Republican era brought drastic changes in belief

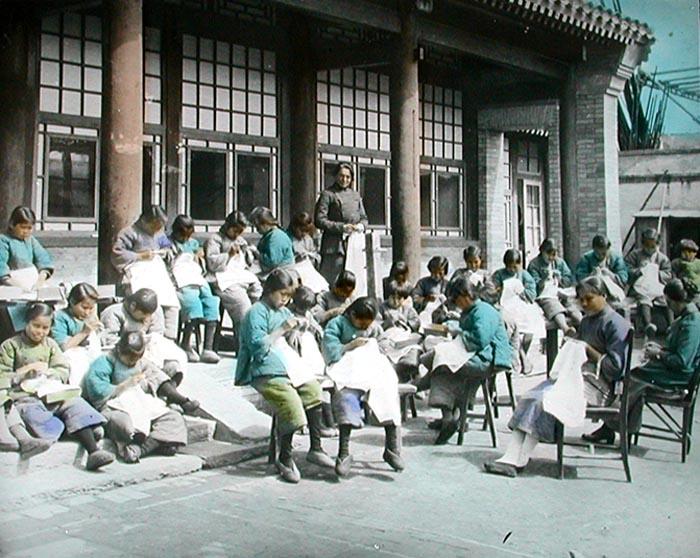

Girls learn embroidery at a church school in the Republican era.

The establishment of the Republic of China (1912-49) put an end to the long-lasting absolute monarchy and also fundamentally shook the state ideology that supported its rule. The ensuing wave of political transformation brought unprecedented changes in social beliefs, such as ancestor worship, Buddhism and Taoism.

Ancestor worship declines

The worship of ancestors is one of mankind’s most primitive beliefs. In traditional Chinese society, the Confucian ethic of filial piety and paying respect to “heaven, earth, emperors, parents and teachers” provided a theoretical basis for its continuation and development. In this vein, a set of complete and orderly rites for showing reverence to one’s ancestors were developed and held sway in Chinese society for centuries.

However, in modern times, the traditional patriarchal clan system was severely challenged as many intellectuals began to fiercely criticize the custom from a theoretical standpoint, eventually precipitating its decay.

First, ancestor worship lost the institutional and official support it enjoyed under imperial rule. When the Nationalist government revised its civil code in 1929, it preserved the family law but focused more on parents’ responsibility and obligations while it mandated equal inheritance rights for men and women, challenging traditional patriarchy from a legal perspective and accelerating the disintegration of the clan system.

Second, Confucianism, the theoretical and spiritual foundation of ancestor worship, was no longer the prevailing orthodoxy. During the early years of the Republic, Confucianism was subject to harsh public criticism from intellectuals, such as members of the New Culture Movement. It was evident that ancestor worship would not be spared.

The emerging educated class considered ancestral rites superstitious and backward customs that served the anti-intellectual motives of imperial rulers, arguing that they violated the human rights of descendants and constituted a total waste of the masses’ money and energy. It was even blamed as the “culprit” for undermining society.

Third, social turmoil made it unfeasible to carry out the rituals. In the traditional clan system, several components were crucial to ancestor worship, including the pieces of land and the number of ancestral halls owned by a lineage, the frequency and scope of sacrifices, and an unbroken line of descent. In agrarian society, land was the material basis and main source of income. Only when it owned enough land was the entire clan capable of holding grand sacrificial ceremonies.

By the end of the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911), the economy in rural villages was on the verge of collapse while loss of clan land was common, so few possessed sufficient land to connect the whole lineage. At the same time, peasant revolts in the 1920s subverted clan power and prominent clansmen. These uprisings seized ancestral halls and abolished clan rules, disintegrating or destroying the entire clan system and kinship solidarity, which also adversely affected the practice of ancestor worship.

Foreign religions

Buddhism and Taoism, two important forms of traditional Chinese religion, had always been the core of Chinese social beliefs. However, in the midst of social transformation, their glamor gradually faded in the face of tremendous challenges and impacts. In contrast, Christianity and Islam started to gain footing in many regions with a relatively stable group of believers, and their presence was inclined to further expand.

The fall of traditional religious beliefs can be attributed to three major elements—poor organization plus diminishing religiosity, large-scale destruction of temples by local officials during the late Qing and early Republican period, and the damage brought by revolutions and wars.

After the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, scholars strongly advocated that science become the means of overcoming ignorance and superstition. To that end, they initiated social reforms to dismantle temples and shrines linked to feudal superstition.

In the New Culture Movement, some radical intellectuals sought to wipe out any forms of feudal superstition, leading to a nationwide destruction of Buddha statues, city god temples or sacrificial halls, as well as the occupation of shrines and abbeys and the expulsion of monks and nuns.

Though Buddhist leaders strove to revive the religion through innovation, systemic reform of the monastery system and promoting education, its fate was sealed due to lack of official support, unified organization and doctrines that conformed to the trend.

As for Taoism, some faithful believers in rural areas still worshiped the kitchen god Zao Shen, the god of wealth Cai Shen and the earth god Tu Di, especially in Yunnan, Sichuang, Fujian and Anhui provinces. Taoist priests were often consulted on a variety of religious activities, such as offerings to local spirits, the location of graves, building a new home, expelling demons, praying for rain or sun, weddings, birthdays of the elderly, and funerals.

Western religions were introduced to China by missionaries in the late Qing era, but they failed to take root. However, following the establishment of the Republic of China, Western religions experienced rapid growth. Congregations swelled as churches were built across the country.

This phenomena was closely related to the vast number of missionaries in China who helped bridge the cultural differences between the East and West, facilitate communication and disseminate doctrines. In addition, they were keen on setting up charities and schools, giving rise to its fame and support among the populace.

According to statistics from the year 1914, Christian churches opened more than 12,000 schools and recruited more than 250,000 students. Also, Catholic churches were committed to funding orphanages, hospitals and other welfare charities. Last, state policies allowed freedom of religion, removing institutional barriers to Western beliefs. The inflow of newspapers and journals prepared the public for their rapid development.

Folk beliefs in chaos

In the late Qing era, folk beliefs were diffused and pluralistic. A wide variety of beliefs in gods, spirits and ghosts coupled with such practices as ancestor worship, imperial or state ritual, divination, and geomancy were deeply involved in all aspects of social life.

With the promulgation of a set of laws titled “Standards for Preserving and Abandoning Gods and Shrines,” the Nationalist government declared superstition an obstacle to progress in 1928 and set out to condemn superstition in all forms. It was followed by several other anti-superstition edicts attacking divination and other magical practices. Thus, belief in gods and superstitions, to an extent, died away.

The impact of the education system on the worship of Wenchang, the Taoist god of culture and literature, is a prime example of the effect institutional reform had on popular belief. In ancient times, Chinese literati paid formal reverence to Wenchang Dijun for their scholarly achievements, official rank or wealth. After the First Opium War (1840-42), the practice of Wenchang worship appeared to be on the downturn. In 1905, after the imperial examinations were abolished, Wenchang worship lost its institutional support and was no longer popular. After the emergence of the New Culture Movement and the development of a new education system, Wenchang worship became a rarity.

Another example would be the impact of urban management on the city god. He was the deity people turned to for supernatural assistance during droughts, floods or other crises that were beyond direct human control. However, modern urban development depends on human management rather than supernatural protection, so naturally worship of the city god came to an end.

The introduction of Western ideas, science and democracy at large liberated people’s minds. The public gradually came to realize the ignorance and harm of feudal superstition. In the Republican era, the practice of arranged marriages became less and less common, so young men and women no longer worshiped Yue Lao, the Taoist matchmaker god of love and marriage.

In addition, with the end of imperial rule and the rise of freedom and democracy, those in power no longer relied on the Jade Emperor to legitimize their rule.

Though folk beliefs were ebbing, traditional ideas still had a profound impact on the local level. Plus, in the secularization of natural and personal gods, a great number of witchcraft, fortune-telling, astrology, geomancy and divination tools were employed to strengthen the spiritual power of these gods. Superstitious activities were seen as an important way of communicating with the gods, thus it was impossible to eradicate them in a short time.

To conclude, during the period of the Republic of China, social beliefs transformed greatly. On the whole, there was a coexistence of old and new practices even as traditional beliefs declined. Christianity and Islam achieved some development, altering the landscape of socioreligious beliefs at that time. However, ancestor worship, traditional religions and folk beliefs still had a large number of adherents.

Futhermore, the power struggle between traditional and Western religions seemed to be a loose end. In a few cities, the growth in the number of Western religion believers outpaced that of tradition religions like Buddhism and Taoism, but in many rural villages, traditional religions still held sway. Finally, superstition was by no means ever really fully eliminated.

Zhao Yinglan and Jia Xiaozhuang are from the College of the Humanities at Jilin University.