Bashu symbols valuable to building of Chinese semiotics

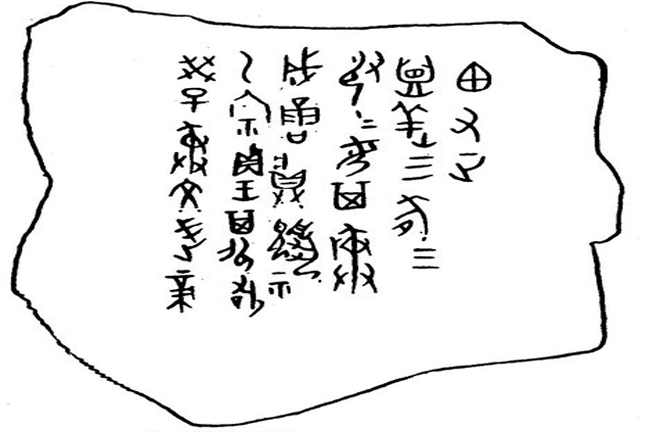

Bashu symbols and graphic characters Photo: FILE

Bashu symbols and graphic characters, also known as Bashu symbols or Bashu characters, are an umbrella term for patterns, inscriptions and seals on bronzeware unearthed from the Sichuan Basin of southwestern China since the 1920s. Bashu symbols are universally acknowledged by academia as a kind of ancient writing, and the only confirmable pre-Qin characters apart from Chinese characters. Many studies in recent years have shown that Bashu symbols are associated with the ancient script of the Yi ethnic group. However Bashu symbols are categorized, their value to the Chinese linguistic and cultural genealogy is self-evident.

Semiotic attributes

From the perspective of semiotic structure, there are many pictographs in Bashu symbols, so they are also called graphic characters. So far 272 types of symbols have been collected, roughly divided into human, animal, plant, utensil, building and geometric shapes. Among others, there are 12 types of human-shaped symbols, 26 of animal patterns, 33 resembling plants, 31 like utensils, and 20 agricultural symbols. However, Bashu symbols are not all hieroglyphic. Quite a few of them are too abstract to identify as pictographs.

Scholars are divided over the phonographic features of Bashu symbols. Qian Yuzhu, a renowned expert on the ancient writing of the Bashu (modern-day Sichuan and Chongqing) area, conjectured from the relationship between Bashu symbols and ancient Yi characters that the graphic symbols might be a kind of alphabetic writing dating to 2,400 years ago. Based on the structure of each character, archaeologist Tong Enzheng argued that the square characters are not alphabetic; they must be ideographic like Chinese characters.

Moreover, the Bashu symbols discovered are mostly single signs without connections or syntactic relations with each other. Since they appear on costly bronzeware, they are likely to be highly symbolic.

Compared with oracle bone inscriptions, Bashu symbols are more graphic. Exemplifying word formation, they can illuminate more dimensions of the evolution of different veins in the Chinese linguistic genealogy. In addition to cultural archaeological results, Bashu symbols are generally considered a product of the cultural community consisting of many related tribes and clans, which makes them an excellent example of semiotic integration. Therefore, Bashu symbols have dual value as a subject of Chinese semiotics.

Imperfect Western semiotics

Ideographic writing represented by Chinese characters has always been subject to prejudice, and even stigmatization, in the West. Hegel contended that alphabetic writing is in and for itself the most intelligent, adding that the “hieroglyphic writing system” of the Chinese is “adequate for the statutes of Chinese intellectual development.” Rousseau said that Chinese characters are advanced only to the most primitive object drawing, while alphabetic writing corresponds to civilized society and order. Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, one of the founders of modern semiology, defined his research scope of linguistic semiology as an alphabetic system with Greek letters as the prototype.

The above prejudices in fact take root in the West-centric “linear Darwinian semiotics,” going against the essence of cultural diversity. From academic and historical angles, linear Darwinian semiotics turns a blind eye to the fundamental truth that the Eastern and Western cultures have existed in two different evolutionary systems. In terms of semiotic form, it is a matter of the difference between hieroglyphic and phonetic civilizations, deeply rooted in their respective cultural beliefs.

In China of the Orient, phonetics is by no means great. Chinese ancestors took it for granted that birds and beasts have their own sound languages. It was characters that endowed human beings with super powers. Legend has it that deities and ghosts cried and the sky rained millet when Cangjie, a mythological figure with four eyes in ancient China who claimed to be an official historian of the Yellow Emperor, invented Chinese characters.

Zhang Yanyuan, a painter and painting theorist in the Tang Dynasty (618–907), explained that with the invention of Chinese characters, Nature was unable to conceal its profound mysteries, and deities and ghosts could no longer hide their movements and expressions. This explanation is also the earliest origin of the theory that Chinese painting and calligraphy are closely related.

This reflects that the impetus of the Chinese writing and semiotic system was grounded upon the creation and evolution of characters. It differs vastly from the alphabet-based Western linguistic semiotic system.

The Saussure semiotic system that discounts motivation is partial in its scope, which has also affected the universal validity of Saussure’s theories. The logical and rhetorical semiotics created by American philosopher and logician Charles Sanders Peirce, the other major founder of modern semiotics, theoretically compensated for the partiality of the former to some extent, but as a “logic science,” it hardly involves any specific cultural objects. As a result, semiotics becomes a formal logic deficient in the interpretation of occasional and specific cultural examples.

How to enrich concrete cultural objects on the premise of universally valid theoretical logic is an important research direction for contemporary semiotics. Currently, the general study of pictures, or pictorial semiotics, which is thriving in Western academia, is an attempt of this kind. Nonetheless, it focuses more on general images in a non-language sense, which results in significant asymmetry between non-language pictorial symbols and language. The research of general images is undoubtedly important, but it can never make up for the absence of motivation and script study in Saussure’s linguistic semiology.

Hence it is necessary to find a systematic, complete and highly motivated sample of cultural symbols. Through a panoramic view of the entire history of human civilization, Chinese language and characters are exemplary. As the motivation of oracle bone inscriptions has been highly systemized through syntactic analysis, the clear motivation of Bashu characters as discrete symbols makes them a perfect complement to oracle bone scripts.

Urgency of semiotic construction

The Ancient Greek tradition of logic has been well inherited by modern Western semiotics. Saussure’s structural symbols and Peirce’s logic and rhetoric are branches of the inheritance.

When it comes to China in the East, however, neither the Book of Changes that is regarded as the first semiotic expression of human experience nor mingxue, the study of names, which discusses names and meanings almost contemporarily with the Stoicism of Ancient Greece, has secured a seat in basic models of current semiotics. Bashu characters and symbols, the subject of this article, are more seriously marginalized in the semiotic system dominated by Western phonetics.

Since modern times in China, with the demise of the feudal Qing Dynasty (1616–1911) and the invasion of foreign powers for more than a century, some intellectuals who were influenced by the Western enlightenment accepted the phonetics-centric prejudice and attributed the backwardness of the nation to culture, putting the blame on characters and symbols and launching Latinization campaigns in attempts to abolish Chinese characters.

With a history of thousands of years, characters and symbols represent the lively culture of the entire Chinese civilization. Eliminating semiotic differences to embrace globalization is by no means an option for a country to develop its culture.

France has persisted in defending and carrying forward the French language for more than 400 years since 1539 when King Francois I promulgated a decree defining French as the official language.

The Chinese character system carries the cultural life of China and distinguishes the nation from the West. Amid information equalization caused by information globalization, cultural identity has become increasingly weak, but characters and linguistic symbols are crucial to the building of cultural identity.

To sum up, constructing a cultural semiotics that accounts for motivation in Chinese characters, including Bashu symbols, is not only conducive to showcasing the cultural achievements of Chinese characters, but also to building a theoretical system of Chinese semiotics different from the Western alphabetic system.

Hu Yirong is a professor from the College of Literature and Journalism at Sichuan University.

edited by CHEN MIRONG