Beijing Winter Olympics boosts sports diplomacy studies

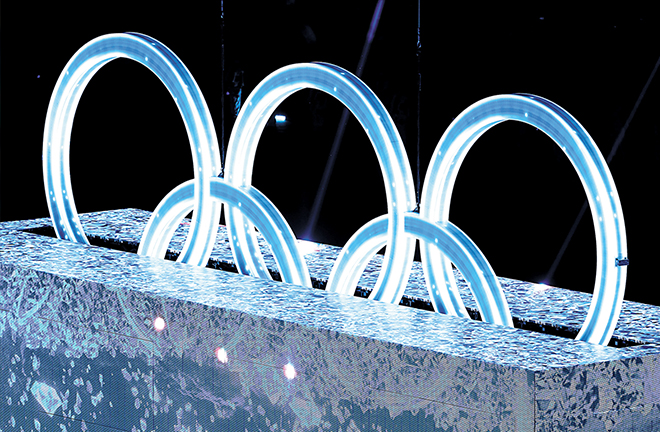

The 2022 Winter Olympics officially opens the night of Feb. 4 in Beijing. Photo: CFP

The 2022 Winter Olympics officially opened the night of Feb. 4 in Beijing. Having already successfully hosted the Summer Olympics in 2008, Beijing became the first city ever to have staged both summer and winter versions of the Olympic Games.

Following the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, a classic case study of sports diplomacy, the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics will also provide significant practical and theoretical contributions to research in this field.

Sports diplomacy growing

Stuart Murray, an associate professor of International Relations at Bond University in Australia who has long been committed to sports diplomacy, said that sports diplomacy can be simply understood as a new term to describe a very old practice—the use of sport to bring people, strangers, and the institutions they form closer together via a shared love of physical pursuits.

Once described as “unloved, under-resourced, and under-represented,” sports diplomacy has become an essential component of diplomacy and international relations. Tim Harcourt, a professor and chief economist from the Institute for Public Policy and Governance at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia, noted that once events like the Olympics and World Cup were televised to a mass global audience, politicians and global business leaders understood “the power of sport in national pride and communications.”

Murray said that the reason behind the growth of sports diplomacy practice is simple: “sport, like music or art, is a universal language that transcends division.” Nowadays, it’s not only governments who play the sports diplomacy game. State and non-state actors, as well as athletes, use sports diplomacy to build relationships, amplify social, political, and economic messages, and advance strategic policy or business objectives. Sports diplomacy complements traditional diplomatic strategies, raises cultural awareness between states, and strengthens international relations on and off the field of play.

Many countries are tailoring their sports diplomacy strategies to target specific outcomes. For example, Australia is using sport to enhance its international reputation and develop partnerships with other countries and regions, and one endeavor is its “Sports Diplomacy 2030” strategy.

Sports can transcend language barriers and sociocultural differences and help build bonds between nations. There are countless examples of successful sports diplomacy practices. For example, “ping-pong diplomacy” between China and the United States in the 1970s ushered in the normalization of bilateral relations. The delegations of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and South Korea marched together in the opening ceremonies of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, the 2004 Athens Olympic Games, the 2006 Turin Winter Olympics, and the 2007 Changchun Asian Winter Games. This scene was not seen again for many years, due to the tense situation on the Korean Peninsula. At the opening ceremony of the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics in South Korea, however, athletes from the DPRK and South Korea marched together under a unified Korean flag, which became another historic moment.

Compared with conventional diplomacy and international trade, sports diplomacy can provide extra benefits. The Beijing Winter Olympics is “hugely significant” to both the theory and practice of sports diplomacy, Murray observed. The 2008 Beijing Olympic Games is already a very popular case in sports diplomacy studies. During the 2008 Opening Ceremony, billions of people from across the globe “watched on in amazement and saw a vision of a new, powerful, and modern China.”

The context for this year’s Olympics is different from the past. The games have been politicized in some countries, Murray said.

“The true purpose of the Games and the Olympic Movement must, however, be respected—a truce between all warring nations, political neutrality, and a chance for a very tired and stressed local, national, and international population to enjoy some sport.”

Boosting economy and trade

Hosting the Olympic Games and other international sporting events can bring economic benefits. Harcourt said that most of these benefits come in broadcast rights, ticket sales (that are shared with the International Olympic Committee), and tourism and hospitality. There is also employment created by building sports and transport infrastructure. In addition, there are trade benefits, particularly as the host city builds a higher profile for the city and the country.

Harcourt said that the Sydney Olympics generated $1.7 billion in trade and investment for Australia. The Chinese government has also used the Winter Olympics to boost local jobs and domestic tourism. The Games are principally for domestic consumption in terms of tourism, local infrastructure and jobs, he noted.

Commercial sports diplomacy strategies drive deals, open doors to new markets, establish links to international trading partners, and unlock economic opportunity, Murray said. It can also promote a nation as a destination of choice for trade, education, or tourism. “Sports diplomacy creates sustainable partnerships between governments, sports clubs, and national organizations while generating win-win outcomes.”

Improving national soft power

Sport is an important aspect of a country’s soft power. The development of sport can help improve a country’s attractiveness and influence, and provide more opportunities for diplomatic activities.

Sports diplomacy changes perceptions of a country, region, or city, abroad, while amplifying an area’s official culture and values. Physical activities create new relationships, link diaspora communities, and form global networks.

Many athletes already act as “diplomats in tracksuits,” Murray mentioned. They represent their country and its values on the field of play, so it makes sense for them to continue acting as ambassadors away from sporting competitions, building trust between peoples and organizations, and laying the foundations for future diplomatic and business relations.

Chinese infrastructure, aid, and development projects have also helped improve China’s soft power, including what we would call “stadium diplomacy,” Murray said. For example, China aided the construction of the Alassane Ouattara Stadium in Cote d’Ivoire.

“Working together, sport and diplomacy can make the world a much better place,” Murray said.

Edited by JIANG HONG