 120 years ago, marked a turning point in the history of China’s national defense. As the nation commemorates this important anniversary, it is vital for scholars to reflect on the war and the lessons it has to offer.

Different strategies

The First Sino-Japanese War is commonly known in China as the War of Jiawu, which refers to the name for the year 1894 using the traditional Chinese sexagenary cycle of years.

It started with the Battle of Pungdo on July 25, 1984, and ended with the fall of Weihaiwei, part of present-day Weihai, Shandong Province, on Feb. 17, 1895.

The seven-month conflict ultimately resulted in the total destruction of the Qing navy. It is worth noting that the Qing’s Beiyang Fleet lost all of its battles with the Japanese Grand Fleet— at Pungdo, the Yellow Sea and Weihaiwei—and did not manage to sink a single Japanese ship.

When examining the First Sino-Japanese War, one thing that stands out is the stark contrast between the two military systems. After the Meiji Restoration, Japan established a modernized military system that ensured smooth implementation of military policies and orders. Before the war, the Imperial General Headquarters, Japan’s supreme war command, was brought into being, which was charged with the coordination of land and naval forces against China.

The Grand Fleet’s infrastructure and command systems were highly modernized and superior to the Beiyang Fleet. By contrast, the Qing navy still clung to feudal military institutions, which were characterized by disorder, low efficiency and uncoordinated administration.

After the outbreak of the war, the Qing court failed to establish a unified command institution. The army and navy fought separately, and each province combatted the Japanese forces alone. In short order, they were crushed one after another by the united Japanese land and naval forces.

In terms of firepower and warship performance, there was actually not much difference between the Beiyang Fleet and the Grand Fleet, but the efficacy of scientific technologies can only be maximized when they are integrated into the social system.

The Qing regime’s failure in the First Sino-Japanese War was by no means a simple matter of warships and firepower. Deeper down, it was a test of Qing institutions.

Furthermore, the First Sino-Japanese War exemplified the triumph of advanced naval strategies over backward concepts. During the war, the Imperial General Headquarters laid down modern, winning strategies for the navy.

Emphasizing naval supremacy and decisive sea battles, they focused all efforts on winning control over the Yellow Sea and the Bohai Sea. This was an aggressive strategy Japan formulated based on US military theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan’s concept of sea power, putting the Japanese forces at a preemptive, advantageous situation from the very beginning.

By contrast, the Qing court had never put forward any explicit naval strategy, but simply ordered the Beiyang Fleet to tenaciously defend the Bohai Bay, thus relinquishing the initiative in naval warfare.

Li Hongzhang, viceroy of Zhili in present-day Hebei Province and Beiyang minister of commerce, adhered to deterrence strategies and proposed the principle of “protecting warships to subdue the enemy,” reducing the Beiyang Fleet’s role to passive defense.

The utterly different concepts of operations between Qing China and Japan could not be divorced from the academic accumulation of the two navies. Before the war, Chinese academia and the navy still rested on naval strategies specific to the 1870s and 1880s, with little regard for the potential of sea power theory. Japan, on the other hand, had mastered the epochal theory and firmly carried it out in the war.

Also, tactical innovation was vital. After the mid-19th century, navies increasingly began to rely on ironclad warships, which were propelled by steam power and equipped with breech-loading rifled guns. Advancements in warship maneuverability and firepower shifted the focus of naval tactics from traditional lines of battle to high mobility of forces and weapons. The single-line formation was proven to be most practical and effective.

Twelve warships were arranged according to their speed into two single-line formations, which best utilized the maneuverability of Japanese warships and strong firepower of broadside vessels, giving the fleet the initiative in combat. The undoing of the Beiyang Fleet was due to its adherence to the passive collision tactics typical of the Age of Sail.

Historical data

Studies of the First Sino-Japanese War must be grounded in a wealth of informative, reliable historical data. Because many Qing military and political figures and patriotic intellectuals participated in or witnessed the war, their essays and journals are important primary sources.

In recent years, the National Codification Committee of Qing Dynasty History organized and published many related materials. Local chronicles are also important documents for historical research, but academics have not made full use of them.

Unearthed artifacts, as “living fossils” of history, also deserve high attention. The cultural objects salvaged from the cruiser Zhiyuan will help solve many historical mysteries.

In addition, special attention should be paid to discovering and organizing Manchu documents.

During and after the First Sino-Japanese War, foreigners in China wrote a wealth of travel journals and memoirs, some of which kept a faithful record of Japanese forces’ atrocities.

For instance, British James Allan’s Under the Dragon Flag: My Experience in the China-Japanese War presents firsthand accounts of how the Japanese army committed the massacre in Lüshun, Liaoning Province, and serves as hard evidence against the Japanese aggressors.

Scottish missionary Dugald Christie’s Thirty Years in Mukden gives details about how Qing General Zuo Baogui managed his army and sacrificed himself. Moreover, it includes accounts of atrocities Japanese forces committed in Mukden, which is present-day Shenyang, Liaoning Province.

The First Sino-Japanese War also captured the attention of numerous newspapers at home and abroad. Shanghai News (Shen Bao), North China Daily News, the New York Times and The Times all covered the war. They are also important sources of historical data.

In addition, Western military textbooks and military theory monographs translated during the Self-Strengthening Movement (1861-95) can also reflect the wide gap between Chinese and Japanese navies in academic accumulation. Therefore, military textbooks and translations of the late Qing Dynasty are also valuable.

As the aggressor in the war, Japan has preserved a large quantity of original war archives that are indispensible to studies of the history. In recent years, Japan has made plenty of relevant historical documents public.

China in fact has limited archives and historical data concerning the history of the war, especially that of land battles, and Japan’s documents can partly fill in the gaps.

Moreover, the United Kingdom, Russia, Germany, France and the United States were all witnesses to the war. The British East Asian Squadron kept a watchful eye on the sea war. Russia mediated the China-Japan dispute over Korea. The UK and Germany were major manufacturers of principal warships of the Beiyang Fleet while France left a profound mark on the shipbuilding industry and naval schools of modern China. American journalists also provided detailed reportage on the Liaodong Peninsula battle. However, domestic historians have not sufficiently studied these archives.

Land battles

Over the last 120 years, historians have never stopped discussing the various aspects of the First Sino-Japanese War. However, it is of particular significance to reflect upon the war in light of the increasing complexity and uncertainty in the geopolitical and international situation of East Asia.

For a long time, however, too much emphasis has been placed on sea battles, while land engagements are often neglected, so research on the history of land battles in the war should be intensified. There is vast room for investigation into land battles, strategies and tactics, abilities and qualities of commanders, fighting spirit, and the weaponry of Chinese and Japanese armies.

Despite a large number of research achievements, limited historical data and inadequate research methodologies have made it difficult for scholars to raise creative viewpoints. Strategies and tactics of the Beiyang Fleet are also a focus of research, but few studies have shed light on the academic history of the navy.

Additionally, the fighting spirit of naval officers and soldiers, the utilization of torpedo boat formations, and horizontal comparison between the Beiyang Fleet and the East Asian Squadron are also worth exploring. It is realistically important to examine tactics in the sea battle on the Yellow Sea, the Lüshun Massacre and the sinking of the cruiser Zhiyuan from new perspectives.

Jin Lixin and Xie Maofa are from the Academy of Military Sciences.