Holistic EI theory echoes traditional Chinese wisdom

Traditional Chinese wisdom emphasizes the phenomenological analysis and classification of individuals and their behaviors in reality. Photo: Chen Mirong/CSST

Since the proposal of the concept of “emotional intelligence” (EI), also known as “emotional quotient” (EQ), it has been considered a gauge of emotional and affective literacy. Some people even contend that EI is a critical factor determining the success of one’s career and the measure of overall qualities. The concept is also abused nowadays, as sophisticated and duplicitous sycophants are considered emotionally intelligent, while those straightforward, earnest, upright, and impartial are regarded as having a low EQ.

The abuse and misunderstanding of EI can be very misleading, so it is necessary to clarify the concept. With a long history of more than 5000 years, China has its own views on EI. Reviewing these views and comparing them with Western theories is conducive to improving life quality by applying the wisdom of emotional management.

EI theories

The term “emotional intelligence” was first introduced by German psychiatrist Hanscarl Leuner in 1966. In 1995, American psychologist Daniel Goleman compared the concept to “intelligent quotient (IQ)” in his book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ and defined emotional intelligence as an individual’s ability to understand their own emotions, rein in impulses and anger, deal with affairs rationally, and stay calm and optimistic in the face of tests.

In 1997, American psychologists John Mayer and Peter Salovey modified the meaning of EI to emphasize the cognitive element of emotions. In 1998, Goleman proposed an Emotional Intelligence Competence Model in the book Working with Emotional Intelligence.

Based on their own research, Chinese academics built a basic structure for EI, which includes the capacities to recognize one’s own emotions, perceive others’ emotions, think about emotions, and monitor emotions. Other scholars identified EI as humans’ non-cognitive mental abilities that affect their success in study, life, and work, including self-awareness, evaluation, adaption, regulation, and expression of emotions. Each can be further divided into several secondary factors.

As the human brain and its functions are an integral whole, emotion and cognition are complex processes involving the intricate interplay among multiple physiological and psychological levels. The relationship between emotion and cognition should be examined using a holistic approach.

“The question of which (of emotion and cognition) is temporally first, is an epistemological error,” said American psychologist Richard Lazarus, adding that the independent identities of cognition and emotion are more or less fictions of scientific analysis, whose independence doesn’t truly exist in nature. Both analytic reduction and holism are credible, but the best view is that emotion and cognition are always “conjoined” and “interdependent,” Lazarus said.

If the relationship between emotion and cognition is interpreted as physically linked to the relationship between emotion and intelligence, it is justifiable to say that emotion and intelligence are also conjoined and interdependent. Intelligence is a determinant of emotion and a necessary precondition for it. Meanwhile, emotion is independent, regulating and guiding intelligence to some extent. In a sound human body, emotion and intelligence check each other. Whereas emotion controls the focus and direction to, and in which, intelligence functions; intelligence adjusts the intensity of emotion and the direction in which emotion is evoked and unleashed.

Simple dichotomy does not fully outline the relationship between emotion and intelligence. The two should be studied together, holistically.

Chinese classification of personality

In fact, traditional Chinese wisdom also offers a holistic stance on how we should act, such as the notions of “square” (fang) and “round” (yuan). “Square,” a word originally used to describe shapes, like rectangle and quadrate, can be extended to mean propriety and framework for conducting oneself. “Round” refers to circles or circular things, implying diplomacy, sophistication, or worldliness. It can be counted as an approach to, or tactic for, life.

If a man has square inner characteristics or personality traits, it suggests that he has clear moral standards, principles, and a bottom line to stick to. In any situation, he would “follow what his heart desired, without transgressing what was right,” as it’s said in the Confucian classic The Analects. He may even defend his principles at the cost of his life, “never corrupted by wealth, changed by poverty, and bent by force,” to quote Mengzi.

Round, on the other hand, is more about attitudes and strategies applied to the outside world or to handle various relationships, stressing flexibility to achieve best results.

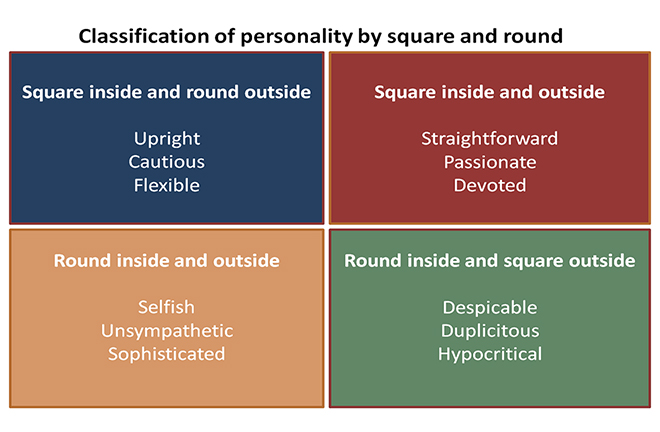

On this basis, ancient Chinese classified humans into four personality types: square inside and round outside; square inside and outside; round inside and square outside; and round inside and outside. This classification doesn’t pale in comparison with famous modern Western psychological theories, such as the Big Five Personality Traits, the Big Seven Model of Personality, and the Enneagram of Personality.

Those categorized as square inside and round outside are capable of keeping their moral integrity, experienced in socializing, and cautious and meticulous. They adhere to principles yet are flexible. Because they are smart and competent, while keeping a low-profile, along with a poker face, they usually can handle complicated interpersonal and interest relationships with ease. As a famous Chinese saying goes, the “lesser hermit” lives in seclusion in the countryside, the “intermediate hermit” does so in the city, and the “greater hermit” achieves it in the central court.

Some capable men hope to leverage their surroundings to retreat away from worldly affairs, indulging in an idyllic life while keeping the fundamental philosophy of life in mind; they are lesser hermits. Those truly capable can conceal themselves in bustling streets, living effortlessly in places full of undiscovered talent, but they are only intermediate hermits. Real hermits are top-notch talent who hide themselves in the central court, responding to political intrigue coolly and wisely and achieving success in one way or another in the whirlpool of political affairs. Zhuge Liang (181–234), a clear-sighted military strategist of the Three Kingdom Period, and modest, self-disciplined late-Qing statesman Zeng Guofan (1811–1872) are typical examples of people with an internally square and externally round personality.

The square inside and outside type is generally characterized by frankness, passion, a serious life attitude, devotion, and integrity. Their vibrancy unavoidably leads to ostentation. Nonetheless, their deeds accord with their words. Qu Yuan (340–278 BCE), a loyal politician of the Warring States Period, and righteous, selfless Song Dynasty official Bao Zheng (999–1062) are representatives of this type.

Some people say it is unimaginable to live without people of this kind, because they clear the “dirty air” and prevent shameful acts in society. Without their uprightness and conscientiousness, bad practices would be unrestrained and would even gain ground. They are defenders and victims of justice many times.

Internally round and externally square people feature a rotten interior beneath a fine exterior. They are sometimes described as decent and solemn in appearance, yet excessively selfish within. They can be impassioned gentlemen in public, but do horrible, despicable things in private. They say one thing but do another, thus are highly hypocritical. If they obtain a post within the government, their subordinates and colleagues will suffer. In front of interests, they are shameless.

People with a round personality, inside and outside, either fail to build a set of socialized standards for the way they should behave or believe that the norms of being “square” are unfavorable. Therefore, they have no internal restraints or discipline, and seldom search for the real meaning of life. Sly in society, they will scramble for whatever brings benefits and honor and avoid the opposite.

Different from the interiorly square and exteriorly round type, most of these people never sympathize with the vulnerable or relieve the poor. Instead, they will scheme against and defame others for their own self-interest. Due to a lack of indomitable spirit, they hardly have a bright future.

Implications of Chinese wisdom

The above four types of personality are common in life. This is an inevitable product of human and social development. However, not all people perfectly fit into one of the categories. Just like the classification of introverts and extroverts, extremely introverted or extroverted people are few and far between. Some lean towards the introverted end, some towards the extroverted, and some are in the middle. The five types are also not all-encompassing. The best practice is to place specific individuals at a certain position between the two ends; this will reveal more salient personality traits.

Distinct from EI theories, traditional Chinese wisdom takes “square and round” as the measure of personality types, emphasizing the phenomenological analysis and classification of individuals and their behaviors in reality. It doesn’t necessarily have a strong structural dimension, but we can still learn to study personalities and how to conduct ourselves through this analytical approach.

The five factors of EI in theoretical terms—self-awareness, evaluation, adaptation, regulation, and expression of emotions—refer only to individuals’ abilities to treat and manage emotions comprehensively. These abilities may be free from interest considerations.

However, humans are complicated. Human nature is inclined, and likely, to pursue maximum interests. Hence the five factors, particularly emotional regulation and expression, usually involve interests in real life, which EI theorists may have never considered.

EI theories basically depict the characteristics of people with different levels of emotional intelligence. They attach more importance to the management of individual emotions, and the identification of, and communication over, others’ emotions. They are more interested in interpersonal relations.

In contrast, emotional intelligence, as defined by square and round in traditional Chinese wisdom, highlights the types of personality and explores the fundamental nature of each type. For example, people round inside and outside, as well as internally round and externally square, may be appraised as highly emotionally intelligent, but they are probably immoral and good at disguising their intentions. Those with a square interior and exterior are so straightforward that they may easily offend others. However, in most cases, these square personalities are “good medicine,” which, though bitter, will cure sickness. Only by enhancing our ability to distinguish right from wrong can we not disdain, complain about, and even hate these personalities as people with a low EQ. By combining EI theories and traditional Chinese wisdom, we can enrich individual-based psychological theories and provide more effective guidance for how we should act in society.

Song Guangwen is a professor of psychology from Guangdong University of Foreign Studies.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG