Chinese and Western rhetoric agree in multiple aspects

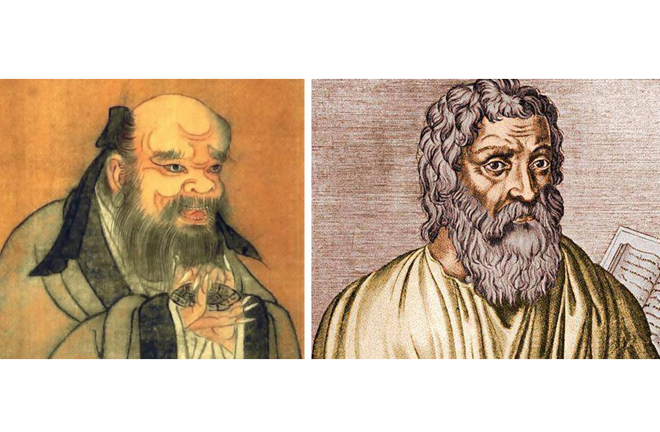

Above are Guiguzi (Left), a well-known strategist of the Warring States period, and Ancient Greek rhetorician Gorgias. Classical Chinese and Western rhetoric highly agree with each other on the role of rhetoric, particularly regarding the thoughts of Guiguzi and Gorgias. Both contended that rhetoric should aim to influence people’s thinking. Photo: FILE

In the general trend of globalization, knowledge and information continuously converge and mingle, while China and the West communicate with growing frequency. As simple expressions are insufficient for this type of interaction, linguistic rhetoric has gradually become more penetrative, showing strong discourse power. In this light, it is particularly important to comparatively examine Chinese and Western rhetoric, so as to associate and blend them.

Difference in research

Rhetoric studies in the West can be traced back to Ancient Greece in the 5th century BCE, onward through the heyday of Ancient Rome, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and its revitalization in the 20th century.

In the long evolutionary course of more than 2,000 years, rhetoric was like a queen, placed at the top of all arts and commanding the majority of, even all, disciplines. Later the queen was ousted and reduced to a courtier, even a servant, to supplement the three basic arts of logic, grammar and dialectics.

In the West, rhetoric has been regarded as one of the most dangerous tools for humanity, yet meanwhile a powerful weapon to promote the development of human civilization and society. Contemporary rhetoricians generally maintain that rhetoric is the study of how humans influence others through symbolic means. Where there is persuasion, there is rhetoric; where there is meaning, there is persuasion. Therefore, studies of rhetoric address a diverse range of domains.

Rhetoric studies in China also have a long history. From the voluminous writings of the pre-Qin period, we can find fragments that kept track of the ideas and rules of rhetoric. “The Twenty-fifth Year of Duke Xiang” in the Commentary of Zuo, or Zuo Zhuan, documented what Confucius said: “An ancient book says, ‘Words are to give adequate expression to one’s ideas; and composition, to give adequate power to the words.’ Without words, who would know one’s thoughts? Without elegant composition of the words, they will not go far.” Confucius’s argument contains a profound rhetorical philosophy.

In the 1930s, pioneer of modern Chinese rhetoric Chen Wangdao, while compiling the book An Introduction to Rhetoric, defined rhetoric as the need to adjust words to a theme and situation. His work led Chinese rhetoric to a qualitative leap. Chinese rhetoric gradually evolved into a modern discipline with a solid theoretical foundation and sound systems. Today it has abandoned the traditional narrow outlook that values skills and expressions over reception, broken the model of language ontology, and exhibited a cross-disciplinary and multi-dimensional trend.

Consistency in ancient times

The “sophistry” of Ancient Greece had much in common with the “lobbying” widely practiced during the Spring, Autumn and Warring States period (770 BCE–221 BCE). Legend goes that Western rhetoric originated from Sicily in Ancient Greece. At that time, sages rushed from one city-state to another, pursuing equality and freedom by persuading others and settling disagreements. The essence of classical Western rhetoric was oratory and sophistry, and the core function was persuasion.

The chaotic Spring, Autumn and Warring States period also witnessed the emergence of many itinerant sages and lobbyists. In his book A Brief History of Chinese Philosophy, renowned Chinese philosopher Feng Youlan (1895–1990) divided them into Confucians, swordsmen, debaters, and so forth.

According to The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons, China’s greatest work of literary aesthetics authored by writer Liu Xie (c. 465–c. 520), words should be pleasing. In order to make their advice accepted, lobbyists must move others through their speeches. In essence, lobbying was no different from the persuasion touted in the West.

In the Axial Age from about the 8th to the 3rd century BCE, debating was as prevalent in China as in Ancient Greece. The debate between Confucianism and Mohism sparked the contention of a hundred schools of thought during the Spring, Autumn and Warring States period. Chinese philosopher Lao Siguang (1927–2012) believed that Mohist theories hold up in comparison to contemporaneous Western thought and that the logic of the Logicians is as valuable as speculative metaphysics.

Many luminaries of Ancient Greece and the Spring, Autumn and Warring States period of China owed their official career to their eloquence. Whether Ancient Greek Sophists who became cultural heroes of the times for their brilliant speeches, or Zhang Yi from the Warring States period, for example, who helped Qin to dissolve the unity of the other states and hence paved the way for Qin to unify China, they rose to fame for their silver tongues in various social interactions.

Classical Chinese and Western rhetoric highly agree with each other on the role of rhetoric, particularly regarding the thoughts of Guiguzi, a well-known strategist of the Warring States period, and Ancient Greek rhetorician Gorgias. Both contended that rhetoric should aim to influence people’s thinking.

Guiguzi argued that those capable of rhetoric were able to control their mind and become masters of their mentality. Hence inspiring language, such as poetry, essays and speeches, could in fact evoke people’s virtues. Gorgias pointed out in his theoretical framework that using rhetoric as an art of persuasion was like being a duke of great power, who could manipulate emotions, attitudes and behaviors.

Moreover, the social functions of classical Chinese and Western rhetoric are quite similar. For example, Achilles, dubbed as the most excellent Greek for his eloquence, and Gorgias, the inventor of impromptu speeches, can be compared with such Chinese historical stories as that of Lü Xiang, an envoy of the State of Jin, going to Qin to declare the end of his friendly relations with the latter, and Chu Long, a minister of the State of Zhao, convincing Empress Dowager Zhao to send her son to the State of Qi as a hostage, in which the role of rhetoric in settling conflicts and disputes between vassals was evident. In war-ridden times, persuasion and debating as part of statecraft was just as important as war. Mastery of rhetorical skills could subdue the enemy’s troops without any fighting.

All in all, classical Chinese and Western rhetoric both played a crucial role in the development of human civilizations. The contention of a hundred schools of thought during the Spring, Autumn and Warring States period constituted a glorious page in the history of Chinese civilization, echoing contemporaneous Ancient Greece and benefiting generation after generation. Rhetoric itself has the common nature of resolving conflicts non-violently, coordinating human actions and influencing human thoughts.

Contemporary role

In the 1960s, Western scholars of such fields as philosophy, linguistics, sociology and psychology began to revisit rhetoric, “intervening” in the ancient discipline successively. Rhetoric also started to incorporate things of diverse natures, absorbing rich theoretical nutrients from different disciplines. While attempting to include all symbolic human behaviors related to meaning in its scope of research, its focus was shifted to meaning and relations between man and society. After thousands of years of ups and downs, Western rhetoric has made significant progress and achieved a transformation.

British rhetorician Ivor Armstrong Richards defined rhetoric as a study on misunderstandings and their remedies. American scholar Richard M. Weaver evaluated the ability of rhetoric to persuade. American literary theorist and critic Kenneth Burke said that rhetoric, which is “rooted in an essential function of language itself,” is the “use of words by human agents to form attitudes or to induce actions in other human agents.” French philosopher Jacques Derrida insisted that without rhetoric and the power of rhetoric, there would have been neither politics nor human society. Stanford professor Andrea Lunsford defined rhetoric as an art and practice for the study of the communication of all humanity.

Chinese rhetoric has gradually fostered a distinctive development path and national characteristics in the course of more than 2,000 years. Although it differs vastly from Western rhetoric due to different values, social backgrounds, customs and religious beliefs, contemporary Chinese rhetoric has broken away from the narrow outlook of “making language artistic” or “adjusting words to the theme and the situation” and instead has created a new research landscape while drawing upon Western rhetoric and carrying forward its own excellent traditions.

For example, Hu Fanzhu, a professor of applied linguistics at East China Normal University, has focused on the analysis of discourse behaviors, stressing the important role of rhetoric in promoting the socialization of individuals, interactivity between groups and modernization of social life. Chen Rudong, a professor from the School of Journalism and Communication at Peking University, emphasized rhetoric as a communicative and social behavior, adding that people construct and understand discourse consciously and purposefully according to specific contexts to achieve ideal communicative effects. Tan Xuechun, a professor from Fujian Normal University, devoted himself to exploring how rhetoric participates in the construction of discourses, texts and subjects.

Chinese and Western rhetoricians in the contemporary era have offered diverse definitions and analyses of rhetoric, but their theories tally with one another to varying degrees. Contemporary rhetoric studies, Chinese and Western, have coincidentally turned to the role of discourse in enhancing interpersonal communication and understanding and that of rhetoric in easing or addressing social contradictions, as well as dealing with social problems.

Contributing to world peace

The present world is turbulent and divided at an unprecedented degree. As some countries attempt to thwart globalization, disagreements in interests and values between countries around the world are increasingly sharp. The world power pattern is changing.

To some extent, to improve national cultural soft power is to enhance the rhetorical ability to persuade and convince others and raise one’s voice in global affairs. When rhetoric is limited to verbal fights, resorting to violence might be unavoidable for part of humanity. However, in this world with nuclear weapons, violence might end up eliminating humanity.

The efforts of rhetoricians might be hopeless against various inhumanities that have been threatening the existence of mankind. Before WWII broke out, Burke wrote a critique of Hitler’s rhetoric, but didn’t draw any attention from American academia, even though the hunch was later verified. In this sense, rhetoric should serve as an effective means to avoid and replace violence. This is where Chinese and Western rhetoric agree with each other in the contemporary age.

Zheng Jun is from the College of Foreign Languages at Fujian Normal University.

edited by CHEN MIRONG