Rise of China-Chic in traditional opera inspires contemporary fashion

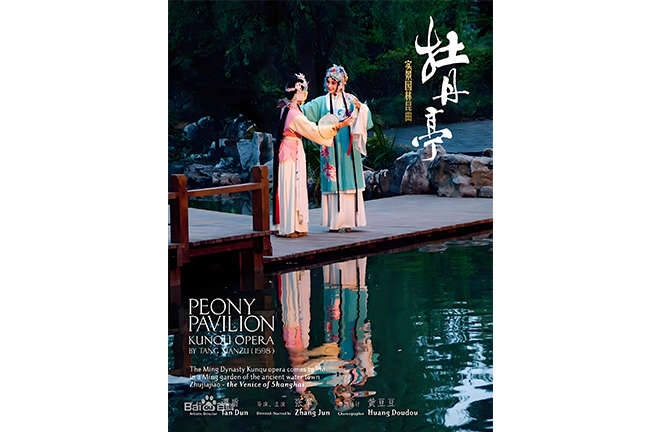

FILE PHOTO: The Kunqu opera, Peony Pavilion, performed in a century old garden in Zhujiajiao, a water town in the suburbs of Shanghai, bringing the audience a unique, contemporary sensory experience

The emergence of cultural trends is closely tied to the spirit of the times, and the rise of China-Chic-infused opera vividly reflects this phenomenon. From changes in performance forms and content creation to new modes of dissemination, this movement has driven the deep integration of traditional culture with modern aesthetics. In recent years, China-Chic-infused opera has quietly gained momentum, gradually becoming a prominent trend.

Born from cultural confidence

Trends, as social and cultural phenomena, reflect the spirit of the times and the aesthetic preferences of particular historical moments. Looking at the evolution of global trends, each era has produced influential cultural waves: in the 1970s, the hip-hop movement emerged from American street culture and swept across the globe; in the 1980s, Japanese anime culture gave rise to the “otaku” phenomenon; in the 1990s, South Korean idol groups ignited the “Korean-wave” (Hallyu) across Asia.

With China’s rapid economic ascent and growing national strength, cultural confidence and national identity have steadily deepened. In the early 21st century, the homegrown cultural trend now known as “China-Chic” began to take shape. In sectors such as fashion, cuisine, and cultural innovation, domestic brands that combine traditional Chinese elements with modern sensibilities flourished, giving rise to a robust China-Chic movement. This trend has ushered many traditional art forms into a new era of openness and diversity—and traditional Chinese opera has become part of this cultural resurgence, giving rise to the phenomenon of China-Chic-infused opera.

Admittedly, the term “China-Chic-infused opera” has yet to be clearly defined in academic discourse. It is better understood as a descriptive label for the phenomenon in which traditional Chinese opera seeks to strike a balance between inheritance and innovation in the contemporary era. It highlights the genre’s capacity for reinvention and adaptability, revealing a seamless fusion of classical elegance and modern flair.

Traditional opera coexists with fashion trends

When traditional culture is reimagined in ways that resonate with younger audiences, it can once again emerge as a cultural trendsetter. In 2004, the youth edition of Peony Pavilion—a celebrated Kunqu opera [which originated in the 14th century in Jiangsu Province’s Kunshan region and served as a foundation for many other regional operatic styles]—made a successful debut, sparking a resurgence of enthusiasm for Kunqu. It marked the genre’s most significant revival since the 1956 classic Fifteen Strings of Cash [an adaptation by the Zhejiang Kunqu Opera Troupe], which was once credited with “saving a dying genre.” This production is widely regarded as the opening act of what is now known as the China-Chic-infused opera movement.

How can a 600-year-old genre and a play written over four centuries ago appear “youthful” once more? From its youthful cast and innovative performance styles to its fashion-forward stage design and multifaceted promotional strategies, the youth edition of Peony Pavilion succeeded in drawing large numbers of young theatergoers. According to available data, since its premiere in 2004, the production has been staged over 500 times in more than 60 cities and 40 universities both in China and abroad, reaching a total audience of more than 800,000, with the average age of theatregoers reportedly dropping by 30 years.

Building on this success, other opera forms—such as Peking Opera, Yue Opera [which originated in Zhejiang Province in the early 20th century and is often described as the most tender and romantic of Chinese operatic styles], and Huangmei Opera [from the Anhui region, known for its lyrical melodies and expressive performance techniques]—have also explored youthful reinterpretations of classical works. Productions like the National Peking Opera Company’s youth edition of The Female Generals of the Yang Family, the Zhejiang Xiaobaihua Yue Opera Troupe’s The Five Daughters Pay Their Respects, the Anhui Huangmei Opera Theatre’s The Female Prince Consort, and the Zhejiang Wu Opera Troupe’s Mu Guiying have not only captivated a broad spectrum of younger audiences but also sparked lively discussions among performers and scholars alike.

Rise of immersive experiences in traditional opera

The concept of immersive art can be traced back to the 19th century, when artists began experimenting with experiential forms to transcend the limitations of traditional Western painting. In 1968, American theater theorist Richard Schechner introduced the idea of “Environmental Theatre.” Later, the rise of immersive drama in the UK broke the conventions of fixed-stage performances by eliminating fixed seating and offering audiences greater freedom and engagement.

In traditional Chinese opera, the creation of immersive experiences has now become a clear trend. In 2010, Peony Pavilion was staged in a classical garden setting through a collaboration between the renowned composer Tan Dun and top-class Kunqu opera singer Zhang Jun, pioneering the immersive presentation of Kunqu opera. Since then, local troupes have continued to produce distinctive immersive performances. Audiences often report that these productions transform them from passive observers into active participants, leaving a strong and memorable sensory impression.

Offline immersive opera relies heavily on imaginative spatial design, while digital immersive opera breaks through the “fourth wall” of traditional staging. As digital technologies become more prevalent, opera companies are increasingly adopting intelligent digital stages that incorporate VR/AR and holographic projection to craft novel audience experiences. For example, the Peking Opera production Concubine Mei used 6DoF technology to present a 360-degree jinghong dance, while Peony Pavilion employed holograms to create a dreamlike visual atmosphere. In the future, such digital innovations may well become standard practice in Chinese opera.

The China-Chic-infused opera trend is not only transforming the performing arts—it is also extending into broader cultural and creative industries. In fashion, traditional Peking Opera elements have been seamlessly incorporated into modern clothing design, even appearing on runways at Paris Fashion Week to showcase the essence of Chinese culture to a global audience. In pop music, songs such as The Drunken Concubine, which blend contemporary styles with traditional opera vocals, have gained traction and expanded opera’s appeal. In the gaming world, mobile games like Justice Online and Genshin Impact have skillfully embedded Chinese opera elements, deepening their cultural resonance and highlighting the wide-ranging applicability of opera aesthetics.

Breaking boundaries while protecting the core

In the age of new media, Chinese opera has evolved from a one-way broadcast medium into an interactive form of communication, thanks to social media and short video platforms. This transformation has lowered the barrier between traditional opera circles and the general public, making the art form more accessible to young audiences and encouraging broader participation in both its appreciation and dissemination.

For instance, the “Shanghai Theatre Academy Girl Group 416,” made up of five Gen Z Peking Opera students—mainly roommates from dormitory 416—gained popularity by live-streaming opera-infused songs frequently appearing on trending charts across social platforms. Renowned Peking Opera artist Wang Peiyu attracted an audience of 20 million by creatively demonstrating traditional laosheng (old male role) vocal techniques through interactive livestreams. A 66-year-old Huangmei Opera troupe gained nearly 600,000 followers on Douyin (Chinese version of TikTok) within just three months after launching their account. During the 2024 Dragon Boat Festival, Douyin partnered with eight state-owned opera troupes to present a “Top Troupes of China” livestream week celebrating intangible cultural heritage, showcasing 70 classic plays and drawing more than 64.2 million online viewers.

These examples show how short video platforms have become crucial channels for the promotion of Chinese opera. Still, caution is warranted against over-reliance on new media. In today’s landscape of fragmented information, while short videos can reach wide audiences, reducing long-form content to superficial clips, recycling outdated material, or resorting to vulgarity for the sake of clicks risks diluting opera’s unique appeal in a crowded digital space.

The current rise of China-Chic-infused opera should be guided by a careful balance of tradition and innovation. While youthful aesthetics, immersive staging, and digital adaptations can capture attention, they may not, on their own, satisfy the increasingly refined tastes of contemporary audiences in the long run. Creators should engage deeply with the artistic core of Chinese opera—preserving tradition without being constrained by it, and honoring classical heritage without merely replicating it. By developing creative approaches that speak to present-day sensibilities, opera can continue to express its enduring humanistic spirit.

Guo Kejian (professor and dean) and Li Luxingyu (contract research fellow) are from Shi Guangnan Music and Culture Research Institute at Zhejiang Normal University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG