History of peasant revolts shines light on nation’s evolution

The Red Turban Rebellion led by Zhu Yuanzhang

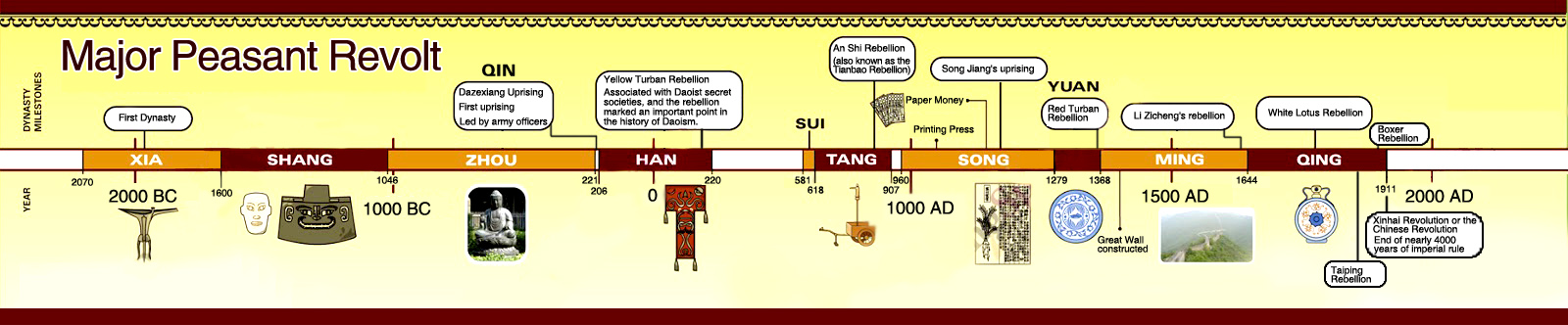

Timeline of major peasant revolts in Chinese history

In the global context, pre-modern history has traditionally focused on elites and major events, whereas the ordinary peasants who made up the vast majority of the population are hardly mentioned. Since the advent of modern times, impoverished people have gradually come to the fore, playing an increasingly prominent role in various social movements.

Out of many schools of thought, Marxism upholds the decisive role of material production in historical development, so the group that is most directly related to the creation of social products is also valued.

Study in twists and turns

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the history of peasant revolts has undergone uneven development as a discipline. After the Cultural Revolution, society strived to right the wrongs of the past. Accordingly, this branch of study also began to reflect on its over-politicized past and stress objectivity. Thus, it enjoyed a boom shortly after the fall of the Gang of Four.

However, in the late 1980s, Western theories swept through Chinese academia, inspiring numerous new research areas, issue orientations and research methodologies. Afterward, this popular discipline that once affected the political life of the nation no longer captured the interest of scholars.

If political implications are set aside, we see that the history of peasant revolts marks the transition of traditional historical studies into a modern phase by shifting the focus of historical study from elites and political events to ordinary people and social structure. The shift is not only in accordance with the scientific approach modern historians utilize to build theories and frameworks but also reveals the strong desire of scholars to establish a localized system of historical study.

Though in individual research some are confined by personal judgments, narrow perspectives or simplistic methodologies, such a shift represents a dedication to understanding the dynamics and characteristics of Chinese historical development.

Despite the progress, Chinese historical research sometimes blindly follows Western practices and rigidly applies Western theories, while homegrown traditions are often overlooked and the discussions on major issues become rare to the point that Chinese features seem blurry.

Though peasant revolts have been common throughout world history, China may be one of the nations that has had the largest, most widespread and most frequent outbursts. More than other civilizations, Chinese civilization has a history of cyclical regime change brought by peasant insurrections. The study of peasant revolts is one perspective to interpret core issues and main decisive factors of Chinese history, examine Chinese history as a whole, and understand Chinese civilization within the framework of world civilization.

Causes of revolt

The frequent occurrence of peasant revolts in China was closely associated with its geography, economy, social structure, ideology and culture. The wide and flat terrain allowed peasants to embark on a long-distance migration. The agricultural-based economy guaranteed sufficient manpower for armed insurrection. Also, feudal society separated peasants and put them under direct control, thus creating an institutional opportunity for farmers to get rid of local bureaucrats and merchants to form alliances.

In addition, Confucian culture advocates meritocracy, as it was boldly shouted out: “Are the military and political leaders born with noble blood?” in the Records of the Grand Historian, serving as an ideological support for peasant revolts.

One of the causes of peasant rebellions in ancient China was the long-term conflict between ecological environment and agricultural finance. While East Asia is rich, the region was often afflicted with floods, droughts and plagues. Famine and war took a toll on the agricultural economy and finance.

To make things worse, in order to strengthen control on the Central Plain and peripheral regions, the ruling class would increase taxes. This practice placed a heavier burden on peasants and led to regional uprisings that often later coalesced into nationwide resistance.

Interestingly, though the main participants were farmers, leaders of peasant revolts were usually from a marginalized social group, given that farmers were mostly confined to the land by policies and thus lacked of mobility, knowledge and capacity to fight on their own.

Those who had an insecure status, at various times living as a farmer, servant, merchant or even intellectual, constituted the marginalized social group. They became familiar with regional geography and had a better understanding of society, enabling them to agitate for rebellion.

For instance, in the peasant rebellion against the Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368), rebellious leaders appeared to have diverse occupations: Zhu Yuanzhang was a monk; Chen Youliang, a fisherman, and Zhang Shicheng, a salt smuggler.

Some peasant revolts were led by religious leaders who promoted beliefs outside the orthodox ideology.

Ancient Chinese society

The study on the history of peasant revolts is conducive to understanding the political character and historical path of ancient Chinese dynasties. The Ming regime, unlike other civilizations in the same period, didn’t adopt an outward state policy. Instead, it chose conservative policies and started to construct the Great Wall on a large scale. It was because Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), was originally from the undeveloped Huaihe River, where the Han people were threatened by the constant invasion of the northern tribes.

Studying peasant rebellions will also provide context concerning ancient China’s economic, military power and status in the world arena. As for China’s status, we often study the established dynasties. However, the losers in the power struggle are also worthy of our attention. For instance, Chen Youliang had well-equipped fleets while Zhang Shicheng was able to trade overseas and was believed to have the strongest navy and commercial ships at that time.

When Zhu Yuanzhang, who valued armies more, defeated his rivals and took power, further development of the navy and trade was hindered. Though people marvel at the grand achievements of Zheng He and his expedition, they cannot help but wonder about the opportunities the Ming regime had. Sadly, the power and possibilities of peasant insurrections were also rarely noticed.

Central regimes were usually more concerned with peasant revolts than border wars due to their direct and fundamental impact. Under such a political and military framework, ancient China gradually formed the tradition of prioritizing domestic affairs over border maintenance. The efforts to maintain inland and border balance with a bias toward the former hinted at Chinese civilization’s introverted character.

Interdisciplinary research

Within East Asia, geographic conditions vary greatly. When cross-referenced with major events and timelines, we can see a clear regional historical pattern. In fact, though peasant revolts were common in different locations throughout Chinese history, on the whole, places with harsh ecological environments and poor economic conditions seemed to have rebellions that were more frequent and on a larger scale.

It is apparent that the study of peasant revolts in ancient times should explore more perspectives, such as regional development and the relationships among ecology, economy, politics, military, society and culture, rather than simply analyzing it from the viewpoint of national institutions. The history of various regional peasant revolts provides a geographical perspective to understand the imbalanced development of ancient Chinese history.

Since peasant insurrections were also related to ecological environment, we need to stress field investigation to complement document research. In addition to gaining first-hand experience, it may help correct the unreliability of records due to a impartial or poor understanding of the impoverished class.

As a complex subject, it requires interdisciplinary research to present a comprehensive and professional analysis. For example, ecological sudies need geographical information while examining plagues requires medical knowledge.

In sum, the history of peasant revolts needs to respect historical facts while adopting interdisciplinary methodologies, combining documents and field research, and applying institutional and regional perspectives to better demonstrate its significance in Chinese and world history as well as to inform our perception of the patterns of Chinese society.

Zhao Xianhai is from the Institute of History at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.