Preconceived notions block innovation in communication studies

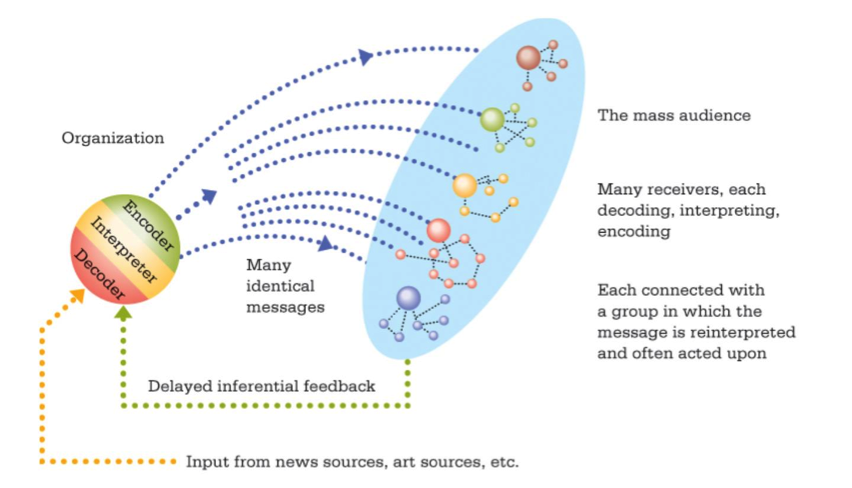

The model of mass communication was proposed in 1954 by Wilber Schramm, a founder of the field of communication studies. According to Schramm’s model, coding and decoding are the two essential processes of an effective communication.

Given that the internationally recognized theoretical basis of communication studies originated from the West, it is wise for scholars to keep in mind the relationship between language and mindset when endeavoring to make advancements in the field with regard to Chinese language.

The distinctive mode of thinking conveyed by Chinese language differs much from other languages, such as English, and this factor, to some extent, decides how basic theory of communication should be studied. It also determines the degree to which relevant research results will be accepted by international academia.

Old ideas form hurdles

What kind of attitude should the academic community hold toward theoretical innovation? How should potential emerging research results be evaluated?

A review of the history of scientific research may provide us with the following answer: old ideas and established theories are often the biggest hurdles on the way to unknown discoveries.

From the perspective of thought patterns, it can be said that the greatest impediment to theoretical progress is the preconceived notions of the scholar himself, which may sound paradoxical, but is a matter of fact. An example of this is the concept of cognitive schema, one of the key ideas of communication theory. A schema is a mental template based on previous experience that a person calls upon when confronted with familiar people and situations.

Whether or not media serves as the intermediate agent, the way in which humans acquire knowledge about the world is confined to their preconceived ideas constructed on the basis of their minds, knowledge and personal experience.

Any seemingly novel and external information, knowledge or theory would intrinsically fall into the framework of the preconceived notion and schema of the receiver (but not the acceptor) due to his or her mindset and emotional prejudices.

For some unknown reason, researchers of the social sciences, especially communication studies, seem to regard themselves as immune to this tendency. But even scholars strictly trained in their specialization have a hard time avoiding it.

It can be said that if academicians evaluate new research in the field of communication theory by the benchmark of extant recognized formulae, especially long-established academic criteria, breakthroughs in theory will become quite rare.

Having realized the trap of a rigid scientific mindset, let us come to the next topic: the law governing the mode of theoretical thought. Many core disciplinary theories develop and evolve in conformity to the law of thesis-antithesis-synthesis, metaphorically as the “destiny of mind.”

Much like the inertia of social evolution or a pendulum swinging from one side to the other, these theories cannot reach a balance in the short term. However, examining the evolving history of the discipline, we may find its own fatal defect: there are hot spots but no frontiers. This is because communication studies, a discipline that mixes the social sciences and humanities, covers a wide range of research subjects. Thus, readers may be puzzled by the following: What is the cutting-edge knowledge of the discipline? And who is eligible to be recognized as the authority in regards to the frontiers of the discipline?

In fact, since scholars of communication aim to study the most prevailing social phenomena, they definitely do not need to blindly follow or succumb to a particular authority, fanatically holding the so-called cutting-edge theories in high esteem. Otherwise, it would be like bartering the trunk for the branch if we mistakenly consider each emerging media technology far-reaching enough to be the frontier of communication study.

Academic research, more an art than a craft

Given the fast pace of change in today’s society, in which technology reigns supreme, the only “constant” that scholars of communication are able to grasp is people. The subject of communication is people, so is the real channel, the participant and receiver of it. That is why disciplines from literature, art to education share the same target of communication: a dedication to meeting the common, deep psychological demand of mankind’s inner self.

So, where is the point of departure for the research to be conducted? Here, methodology is involved. The prerequisite for a methodology to gain universal acceptance is feasibility. That is why a great many topics and hypotheses of research have failed to produce fruits—it is infeasible to conduct research and test them by adopting the extant methodologies.

In my book A Talk of Personal Experience: New Exploration on Communication Theory, I propose the idea that many theoretical propositions derive from empirical study and that the former complement rather than subvert the latter. But perhaps it is also possible that certain theories are so strongly persuasive that no scientific evaluation is needed. All these are closely related to the mindset involved in scholarship, which is actually not that notable, except that it is characterized by logic, clarity and rigor.

On the contrary, the social phenomena of communication, which are the subjects of research, tend to be illogical and incoherent to a degree that usually exceeds scholars’ expectations. So should we seek commonality through diversity or vise versa?

To many natural scientists, even Nobel Prize laureates, real academic research is more an art than a craft. Therefore, the methodology involved in communication theory should not blindly pursue the craft while forsaking the art, though it is admitted that craft is important for academic training.

Great theory provokes thought

The direct purpose of communication studies in the academic sense is to develop more classic theories and knowledge for the discipline. An example is the empirical school of communication. Many of its important theories, such as the theories of gatekeeping, framing, and agenda-setting are derived from metaphorical use and are constantly being verified.

But what criteria should be used to judge whether a theory is classic or not? Here, the state of mind regarding scholarship is essential. What is scholarship in its ultimate sense? Where is scholarship heading if it is to achieve a higher aim?

The theory of effect, which holds an unparalleled position in mainstream communication theory, can be used to explain how scholars will respond to new and old concepts.

One pair of effects is establishment and absorption. Most of the established communication theories are regarded as landmarks in the field. However, by looking only to the landmarks set by predecessors, younger scholars can be blinded to theoretical innovation.

Another group of effects is cultivation and influence. Cultivation theory, one of the important theories of communication, aims to examine the long-term cultivated negative effects of a certain type of medium, particularly television on its viewers. But “influence” looks at positive effects of communication, which has the potential to be applied to contemporary social realities.

There are also dynamic and static effects. Excited or touching emotions cannot last long, so this is a dynamic effect, which, if durable, could be considered static.

Then there are reserved and unconstrained effects. The receivers may feel constrained by some information during the process of transmission because a pre-existing schema may bias their minds. But some other valuable information can open receivers’ minds with an affirmative effect, which can nevertheless be temporary, and the scholars may soon shun the new ideas because it is hard to evaluate such effects empirically.

Each new theory and idea could possibly emerge as a response or in opposition to existing ones, which in academic terms is called “criticism” or “critique.” Scholarship, in a real sense, ought to provoke thought and inspire imagination.

However, just as the most euphoric music cannot sometimes overcome the discord in people’s minds, a truly great theory may not necessarily win over scholars despite their prejudices. Nonetheless, it can be capable of overshadowing many of the old theories. The point of departure for theoretical innovation, undoubtedly, is to emancipate the mind and thought.

Chen Yanru is from the School of Journalism and Communication at Xiamen University.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No.662, October 30, 2014.

Edited and translated by Bai Le

Revised by Justin Ward