Lyu Simian’s historical narratives: A fusion of scholarly rigor and accessibility

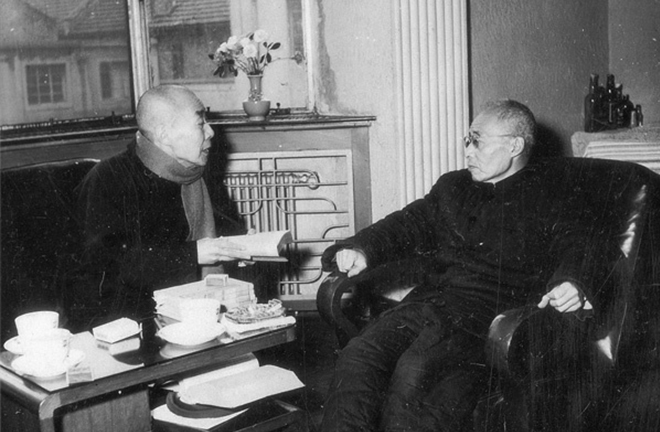

FILE PHOTO: Lyu Simian (left) and Meng Xiancheng (right), the first president of East China Normal University

In Historical Research Method, Lyu Simian observed that one of the shortcomings of traditional historiography lies in its “emphasis on political narrative.” While acknowledging the historical reasons for this focus, Lyu contended that modern historians should strive to improve upon such conventions. Lyu’s extensive body of work covers a wide range of topics, making it difficult to summarize concisely. Nevertheless, his historical writings can be broadly categorized as follows: for ancient history, his focus centers on people’s livelihood; for modern history, he emphasizes culture and reform; and in his popular historical writings, he is primarily concerned with drawing practical lessons from the past.

People’s livelihood in ancient history

Lyu’s general and periodized histories are consistently divided into two volumes: one recounting political history over a continuous period or specific era, the other devoted to thematic or topical histories. In addition to discussing government institutions, elections, military systems, religion, and scholarship, these topical volumes devote significant attention to issues such as property, taxation, relief loans, grain trade, storage, canal transport, productive enterprises, currency, daily necessities, and burial customs.

It is for this reason that Yan Gengwang remarked on Lyu’s considerable focus on the social and economic dimensions of history. Yet rather than simply emphasizing socio-economic factors, it would be more precise to say that Lyu centered his analysis on people’s livelihood. For Lyu, the foundation of any nation is its people, and the primary concern of the people is their means of livelihood. Consequently, nearly one-third of his writings address issues directly impacting people’s daily lives.

In order to emphasize livelihood, it is essential to depict the actual living conditions of the populace. For example, regarding the Han Dynasty’s policy of “recuperation and growth,” many historians highlight the state’s policy of light taxation, often citing the “collection of 1/30 of the land’s yield as land tax” to suggest minimal tax burdens. Lyu, however, examined taxation from the perspective of ordinary people: Prior to the Han era, there was no private rent (i.e., rent paid by tenant farmers to landlords), whereas under the Han, in addition to official taxes, farmers also faced private rents. Thus, even though the state levied light taxes, the overall burden on farmers did not decrease—in fact, it increased.

Similarly, in discussing the reign of Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty, many historians cite The Old Book of Tang, which describes how the entire nation experienced bountiful harvests, displaced migrants returned to their hometowns, and rice sold at low prices. Crime rates were low—only 29 people were sentenced to death that year. People did not lock their doors, and travelers did not need to carry food, as they could rely on provisions from strangers.

However, an alternative depiction from The Old Book of Tang is often neglected, which records: “In the Guanzhong and Hewai regions, a large number of military units were established, and wealthy families as well as physically strong men were conscripted into the army. At the same time, due to the construction of the Jiucheng Palace, almost all remaining labor was requisitioned. Society had just undergone turmoil, and the population was already sparse with weak family structures. Once a family member was conscripted, the entire household‘s production and livelihood would fall into hardship.”

Lyu also offered penetrating analyses of ancient China’s monetary systems, stating: “Throughout history, periods of currency disorder outnumbered periods of stability. From the Han to the Song Dynasty, only the Han wuzhu coin and the Tang kaiyuan coin were truly welcomed by the public. Other currencies were merely makeshift solutions. Even during the circulation of these two types of coins, there were still counterfeit and inferior coins mixed in.” Historians often analyze monetary policy through its institutional frameworks and economic impacts while neglecting its direct effects on the livelihood of ordinary people. Lyu’s approach is a valuable model for future historians.

Culture in modern historical writings

Lyu also wrote extensively on modern history, with representative works including Lectures on Modern Chinese History, Introduction to Early Modern Chinese History, and An Overview of China’s Past Hundred Years. In these, his emphasis is on culture and its transformations.

Lyu stated: “Human actions that control the environment constitute culture. Different environments naturally require different control methods, leading to different cultures. The environment is never static; when it changes, people’s methods of controlling it must change. However, cultural transformation lags behind environmental change. The quality of a culture is determined by its ability to adapt to environmental shifts and by the speed at which these adaptations occur.” This dynamic, he argued, is responsible for the rise and fall of nations.

Building on this premise, Lyu observed: “From the Qin Dynasty to the present, over two thousand years have passed, yet China’s territorial boundaries have remained largely unchanged, and its political structures have seen no fundamental transformation. However, with the arrival of Europeans, the entire landscape changed. Their culture was vastly different from ours, and their military and political power far surpassed that of previous foreign invaders. As a result, China underwent changes in nearly every aspect of life. This is the period we call modern history.”

Following this logic, Lyu identified three major questions in modern history: (1) What environmental changes did China experience in modern times? (2) What was the state of Chinese culture when it entered modernity? (3) Did the environmental changes spur cultural reforms, and if so, how did they unfold? These themes form the core of his modern historical narratives.

Lyu illustrated these cultural transformations through historical events and figures. Some clung to outdated perspectives in confronting new challenges. Others emerged as pioneers of cultural reform, including Kang Youwei, who assumed a leading role in the reform movement in 1898, and Sun Yat-sen, a leader of the 1911 Revolution. Cultural reform thus emerges as the dominant theme of Lyu’s modern histories.

Given the differing pace and scale of these changes, Lyu divided China’s modern history into two phases: (1) the period of foreign coercion, from the arrival of Europeans to the late Qing era, characterized by foreign powers competing to carve out spheres of influence; (2) the period of Chinese resistance, beginning with the 1898 reforms. He emphasized that cultural change is essential for vitality: “Cultural upheavals inevitably involve sacrifice and suffering. The greater the resistance to new culture, the more severe the suffering.” Hence, he urged overcoming cultural inertia, cautioning against the danger of being “too fond of conservatism and too fearful of reform.” Lyu’s modern historical writings, as Zhao Qingyun noted, stand out in academic history for their focus on culture and its evolution.

Emphasizing lessons from history

Lyu also authored numerous popular historical works and opinion pieces for the general public, distinct in style and approach from his academic writings.

While popular historical writing is often seen as entertainment, Lyu rejected this as its primary aim. Rather, he believed compelling events and figures should serve as vehicles for conveying historical principles. He argued that these principles “should be understandable to everyone,” making complex scholarship accessible to all.

For example, in Three Kingdoms Historical Talks, he discussed Guan Yu’s loss of Jingzhou [Guan Yu lost Jingzhou in 219 CE due to overextension in his northern campaign against Cao Cao. While besieging Fancheng, Sun Quan launched a surprise attack on Jingzhou. With his supply lines cut, Guan Yu was forced to retreat but was captured and executed. This loss weakened the reign of Shu Han, led to Liu Bei’s failed revenge campaign, and solidified Sun Quan’s control over the region]: “Guan Yu was undoubtedly talented; his failure should not diminish our respect for him. On the surface, his arrogance and overzealous ambition were the immediate causes of his downfall, but a deeper analysis reveals that Liu Bei’s eagerness to conquer Liu Zhang was the true underlying factor.” Liu used this event to illustrate the broader lesson of how excessive scheming may lead to failure: “Being overly scheming can sometimes lead to failure… It’s better to rely on righteousness and act accordingly in all things.”

Lyu opposed vague exhortations to “learn from history,” arguing that historical events are ever-changing. Relying on past experiences to address present issues risks “using outdated remedies for new ailments.” In the 1940s, amid debates over relocating China’s capital, scholars often cited historical principles of site selection. In response, Lyu wrote an article titled Why Nanjing Became the Capital of the Six Dynasties and the Ming Dynasty, in which he argued that past discussions on capital locations were based on conditions where land transport relied on horse, water transport depended on sails, and wars were fought with spears and bows. However, with the advent of steamships, trains, airplanes, motor vehicles, and telecommunications, the geographical advantages of the past had been fundamentally upended. Therefore, discussions on capital relocation and construction today should not be constrained by historical perspectives alone.

The world’s complexity renders some past lessons obsolete as social conditions evolve. However, when circumstances persist over centuries, historical insights can still be valuable references. In his article, Lyu pointed out that ancient governance placed great emphasis on fenghua—the moral and social order. The national capital was traditionally regarded as the beacon of virtue, and its selection and construction could not disregard this aspect. He believed that these ancient reflections on social order in capital governance merit serious consideration by historians today.

Zhang Genghua is a professor from the Department of History at East China Normal University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG