How did the ancient Chinese build a temple on a cliff?

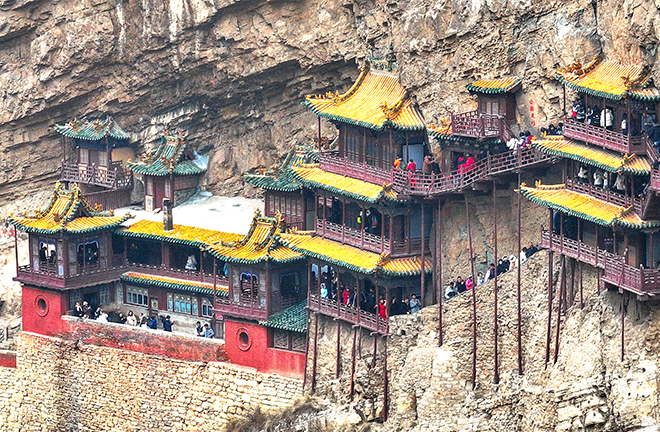

The Hanging Temple complex is the earliest and best-preserved high-altitude wooden cliffside building in China. Photo: TUCHONG

Research indicates that the Hanging Temple was built around 491 in the late Northern Wei Dynasty. Built into the side of a sheer cliff at the foot of Mount Heng, this ancient temple has “hung” on the precipice for over 1,500 years. Its name derives from its seemingly suspended position on the cliff face. Renowned for its precarious location, the temple complex is the earliest and best-preserved high-altitude wooden cliffside building in China. It remains a unique temple combining elements of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, housing statues of Buddha, Laozi, and Confucius together under one roof.

Over the centuries, the temple has undergone numerous repairs, with the current structure dating back to the Ming and Qing dynasties, presenting typical architectural styles of that period. The temple features a “one courtyard, two towers” layout, stretching about 32 meters in length, with the South and North Towers connected by a 10-meter-long bridge. Perched over 50 meters above the ground, it clings to the side of a vertical cliff. When viewed from a distance, its construction seems to defy gravity, appearing to rest on just a few thick wooden pillars.

From ancient texts, we learn that when the Hanging Temple was first constructed, its highest point was over 100 meters above the ground, much higher than it is today. Over time, erosion from rain and the accumulation of sediment have reduced its original height. In an era without blasting techniques or large construction machinery, how was it possible to build the Hanging Temple on a cliff face, with wooden pillars supporting the structures that are no thicker than a bowl’s rim?

The answer can be found in the mountain and the temple itself. A close inspection of the mountain reveals that the Hanging Temple is not located on a sheer vertical cliff but rather situated within a natural groove. The temple’s construction involved artisans using ropes to lower themselves from above, enlarging the natural groove to create a platform where construction could take place. On this platform, the craftsmen embedded hemlock beams into rock. These beams had been soaked in tung oil for an extended period to serve as crossbeams. One end of each hemlock beam was fitted with a wooden wedge, and as the wedge was driven into the stone mortise, it expanded, forming an “expanding dovetail joint,” a traditional woodworking technique primarily used for securing and stabilizing structures through a mortise and tenon connection. Specifically, the shape of the tenon in a dovetail joint resembles a dove’s tail—wide at the top and narrow at the bottom. When a wooden wedge is driven into the joint, the wedge expands under pressure, causing the tenon to fit more securely into the mortise, strengthening both the connection and load-bearing capacity of the joint. A key feature of this structure is that even under external tension, the tenon won’t easily come loose from the mortise, ensuring stability.

The Chinese fir is naturally resistant to decay and moisture. After being treated with tung oil, each beam could bear several tons of weight. This is the secret behind the Hanging Temple’s stability.

The craftsmen transported building materials to the mountain top and lowered them down to the working platform using ropes. Through the assembly of mortise and tenon joints and beam structures, they pieced the temple together step by step, gradually constructing its main body before connecting all the walkways.

The thick beams beneath the pavilions and walkways of the Hanging Temple are deeply embedded into the rock. These beams are key to supporting the entire structure, with a total of 27 in place. Later generations added long logs beneath the Hanging Temple, enhancing the illusion that the entire building is suspended from the cliff.

Craftsmen ingeniously utilized the natural terrain, directing the weight of the entire temple into the rock. Additionally, the overhanging rock above the temple forms a natural roof, providing shelter and mitigating the effect of weathering on the wooden structure by wind and rain. This clever use of natural features is one reason why the Hanging Temple has endured for over a thousand years.

Edited by REN GUANHONG