State governance in Yuan era has implications today

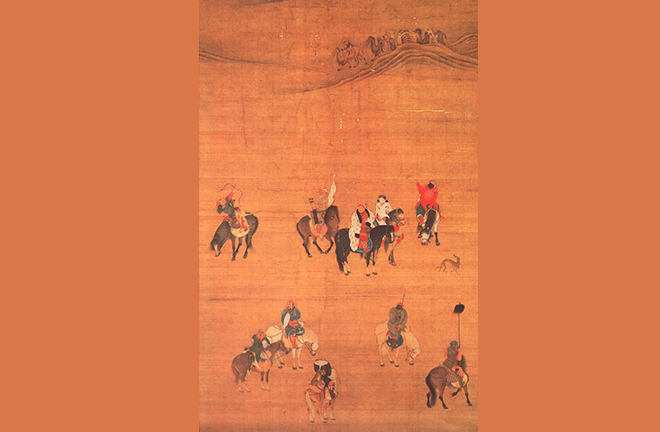

FILE PHOTO: “Painting of Emperor Kublai Khan Hunting” by Yuan Dynasty Artist Liu Guandao

The Yuan Empire (1271–1368) achieved unprecedented great unity (da yitong) in China’s long history, creating a multi-ethnic nation that was ruled by nomads from northern China for the first time. Contributing a unique chapter to the development of China’s big family, it has provided historical experiences and has implications for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation today.

Uniqueness of the Yuan Dynasty

In 221 BCE, Qin Shi Huang, also known as the First Qin Emperor, unified China by conquering the other six states, namely, Han, Zhao, Wei, Chu, Yan, and Qi. Through the Prefecture-County System (Junxian Zhi) which was used to administer the vast territory, the Qin Empire initiated a highly centralized, large-scale state governance model. The following Han (202 BCE–220 CE), Sui (581–618), and Tang (618–907) dynasties largely carried on the Qin’s political systems amid a high centralization of authority and national unification. In the Five Dynasties (907–960) following the Tang, as well as the Liao (970–1125), Song (960–1279), and Jin (1115–1234) ages, China was split by multiple regimes. Mongolian nomads put an end to the national division and reunified the southern and northern parts of China into a state characterized by multi-ethnic integration and unity in diversity.

The Yuan Empire not only established a unified, multi-ethnic nation as never before, but its institutions and culture also generated huge impacts for later generations, particularly the historical course of the subsequent Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, and modern China as well. The most immediate impact is that it laid the foundation for the great unity and political landscape of the Ming and Qing era, which inherited the Yuan’s institutions and cultural heritage including guards and garrisons, postal transportation, food and clothing, the land and maritime Silk Road, and foreign exchanges.

Not only did the Yuan effectively manage diverse ethnic groups, and safeguard the vast unified territory, but it also enriched the traditional Chinese political system and diverse cultures. For example, the System of Administrative Provinces (Xingsheng Zhi), which was instated for local administration, had profound influences on generations to come.

After the reunification of China, the Yuan instituted 10 administrative provinces across the nation, with the aim of guaranteeing centralized authority while maintaining stable regional governance. The administrative system overcame defects in the prefecture-county system implemented during the Qin and Han dynasties, straightened out the relationship between the central government and local authorities, and enhanced the governance capacity of both the imperial court and local governments, playing a vital role in the nearly 100-year multi-ethnic state governance of the Yuan. After the demise of the empire, the system was further developed in the Ming and Qing dynasties, enriching traditional Chinese systems of territorial administration to some degree.

The Yuan Dynasty is unique in Chinese history, in that it combined Mongolian traditions with the systems and cultures of previous dynasties dominated by the Han ethnic group. In the Yuan era, multiple ethnic groups lived together, communicating closely and deeply in politics, economics, and culture. In terms of culture, the Yuan court adopted fairly open policies, carrying forward and enhancing the prosperity of many traditional Chinese cultures, which even outperformed the preceding Tang and Song dynasties in some respects. For example, zaju, literally mixed dramas or theatre, thrived during the period, when such famed dramatists as Guan Hanqing and Wang Shifu gained popularity.

The Yuan also valued social governance a great deal. Especially during the reign of Kublai Khan, each ethnic group was allowed to observe their own customs. Social life was quite open and liberal with regard to languages, religion, culture, marriage, dietary practices, and medical care. In particular, it integrated Eastern and Western science, technology, and medical expertise, set up the People-Benefit (Huimin) Pharmacy to address medical inquiries from civilians, and provided relief for victims of epidemics.

The great unity of the Yuan Dynasty—and its implications for later generations—alongside the multi-ethnic state governance model, are illuminating to contemporary China in state governance, administration of the borderlands, national defense construction, healthcare, ethnic issues, and so forth. Thus, it’s very important to study governance practices of the Yuan Empire as a unified, multi-ethnic state comprehensively and systematically.

Borderland governance

As the first unified, multi-ethnic, centralized regime established by nomads in Chinese history, the Yuan Empire scored unparalleled political achievements in state governance as compared to the past because it basically brought border regions, such as Tibet, the Western Regions, Yunnan, and Lingbei, under direct jurisdiction.

After Prince Godan of Mongolia drew up his strategy for administering Tibet, he invited Tibetan religious leader Sakya Pandita to engage in what was called the “Liangzhou Talk,” in a bid to persuade him to accept Mongolian rule. Following the talk, Kublai and Tibetan scholar-monk Phags-pa built friendly ties and incorporated Tibet into Chinese territory, making it an administrative region under the central government of the Yuan Dynasty.

After Kublai reunified China, the Imperial Preceptorship (Dishi Zhi) was carried out. Recognized as an imperial preceptor in social activities, Phags-pa worked closely with the central government to stabilize Tibet.

Friendships between Godan and Sakya Pandita, and between Kublai and Phags-pa maintained the stability of political situations in the borderlands, and relationships between the imperial court and Tibet.

In terms of Yunnan, Kublai designated Mongol nobles to co-govern the border region with the Duan regime. Meanwhile, he quelled a rebellion staged by his cousin Khaidu in the northwest of China, and a revolt instigated by Nayan in the northeast, stabilizing the Western Regions and the northeastern borderlands, thus making tremendous contributions to borderland governance of the unified Yuan-China.

Administration of the borderlands was different in the Yuan Dynasty from the Jimi System executed by previous dynasties. While the Jimi System allowed each ethnic group to rule themselves, the Yuan court got border areas under direct control. As such, the Yuan ensured a stable political system with ethnic groups in border areas, enhancing mutual understanding between ethnic groups in politics, economics, and culture, and blending them into the community of the Chinese nation.

The Yuan Empire boasted a huge territory with numerous ethnic minorities and different languages coexisting. Official languages included Chinese, Mongolian, and Persian. Extant multilingual documents from the Yuan Dynasty are of great archival value as we examine the Yuan as a unified, multi-ethnic state; the development of border areas; and contact, communication, and integration between various ethnic groups.

Moreover, frontier theories, the administrative province system, the political culture of great unity, and ethnic and borderland issues, have important implications for the formation of China’s frontiers, state governance, administration of the borderlands, international relations, diplomatic thought, ethnic solidarity, the integrated development of culinary cultures from different ethnic groups, customs of ethnic minorities in the borderlands, and the fusion of Eastern and Western science, technology, and medical knowledge.

Yuan contributions

Properly understanding contributions made by the Yuan Empire in Chinese history is worth pondering and needs deeper research. The Yuan Dynasty brought many fresh concepts to China at the time. The impact of its institutional innovation and integration of diverse cultures on later ages deserves further study. We should fully acknowledge the Yuan’s position in Chinese history when inheriting its historical legacies.

First, the Yuan Empire’s land and sea areas were both larger than earlier dynasties, ranking first in Chinese history in terms of territory. Second, the great unity of the Yuan Dynasty played a critical role in bridging divisions between southern and northern China. Multiple ethnic groups co-prospered with diverse cultures. The reunification of all of China by Kublai, particularly, marked the heyday of the Yuan. Furthermore, the great unity of the dynasty had many positive effects on the formation of China as a unified, multi-ethnic nation; promoting contact, communication, and integration among multiple ethnic groups within the territory, and achieving new economic and cultural developments.

The Yuan Empire’s unity along with the contact, communication, and integration of multiple ethnic groups has many positive implications for contemporary state governance, administration of the borderlands, and ethnic solidarity.

First, in the face of the unprecedented vast, unified, and multi-ethnic nation, Yuan rulers made institutional innovations in such fields as state and borderland governance, ethnic issues, and foreign exchanges. The Yuan Empire realized great unity of land and waters to an unprecedented degree in Chinese history, opening up a new stage in the unification of the land territory and diverse ethnic groups. In addition, it laid a historical and realistic groundwork for China’s sea borders, enriched historical experiences on maritime governance in Chinese history, strengthened the cohesion of and sense of identity with the maritime culture of the community of the Chinese nation.

Second, the Yuan regime, dominated by nomads in northern China, created a new model for the contact, communication, and integration of multiple ethnic groups within the Chinese nation, offering illuminations to contemporary China in this regard.

Third, the Yuan court generated unprecedented clout in the world on behalf of the Chinese civilization, spreading Eastern culture and expanding Chinese civilization’s sphere of influence substantially.

Fourth, correctly understanding the positive value of the history and great unity of the Yuan Dynasty can provide a theoretical basis from which to refute such groundless claims as “the Yuan Dynasty or the Mongols don’t belong to China.” History scholars in the new era shoulder the responsibility of popularizing the history and major historical events of the Yuan Dynasty, so correctly evaluating the unique historical contributions of the Yuan in Chinese history is particularly important to positive understandings of Yuan history in the public.

Fifth, the Yuan’s successful experiences and lessons in governing the borderlands, building a powerful coastline, and administering the unified, multi-ethnic nation, are of much theoretical and historical significance to implementing the Belt and Road initiative and accelerating the building of a strong maritime country in the contemporary age.

Oyun Ghuwa is a research fellow from the Institute of History at the Chinese Academy of History under CASS.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG