Modern Chinese credit agencies vary from Western models

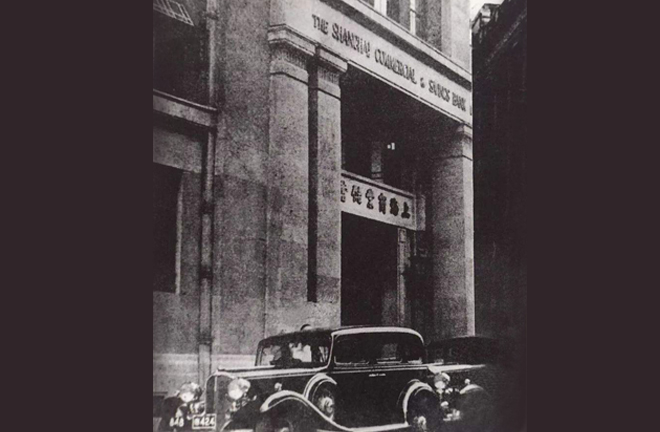

The Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank founded by famed modern Chinese banker Chen Kuang-fu, which instituted the first credit department in China Photo: FILE

In the contemporary world, it has become normal for banks to set up credit agencies and research centers to collect market information, probe clients’ credit ratings, and even compile and publish journals and books. The concept of the credit agency originated in the West and was introduced to China during the Republican Era (1912–1949). It had a long journey before it became popularized in the financial realm.

Emergence of credit investigation

With the thriving of modern industry and transportation, the mercantile agency gradually came into being. Due to the expansion of businesses and the development of long-distance trade, credit information gathered from networks of acquaintances as before was increasingly insufficient to meet growing needs.

The first mercantile agency was founded in New York City. In 1841, Lewis Tappan, a merchant who suffered great losses from the severe financial crisis of 1837 in the US, established Tappan & Co.. The company gradually evolved into R. E. Dun Co., which was dubbed one of the two major credit agencies in the US, together with Bradstreet Co., which was founded in 1849. Private-run credit agencies of this kind were predominant, a feature of credit investigation in the US at the time.

To banks, however, investigations by mercantile agencies were less targeted and secure, so they began to install such bodies by themselves as bank credit departments. The first bank credit department was set up at the Fourth National Bank of New York in 1890. Thereafter, it quickly spread throughout the financial community in the West.

Different business cultures resulted in different developmental paths for such institutions in Western countries. In Britain, commercial organizations tended to form long-term partnerships with a certain bank, so bank credit departments were not developed. Only a few bank clerks were charged with simple matters like handling documents.

In the US, on the contrary, companies usually maintained contact with many banks concurrently to raise more funds. Therefore, credit departments in American banks were larger, more complete and well-staffed.

In Asia, Japan was probably the first country to establish credit agencies. Bank credit departments and mercantile agencies emerged roughly at the same time. In January 1888, the Yokohama Specie Bank instituted the investigator system, marking the beginning of the construction of bank credit departments in Japan.

Pronounced Japanese banker Toyama Shuzo carried out an inspection of industrial and commercial development in the West between 1887 and 1888. After returning to Japan, he joined forces with four banks to found the Osaka Commercial Credit Bureau in 1892. In 1896, the Tokyo Credit Bureau was established with the support of the Bank of Japan as well as another 19 banks (the number reached 26 when the protocol was promulgated).

Representative of credit agencies in modern Japan were the Osaka Commercial Credit Bureau, the Tokyo Credit Bureau and the Imperial Credit Bureau, which was founded in 1900. Like bank credit departments, they published books and engaged in extensive social investigations apart from regular credit inquiries.

Introduction to China

Before Chinese-funded banks were set up in modern China, traditional Chinese financial institutions coexisted with their foreign counterparts for a long time. Both had their own ways of credit investigation.

Old-style Chinese private-run banks, qianzhuang, literally money houses, were exemplary of traditional Chinese financial institutions. They designated street clerks for credit investigation. In some regions, they sometimes needed to resort to chambers of commerce or guilds to obtain credit information on merchants.

Foreign financial institutions relied on subordinate investigation departments or mercantile agencies that foreign countries had established in China. Among these, Japanese credit agencies were notable.

In 1905, Japan superseded Czarist Russia to exert control over Northeast China through the Russo-Japanese War. In February 1908 and May 1911, it instituted the Manchuria Credit Office and Nisshin Credit Bureau successively in Dalian, Liaoning Province, in addition to the renowned Mukden Credit Bureau established in June 1917 alongside 12 of its branches in northeastern China. In 1910, the Yokohama Specie Bank also installed a credit department in Dalian.

In provinces with no Japanese-invested mercantile agencies, such as Guangdong and Hubei, Japanese business institutions, like chambers of commerce and even government bodies, such as consulates, became important organs for credit investigation by Japan.

Chinese-funded banks appeared later than traditional financial institutions like qianzhuang and piaohao, or exchange shops. Soon after the establishment of the banks, experienced qianzhuang managers were typically employed in bank management. In 1915, the government of Republican China released the Charter of the Bankers Association, stipulating that credit investigation was one of the matters that the association should deal with.

From then on, other banking associations proceeded to discuss setting up credit agencies. Newspapers and periodicals, such as Bank Weekly, also started to introduce Japanese and Western mercantile agencies and their investigation approaches.

In 1915, Chen Kuang-fu, who returned from overseas study in the US, founded the Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank and instituted the first credit department in China. In the same year, the Bank of Communications made the same move. Thereafter, many banks followed suit and made bank credit inquiry a common practice.

The banks investigated wide-ranging content, including the domestic and foreign economic and financial situation, loans and deposits, and even commodities in the market. Banks in Shanghai placed more stress on the three C’s, namely capital, capability and character, in the process of credit investigation, weighing the qualification of prospective borrowers comprehensively.

The investigation work was mainly completed by investigators, divided into indoor and outdoor investigators. Indoor investigators were responsible for gathering and organizing newspapers and periodicals and other files, while outdoor personnel conducted field investigations.

Among Chinese banks, the Bank of China and the Central Bank of China stood out in regard to credit investigation. In 1930, Chang Kia-ngau, father of modern Chinese banks, set up an economic investigation department, which was later renamed Economic Research Department, and published various books and periodicals, such as the Bank of China Monthly Review and the Financial and Commercial Monthly Bulletin of the Bank of China.

In 1933, after assuming the position of Governor of the Central Bank of China, Chinese banker and politician Kung Hsiang-hsi set up an economic research office to compile economic statistics, probe the industrial, commercial and financial sectors, collect and sort books and newspapers, aid in investigating other businesses, and carry out specialized studies on particular issues.

To streamline the situation of banks running separate credit investigations, realize resource sharing and protect trade secrets, the Shanghai banking community formed a Chinese credit society in March 1932 as a non-profit research institution. On this basis, the Chinese Credit Agency was established in June the same year, committed to investigating factories and shops, personal credit and the market. The membership consisted of 19 Chinese banks. Later it absorbed many foreign banks and enterprises and employed professionals from all fields as well as economists as advisors, substantially promoting the development of the credit system in modern China.

In 1937 after the war of resistance against Japanese aggression broke out, social turmoil fueled the demand for credit investigation instead, and the emphasis on material and information exchange and industrial alliances grew stronger. In the meantime, local mercantile agencies sprung up, while many provincial banks in Guangdong, Hunan, Anhui, Zhejiang and Shaanxi set out to institute investigation and research organs. By the 1940s, there were approximately 30 economic research institutions with 700–800 researchers in banks across the nation.

China-West differences

The development history of credit agencies shows that these institutions were a product from the rise of modern industry and transportation to adapt to changes brought by the long-distance, extensive commercial and trade development of traditional credit rating systems. They were created by Western countries, namely Britain and the US; Japan followed their examples; and modern China learnt from the West and Japan. Yet the development and nature of the agencies varied vastly in the latter two cases.

First, mercantile agencies were established earlier than bank credit departments in Western countries, but it was the other way around in Asian nations like Japan and China. This underlines the latter two’s underdevelopment in economy and commerce and their backwardness in commercial and financial institutions as a latecomer capitalist country and a semi-colonial nation, respectively.

The second difference lies in the relationship between mercantile agencies and bank credit departments. In the West, the relationship was loose, because its developed commerce determined that mercantile agencies were usually for-profit organizations, rather than serving banks only. In Japan and China, by contrast, the relationship was very close. Banks were not only initiators and organizers of mercantile agencies, but also their important members providing financial aid and other assistance. The non-profit nature of mercantile agencies in the two countries outperformed their for-profit nature, which was inseparable from their nations’ stage of economic and social development.

Liu Fenghua is from the Institute of History at the Tianjin Academy of Social Sciences.

edited by CHEN MIRONG