‘Silk Road’ conceptualized amid Orientalism and colonialism

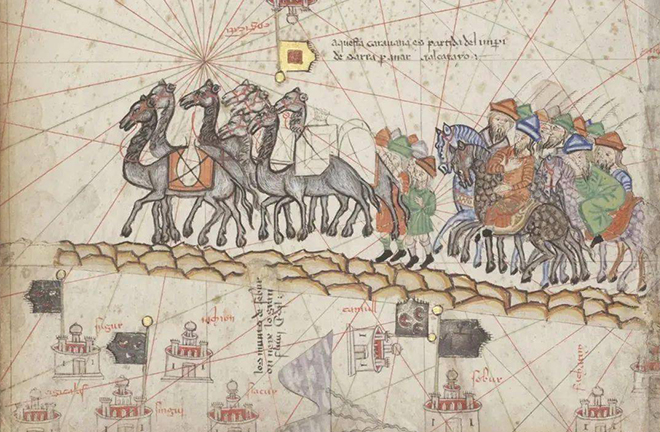

FILE PHOTO: An illustration in the Catalan Atlas (1375) depicting a caravan of merchants travelling along the “Silk Road” before the term was invented

In the late 18th century, Oriental studies emerged as a new discipline in Western academia which was dominated by France and Britain. Some countries and regions along the Silk Road route were former colonies of the West. Their ancient cultures were heavily explored, researched, and even named by Western scholars, as in the cases of Egyptology, Indology, and Assyriology.

The term “Silk Road” was coined by German geographer and geologist Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877 and was quickly recognized by academics in both the East and the West. As a research object, the China-related Silk Road was, however, first conceptualized by a Western scholar in the context of the West’s vigorous expeditions to Central Asia in modern times, and it was mainly studied by scholars from France, Britain, Germany, and Japan. The first book titled The Silk Road was authored by Swedish explorer Sven Hedin, a student of Richthofen’s, and it was published in 1936.

Richthofen and the Silk Road

Richthofen was born in Karlsruhe in Silesia, Prussia, in 1833. After finishing high school, he enrolled at the University of Breslau, followed by the Humboldt University of Berlin. After graduating in 1856, he devoted some time to geological surveying and gained the qualifications to work as a geological expert. Following this, he joined the Eulenburg Expedition as a secretary for the Prussian legation and undertook exploratory missions around the world.

From 1860 to 1862, Richthofen travelled in Asia as part of the delegation sent by the Prussian government to East Asia. The delegation went to many countries, such as Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Japan, Indonesia, the Philippines, Siam (Thailand), and Burma. Although Richthofen didn’t set foot in China this time, he took a keen interest in the geography of China through detailed investigations of its Asian neighbors. Particularly when reading British Orientalist and geographer Henry Yule’s Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, which shed light on transportation routes linking China and the West, his desire to explore Chinese geography grew ever stronger.

In 1868, Richthofen finally visited China with financial support from the US Bank of California. After arriving in Shanghai, he was entrusted by the Shanghai General Chamber of Commerce to survey China’s landforms and geography comprehensively, and thus left his footprints on many places in this nation.

Following his trip in northwest China’s Shaanxi Province, Richthofen planned trips to the Hexi Corridor in Gansu, as well as Xinjiang, but incidents such as uprisings instigated by the Hui ethnic group in Shaanxi and Gansu, and Yakub Beg’s invasion of Xinjiang, disrupted his plan. Despite the failure to visit northwest China, Richthofen offered many suggestions on the building of railways, including a railway along the ancient Silk Road, starting from Xi’an Prefecture, to Lanzhou Prefecture, to Suzhou in Gansu, all the way to Hami in Xinjiang, which was believed to have rich coal resources. The suggested route was to branch out to the south and the north, crossing the southern foothills and northern base of Tianshan Mountain to enter Central Asia.

After returning to Germany in 1872, Richthofen dedicated himself to writing a five-volume geological treatise under the title “China: The Results of My Travels and the Studies Based Thereon.” The first, second, and fourth volumes were published before he passed away in October 1905. The third and fifth books were collated and edited by his students following his passing. All five volumes became available in 1912. In the first volume, published in Berlin in 1877, he first introduced the term “Seidenstraße” (Silk Road).

“Silk Road” appeared four times in the first volume. One of the references was made about a map of Central Asia he drew in 1876, whose caption included “Seidenstraße des Marinus” or Silk Road of Marinus [Marinus of Tyer was a Greek geographer who kept a record of a route to China]. On the map, he drew a basically straight “Silk Road” with a bold red line, which was said to be attributed to Greek geographer Claudius Ptolemy’s atlas Geography. However, the line was directionally inconsistent with the actual Silk Road.

Although Richthofen invented the concept of the “Silk Road,” he made little mention of it in the first volume of the treatise and didn’t discuss or study it in depth.

Academic background

Among products exported by ancient China to the world, silk was most favored by Westerners, so ancient Greeks and Romans called China “Seres,” an ancient Greek word which literally means “the land of silk.”

As early as the 1st century, there had been accounts of Seres in the West. The most credible account was kept by Marinus, and it discussed a path towards Seres, a trade route stretching eastward from the Euphrates ferry to Seres.

In the 2nd century, when Ptolemy was writing Geography, he referred and made corrections to Marinus’s account and documented a route from the basin of the Euphrates River to “Serica,” another term for China, which involved Dunhuang in the northwestern part of the country, and Luoyang in the central region. The trade routes recorded by Marinus and Ptolemy were both related to silk, which became the basis for the term “Silk Road.”

In the late 16th century, thriving European capitalism fueled colonial expansion in the East, with China as one of their targets. Meanwhile, the Jesuits, after encountering setbacks in their fight against Protestantism, also shifted the focus of their missionary campaigns to the East. With the Jesuits’ intensive missionary activities, Europe’s understanding of China was continuously extended and deepened.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Christian priests, diplomats, merchants, explorers, travelers, and scholars from the West came to Eastern countries, including China, in an endless stream. Amid European colonists’ military and economic aggression toward Eastern countries, they also engaged in cultural studies of these nations, thus bringing into being a new discipline—Oriental studies—in Europe.

Among European Orientalists, Yule gathered all ancient Western records, translations, and annotations concerning China in his publication Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China. Especially when excerpting Ptolemy’s Geography, he disclosed all information about Seres documented by Marinus. Yule didn’t use a phrase like the Silk Road in his book, but he was the first to do textual research examining and verifying Seres, and the way to Seres, in other words, China, and the way to China, laying the foundation for the conceptualization of the Silk Road.

Yule’s Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China as well as The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Illustrated Edition kindled a spark of enthusiasm among European Orientalists, including Richthofen, for exploring Eastern society, Central Asia in particular.

Political background

The term Silk Road was also a product of Western colonialism, or the West’s military occupation, economic plunder, and cultural erosion of the East.

After 1840, China was gradually reduced to a semi-colonial, semi-feudal society. In sync with their military and economic aggression, imperialist countries sent large delegations and expeditions to China. As the opening of China’s doors invited an infiltration of Western powers’ military and economic forces, great numbers of missionaries, scholars, and explorers went deep into the country under various pretenses to collect information and serve the colonialists.

Richthofen paid a total of seven visits to China. Starting in late 1869, he secured funds from the Shanghai General Chamber of Commerce for traveling in China for four years, on the condition that he should produce an English report on the Chinese economy, especially on coal mine resources.

Thus, since his fifth expedition, Richthofen had begun to write about what he saw and heard during travel intervals in China via English letters to the Shanghai General Chamber of Commerce.

The letters were later compiled into a book titled Baron Richthofen’s Letters, 1870-1872. Much economic information in the book was very attractive to Western powers at the time. From his reports, it was evident that his expeditions across China had a strong purpose—providing information for aggressors to facilitate their economic expansion.

Although Richthofen’s travels were legal, as a Prussian he believed the loftiest ideal was to help the German Empire become more united and powerful. As early as 1868, when he traveled to Chusan (Zhoushan) in east China’s Chekiang (Zhejiang) Province, he had already realized the significance of the location for transport. It prompted him to write two successive reports, in which he proposed occupying Chusan, and requested that the German consul-general pass this recommendation on to then Minister President of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck. His proposal interested the Prussian government a great deal, but as Britain had incorporated Chusan into its sphere of influence, and the Franco-Prussian War broke out, the scheme fell through.

Following the failure of the Chusan scheme, Richthofen cast his sights on Kiaochow (Jiaozhou) Bay in the Shantung (Shandong) Peninsula. In 1869, he suggested Germany seize Kiaochow Bay alongside the right to construct railways nearby, which would put cotton, iron, and coal at Germany’s more convenient disposal. In 1897, Germany dispatched troops to capture Kiaochow Bay in retaliation for the death of two German missionaries, thereby bringing Shandong under their sphere of influence. In the military plan submitted to Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany, German Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz quoted Richthofen’s expeditionary conclusions many times.

Although the Silk Road was brought up against the backdrop of Orientalism and the West’s occupation and invasion of the East, the concept, or studies of the Silk Road, still possesses a unique scientific value. Despite murky origins, it has since been universally accepted within academia.

Liu Jinbao is a professor of history at Zhejiang University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG