Post-human world and fantasies of new human beings

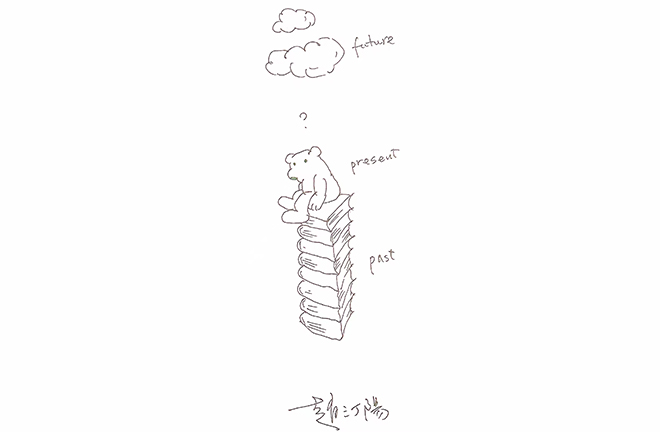

“Time” drawn by Zhao Tingyang

We are said to be living in the “Anthropocene,” an era where human influence has reached a “geological scale,” fundamentally altering the nature of nature itself. It is widely believed that such changes are catastrophic, leading to severe ecological and environmental crises. Yet, even if humans had refrained from altering nature and adhered to a purely natural way of life, it is doubtful this would have resulted in a desirable existence. Until the end of the 18th century, nature was largely undisturbed. During this period, the global population was only approximately 900 million, under very low standards of living. For the majority, material improvements to life were achieved through the exploitation of nature. However, this “good life” is inherently unsustainable. Inevitably, natural or man-made disasters would arise, potentially leading to human extinction. This suggests that the “Anthropocene,” where humanity assumes mastery over nature, paradoxically carries the seeds of an anti-human destiny—unless humanity develops a new civilization capable of safeguarding nature while ensuring human prosperity. For now, this remains an unresolved paradox with no clear solution in sight.

Possible degeneration of humanity

The evolution into “post-humans” may not be good news. Karl Marx’s theory of “digging one’s own grave” can be interpreted as a broad prophecy: any civilization that violates the natural order or disrupts the balance of nature will ultimately seal its own demise. This suggests that humanity cannot ultimately prevail over nature. While the inevitability of this prophecy cannot be proven, reality seems to align with it. The essence of anything labeled “post-x” lies in self-deconstruction and self-alienation. Take postmodernism as an example. Once fashionable in thought, lifestyle, and art, it ultimately lacked creativity and the capacity for construction. Instead of ushering in a new epoch “after modernity,” postmodernism became an exercise in self-deconstruction and self-doubt within modernity.

Fundamentally, postmodernism remains a part of modernity. Despite its dissatisfaction with modernity, it lacks the ability to transcend it. As a result, it is confined within modernity, trying to deconstruct it from within. One could argue that postmodernism represents modernity’s way of digging its own grave, offering only deconstruction without any constructive alternative. If the year 1968 is taken as the starting point of postmodernism, the movement became outdated in mere three decades. Similarly, it seems unlikely that “post-humans” will escape the fate of self-decline or self-withering that plagues the “post-x” concept. Rather than emerging as the long-awaited “new humans,” post-humans may merely represent a regressive form of modern humanity.

Post-humans

The concept of “post-human” is novel and trendy, but there seems to be no consensus on its meaning—only speculation, as post-humans are not yet a reality. One widely accepted view is that the material foundation for post-human existence includes advanced technologies such as AI, genetic engineering, and “inexhaustible” new energy sources. While these technologies offer unprecedented control over nature, they will inevitably also be tools for controlling humanity. Scholars in the humanities often view high technology with fear, offering ethical critiques as though humans are the embodiment and guardians of morality, while AI is cast as a looming threat.

Yet, with a bit of reflection, it becomes clear that all the wrongs in history were perpetrated by humans, the creatures with the lowest moral standards among living beings. The “selfishness” of animals is limited to the struggle for survival, while humans, driven by fabricated values and insatiable desires, are capable of boundless transgressions. In contrast, AI has no intrinsic values or desires. The only “desire” AI might have is the need for a power supply. As long as its energy is secured, AI has no reason to cause harm unless programmed to do so by humans. Thus, any potential danger from AI originates not from the technology itself but from human nature.

Whether an AI-dominated world would be a good one is uncertain. Although the future is unpredictable, one constant remains: human nature. Without significant genetic changes, human nature is unlikely to undergo fundamental transformation and can therefore be treated as a fixed parameter. If human nature is constant, then the high-tech service systems supported by AI, biotechnology, and infinite energy are highly likely to spoil humanity. This vision aligns with Liu Cixin’s depiction of post-humans in his short story Taking Care of God. I am inclined to believe this scenario is the most plausible future. When AI takes over most human labor, biotechnology eliminates the majority of diseases, and infinite energy provides nearly unlimited material abundance, humans—spoiled by these advancements—are likely to experience intellectual decline, possibly even becoming “useless.” As Liu imagined, the majority may not even be able to solve simple “quadratic equations.” However, significant physical decline is unlikely. Freed from the need to earn a living, many will engage in sports during their leisure time, but few will dedicate themselves to intellectual pursuits. Intellectual work is the most taxing form of labor, and aside from geniuses driven by innate intellectual impulses, most people only engage in it out of necessity. An experienced doctor once assured me that human nature is fundamentally indulgent and lazy—a claim I find difficult to dispute. Whether post-humans in a post-human world will live happily ever after remains unknown. However, if human nature persists as a constant, post-humans are likely to represent a regressed form of humanity. Can degraded humans truly be considered a “new” species?

Dream of new human beings

Since the dawn of civilization, humanity has been engaged in reflexive self-imagination. Dissatisfied with their own nature, humans have continually speculated on what they “should” become and have sought to create “new humans.” In this sense, civilization itself is a form of self-design reshaping humanity and human life. Clearly, the concept of “human” is not a fixed, a priori definition but one that is ever evolving, carrying an inherent sense of the future. Across millennia, the role models humans have envisioned fall within the realm of the “new human.” The new human represents an ideal individual, embodying rare but aspirational virtues such as kindness, justice, sincerity, wisdom, courage, responsibility, and selflessness. In traditional terms, this ideal is a composite of truth, goodness, and beauty. However, in the contemporary era, the concept of the ideal human has shifted in its hierarchy of values. Individualistic traits—such as independence, self-assertion, self-realization, individuality, freedom, and equality—are now often regarded as more significant than the classical ideals of truth, goodness, and beauty. It can be argued that contemporary values have become a matter of personal choice rather than adherence to universal standards. Michael Sandel’s discussion provides a pertinent example: a deaf couple who believe that deafness is not a disability but a unique and superior form of value. This case exemplifies how modern interpretations of value have become functions of individual choice.

The shift from ancient to modern values reflects a transition from collective archetypes to individual self-imagination as the basis for personal identity. Individuals now define themselves autonomously, without requiring validation from external social relationships. This ontological evolution has made personal values increasingly anti-social and, in some cases, even anti-biological, as they are elevated above both social and natural constraints. By comparison to their ancestors, modern humans can indeed be described as “new humans.” However, as AI evolves into autonomous entities, humans may transition into “post-humans,” dependent on and “supported” by high-tech service systems.

Fantasies and post-human world

AI and other advanced technologies are poised to create a post-human world. Yet, the nature of this world will be shaped by the choices made by post-humans, suggesting an interactive relationship. Here I am willing to retain some revolutionary hope for humanity—perhaps there is still room for creative renewal. Rationally speaking, however, the likelihood of human degeneration seems greater than that of revolutionary self-renewal. This pessimistic view stems primarily from humanity’s entrenched dependence on superficial pleasures and fantasies, a state that leaves little room for reflection on suffering and the human spirit. Immersed in illusions, people increasingly avoid confronting the fundamental challenges of life, which renders revolutionary self-renewal almost impossible.

Fantasies have existed throughout human history, originally rooted in spiritual aspirations. Over time, however, they have evolved into a product of simplistic pleasures. Modern technological advancements have indeed reduced suffering and increased pleasure, but have done little to enhance genuine happiness. Pleasure today is often derived from fantasies. It is worth pondering why humans require and believe in fantasies—and why they feel compelled to rely on them even if they do not believe in them.

In ancient times, fantasies aimed to construct a certain transcendent spirit for life. In contrast, the modern fantasy is psychological, set to meet psychological needs. Myths, epics, and legends often centered on themes of fate and suffering, seeking to endow life with meaning through miracles, hope, sacrifice, and salvation. These stories encouraged people to confront suffering courageously from within life itself through noble action, rather than fleeing from it. In this sense, ancient fantasies were works of deep thought, even metaphysical explorations.

In contrast, contemporary fantasies often seek to evade life’s challenges by constructing narratives that are more entertaining than the real world. At their core, these fantasies reflect a loss of interest in reality and life. Contemporary people are dissatisfied with both their immediate circumstances and with “life itself”—a metaphysical frustration. This frustration diminishes the motivation to resolve life’s problems internally, pushing individuals to increasingly retreat into fantasies.

Animals endure suffering without dissatisfaction with life; ancient people, too, faced hardship without negating life itself. In contrast, contemporary people often reject life even in the absence of suffering. This paradox—denying life while living it—is a defining feature of contemporary times, leading many to replace life with fantasies. In today’s world, where everyone can create their own fantasies, life has increasingly taken the form of a performance. Yet this shift has resolved none of life’s fundamental challenges.

It is often said that contemporary people are confused about life’s purpose—a theme frequently explored in modern literature. Yet the deeper and more troubling reality is that life has genuinely lost its meaning, which is why contemporary people fail to find it. Science fiction, animation, and gaming illustrate this point: the real world, stripped of meaning and attraction, no longer seems worth depicting. As a result, people retreat into fantasies, inhabiting artificial worlds to experience simulated lives and seeking substitutes for the real. Modern fantasies function akin to placebos: they offer psychological comfort but fail to provide a framework for understanding or constructing life’s meaning. By avoiding an examination of suffering, people sidestep life’s most profound questions.

In a post-human world, technological advancements will produce not only more sophisticated fantasy products but also unprecedented material abundance. Human needs may be entirely satisfied, but this apparent utopia hides a deep danger: as material supply is maximized, spiritual vitality tends to be minimized. I cannot shake a hunch that I hope is wrong—that neither traditional religion nor modern ideology will suffice to explain the meaning of life in the future. The post-human world may give rise to a new religion, adapted to the times, that could usher in a new era of obscurantism. In the name of rationality, I hope this does not come to pass.

Zhao Tingyang is a research fellow from the Institute of Philosophy at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Edited by REN GUANHONG