Reflections on Zhao Tingyang’s post-human world assumptions

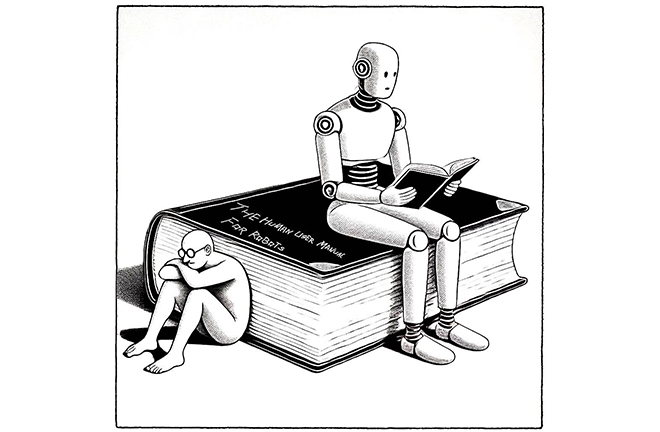

“New Tools” drawn by Wang Xiaowei

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) technology has facilitated the emergence of a more comprehensive and systematic phase of automation across virtually all domains of human life. With the aid of tireless computational systems and an array of robotic agents, production efficiency is poised to increase significantly. In a simplified and idealized scenario, such technological progress could potentially make the principle of “to each according to his needs” a tangible reality. Yet, the pressing question remains: how will humanity reinvent itself within this specific material context?

Idealized future world

Renowned Chinese philosopher Zhao Tingyang’s exploration of the concept of post-humans is likely situated within an idealized vision of a future world. From the standpoint of an average individual, I also presuppose certain baseline conditions for such a world: there is no requirement for one to serve as a moral exemplar. One need not be a saint or a hero, and neither should one be a psychopath. Rather, the individual occupies a median position, existing primarily as oneself in most circumstances.

I contend that human nature is not inherently malicious and can, at times, be quite endearing. This perspective does not negate the fact that I have encountered individuals who are profoundly despicable, but rather reflects an average or general perception of human nature. Zhao, however, presents an alternative view. He posits that if human nature is viewed as a constant, its essence would likely be characterized as “a tendency towards indulgence and laziness.” In the context of advanced technological development, this aspect of human nature would inevitably lead individuals to externalize all cognitive and intellectual burdens, delegating them entirely to machines. Meanwhile, they would reserve the material benefits for themselves, providing machines with only minimal resources, such as electricity, in return. From this perspective, the post-human condition would be defined by a bored and disengaged populace, epitomizing mediocrity.

However, human nature is shaped by its temporal context. It is challenging to conceive that Homo sapiens from eastern Africa over 100,000 years ago would possess the same personality traits as your neighbors today, even though there are no fundamental biological differences between them. At the very least, modern humans appear far more peaceful—we generally no longer resort to cannibalism. This suggests that human nature may not be a constant, but rather a variable, one that exhibits characteristics of level-two chaos [discussed by Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind]. How we perceive human nature can influence its trajectory, much like how the way we raise children shapes their development. I am inclined to believe in the openness of human nature and feel a responsibility to interpret humanity in a more optimistic light.

A plausible conclusion is that human nature is not a constant; it is not inherently characterized by indulgence or laziness. At most, humans may have a propensity for such traits, but achieving them could ultimately lead to suffering instead. Human nature possesses resilience, engaging in a constant tug-of-war with new technologies. As social constructivists have observed, humans shape technologies to align with their values and needs, while phenomenologists of technology note how technologies deeply influence human subjectivity, pushing people to adapt to their demands.

The specifics of what post-human existence might look like elude my imagination. The pace of technological advancement is so rapid that individuals are ill-equipped to systematically categorize potential future technologies. Particularly when constrained by disciplinary boundaries, it is difficult to critically examine technology from the perspectives of corporations, scientists, or governments, thus preventing the formation of a holistic conceptualization. Nonetheless, one might speculate—albeit crudely—that if both human reason and physical labor are replaced by machines, humanity might suddenly encounter a profound philosophical opportunity. If machines surpass us in intelligence, excel at generating scientific knowledge, and prove more effective than us as causal agents in shaping outcomes in the world, what remains of human existence? And can these remnants provide enough meaning for us to live with peace of mind?

Aversion to life

Zhao offers an insightful perspective on a potential trajectory for post-human existence. He argues that, from tradition to modernity, humanity has shifted from a collective orientation to an increasingly individualistic one. Modern individuals, he contends, possess an exaggerated sense of self. Zhao views this development with skepticism, observing that modernity often brings a profound lack of meaning, manifesting not as suffering tied to specific events but as an existential malaise—a discontent with life itself. In other words, modern individuals harbor a deep aversion to life.

I fully agree with this assessment, and this phenomenon is strikingly evident in various online discussions, where some individuals display an apathy toward every aspect of life. It is difficult to attribute this widespread aversion solely to an inflated sense of self, as its origins are manifold and complex. However, one discernable pattern emerges: contemporary individuals have lost reverence for tradition, affection for others, and the ability to envision a future. Within this world, an immense self kneels, perpetually confronted by nihilism. I am uncertain about what role AI might occupy within such a spiritual landscape. Will it assume the role of an “other”? Can we cultivate affection for it? Or will it remain an insignificant, external clamor, separated from our spiritual lives?

Struggles in life often drive individuals toward fantasy. Zhao distinguishes between two types of fantasies. The first is classical and spiritual, exemplified by Greek tragedy. The second is psychological, encompassing phenomena such as wish-fulfillment fiction and trivial short videos. In the technological age, the fantasies of contemporary life are not spiritual but physiological. For some, escaping from life means dissolving the self in streams of videos or consumption, numbing oneself with alcohol or online literature before the realities of life intrude again. This has become a way of life for many, a routine we all share to varying degrees. Purely physiological fantasies are notably effective in suppressing destructive impulses toward the world. However, the issue lies in the fact that fantasies, especially technological ones—such as various virtual worlds—introduce a new metaphysics that persuades people to perceive the virtual as real. In comparison, the present world of everyday life seems overly monotonous. Offline, life is full of resistance; online, it flows freely. From the perspective of this new virtual realm, the established meanings of the old world appear stale, while the possibilities and ambiguities of the new world elicit great anticipation, with almost revolutionary potential.

I fully align with Zhao’s position that humans need fantasies. While fantasies may not constitute the most solid foundation of life, they represent its lightest and most uplifting elements. I also concur with his distinction between the two types of fantasies and acknowledge that the density and intensity of physiological fantasies, facilitated by contemporary technology, now far surpass those of spiritual fantasies. In the present, many individuals still operate within a classical mental framework, maintaining a sense of reverence for stability, boundaries, and order. Many were born prior to the advent of the internet and mobile phones, when technology had not yet become an integral part of daily life. However, there are also numerous individuals who were born into a high-tech environment, with their identities and personalities shaped in tandem with the internet, AI, and other technological advances. For them, the classical paradigm appears rigid and is often seen as something to be challenged or overcome through the application of new technologies. At the same time, some individuals who have faced significant struggles in life turn to physiological fantasies as a way to cope, yearning for and defending them as a form of protest against the harshness of reality. Among this group, a small segment (ideally) engages in an intense immersion in wish-fulfillment literature, sometimes coupled with a rational critique of it. This dynamic reveals a profound antagonism toward life itself.

Reason in daily life

Zhao expresses a concern regarding the world shaped by advanced technologies, fearing that material advancement and the concomitant decline of the spiritual are mutually reinforcing phenomena. He contends that as traditional frameworks lose their ability to offer the necessary resistance, the post-human world may succumb to a new form of religion, plunging humanity back into obscurantism. To counter this risk, Zhao appeals to reason, reflecting an Enlightenment-inspired stance common among intellectuals in the public sphere during the 1980s and 1990s. To adopt such a tone today would require a certain degree of intellectual heroism. In online discourse, intellectuals who invoke reason often seek to assert their position from a standpoint of authority; however, in today’s digital landscape, doing so can be fraught with risks, as it is safer to engage in dialogue from a lower stance, lest one become the target of mass ridicule.

Reason is undoubtedly a lofty and even supreme ideal, but it is evident that not everyone is capable of embracing it fully. I remain uncertain as to whether reason alone can effectively counteract the physiological fantasies of the technological age or remedy the widespread disdain for life itself. A fundamental reality is that even if all individuals possess reason, not all would be inclined to exercise it. Instances of reason being relegated to the status of a vestigial appendage are not uncommon. Furthermore, the application of reason is an inherently energy-intensive process. When one is immersed in arduous, labor-intensive work, it becomes exceedingly difficult for them to summon the mental energy required for rational thought. In such cases, it is challenging to place blame on their circumstances. Based on my personal experiences and limited observations of others, I contend that returning to the quotidian, as a means of countering the allure of physiological fantasies, may be worth exploring. By “quotidian,” I refer to those bodily, relational, and regularly performed tasks that constitute the fabric of daily life. These activities typically lie outside of systemic frameworks and remain largely insulated from technological influence. Examples include tending a potted mint plant on a balcony, daily school runs, or sitting still in the forest for 10 minutes. These seemingly ordinary activities demand sustained bodily engagement, while the mind is not preoccupied with any utilitarian purpose nor subject to self-monitoring. In the course of everyday life, we focus without specific intent on others and external objects, and in doing so, we derive a form of healing.

I envisage that, in a future where rational capacities are entirely supplanted by AI, as long as people continue to water their plants, remain devoted to their children, and seek solace observing playful tree shadows in the forest, such “post-humans,” despite forgetting basic mathematical truths or lacking any pronounced career ambitions, might still lead a dignified life. Unentangled by physiological fantasies, their spiritual world, while perhaps devoid of tragedy, would retain a form of sensibility.

Wang Xiaowei is an associate professor from the School of Philosophy at Renmin University of China.

Edited by REN GUANHONG