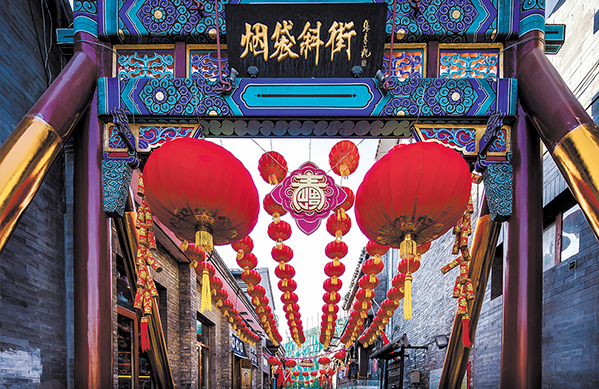

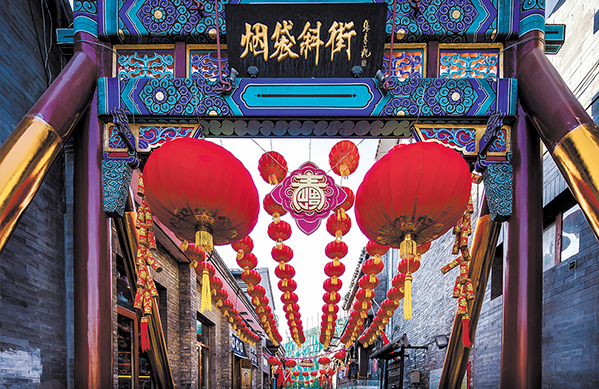

The Yandaixie Street, the oldest business street in Beijing with a history of about 800 years, is decorated around Chinese New Year. Photo: CFP

The Year of the Ox is coming to an end and the Year of the Tiger is about to begin. Having been in Beijing for over 70 years, I have experienced different celebrations of the Chinese Lunar New Year, or the Spring Festival, in many different times. Beijing has been the national capital of the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, and the People’s Republic of China. The Spring Festival celebrated in this city is characterized by the integration of traditional Chinese culture, folk culture, and religious culture, highlighting joy and harmony. Today, many customs, even temple fairs [Chinese gatherings usually held around the time of the Chinese New Year and other traditional festivals], have almost disappeared, but the charm of traditional Chinese culture is permanent.

Laba Festival

Celebrations of the Spring Festival in Beijing actually start from the eighth day of the La Month [the twelfth lunar month]. The eighth day of the twelfth lunar month is abbreviated as “Laba.” On that day, cooking and eating Laba congee is an important event. People in Beijing are very particular about Laba congee—the congee usually contains many ingredients, such as rice, red dates, lotus seeds, walnuts, chestnuts, almonds, etc. Many families start cooking it at midnight on the seventh day of the twelfth lunar month, and then simmer it on a low fire until the next morning. The final step is to add brown sugar to the congee. The Laba congee should first be served to gods and ancestors as offerings, then presented to relatives and friends, and finally shared by the whole family. The leftover congee is also preserved and eaten later, which is considered a good sign, meaning “more than sufficient every year.”

Since the reform and opening up in 1978, people in Beijing no longer serve the Laba congee to gods, nor do they give it to their relatives and friends. They just enjoy the congee themselves. Some even prefer to eat congee provided by temples rather than cooking it at home.

Chinese Buddhists view “Laba” as a Buddhist festival. Therefore, on the day of “Laba,” all Buddhist places of worship around the country have the tradition of holding Buddhist assemblies, making congee offerings to the Buddha, and sharing Laba congee with the public. On the Laba day, lamas [a general title for monks in Tibetan Buddhism] of the Yonghe Temple usually cook Laba congee before dawn, and offer the first bowl of the congee to the Buddha. After the temple is open, lamas carry buckets of Laba congee to the courtyard of the Devaraja Hall, and hand the congee out to everyone who comes to the temple that day.

The Laba congee provided by the Huoshen Temple [a Taoist temple in Beijing, dedicated to worshiping the god of fire] is made of high-quality food materials from different places, including rice from northeastern China, goji berries from the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, red dates from Shaanxi Province, raisins from the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and peanuts from Shandong Province. The other temples in Beijing, such as the Fayuan Temple, Tanzhe Temple, Longquan Temple, and Dajue Temple, also hand out Laba congee to the public on the day of Laba.

Minor New Year

The festive atmosphere of the Spring Festival in Beijing grows much more on the 23rd day of the twelfth lunar month, which is known as Xiaonian, or Minor New Year. Traditionally, the Kitchen God farewell ritual is usually observed on that day. Legend has it that the Kitchen God was sent down to earth by the Jade Emperor [ruler of heaven] to monitor and record all the good or bad manners of each family over the past year. Usually, the niche of the Kitchen God is located in the front of the kitchen, with the statue of the Kitchen God in the middle. The couplets that read “Ascend to heaven and report nice things” and “Return to your palace and bestow good luck” are pasted on both sides of the niche, which are believed to keep the family safe and sound. Another activity is to eat zao candy [which is derived from the custom of smearing the lips of the Kitchen God’s paper effigy with candy to sweeten his words to the Jade Emperor, or to keep his lips stuck together]. The zao candy is made of maltose, sweet and crispy. Small vendors often start to sell zao candy in alleys of Beijing as early as the beginning of the twelfth lunar month.

After the Kitchen God rituals, on the days immediately before the Chinese New Year celebration, families give their homes a thorough cleaning and make chuang hua, a cut-paper art designed for windows. The house cleaning at the end of a lunar year is called “sweeping dust,” or “sweeping house” in Beijing, which starts from the 23rd of the twelfth lunar month and continues to Chinese New Year’s Eve. The cleaned house is then decorated with paper-cut artworks. Designs for cut-paper works vary, from thriving animals and plants to human images. Images such as magpies on a plum tree, two dragons playing with a pearl, and two mandarin ducks playing in water [all these images are auspicious symbols in China] are the most popular.

After the 23rd day of the twelfth lunar month, families paste Spring Festival couplets on both sides of the door. Most couplets are inscribed with auspicious phrases of god worship and prayers for good fortune. Some couplets express festive celebrations and hope.

On the afternoon of New Year’s Eve, almost all families decorate their houses and prepare offerings to ancestors and gods. After the ceremony to worship ancestors and gods on New Year’s Eve, it’s time for “weilu,” which refers to the whole family sitting around a table for New Year’s Eve dinner. After the dinner, elder family members give monetary gifts to younger members [usually children], which is known as yasuiqian [a practice which is believed to ward off evil spirits]. Today, the money is usually wrapped in red paper, commonly known as “red envelopes.”

The first Spring Festival Gala broadcast on CCTV aired in 1983. Since then, watching the Spring Festival Gala together has become a tradition for most families. People staying up all night on New Year’s Eve is called shousui, which is practiced as it is thought to add on to one’s parents’ longevity.

Spring Festival

The first day of the first lunar month is known as Spring Festival. From the first to the fifteenth day of the first lunar month of the new year, the most lively events in Beijing are temple fairs held around Buddhist and Taoist temples. A temple fair is a traditional folk cultural event that integrates folk art, religious beliefs, material exchanges, and cultural entertainment, often attracting thousands of people to participate. The most famous temple fairs in Beijing are held around the Dongyue Temple, Baiyunguan Temple, Dazhong Temple, and the Tanzhe Temple.

The Baiyun Temple is the largest Taoist temple in Beijing. The temple fair around this temple is a traditional folk activity integrating Taoist rituals, singing and dancing, entertainment, and trade. Many folk art performers, such as those doing the lion dance, stilt walking, or land boat dance, come to burn incense and perform, attracting many tourists. There are many games involved in the fair, including “meeting deities” [based on the belief that Master Changchun, a high-ranking Taoist monk, comes to his former residence, the Baiyun Temple, from heaven every year on his birthday, or the 19th day of the first lunar month], “hitting the center of coins” [there is a bridge in the temple, with two coin-shaped bronzeware objects hanging on either side; at the center of each bronze artifact hangs a small bronze bell; it’s said that people who can hit the small bell with coins will have a lucky year], and “touching stone monkey” [there is a stone carving of a monkey in the temple, which is said to be the incarnation of a fairy, and anyone who touches this stone relief will be blessed]. These games are endowed with people’s wishes to ward off misfortune and disasters, and bring good fortune to their families in the new year.

The Tanzhe Temple is located in the west of Beijing. The temple fairs held there include various rituals of praying for good fortune. It is said that the first day of the first lunar month is Maitreya’s birthday. On that day, monks of the Tanzhe Temple hold a grand Buddhist ceremony in the Mahavira Hall, which has been cleaned and well decorated. They celebrate Maitreya’s birthday, and pray for the pilgrims who come to worship the Buddha. The “first stick of incense” on the first day of the first lunar month is regarded as the most auspicious, so many people surge into the Tanzhe Temple to put their first stick of incense of the year into the temple’s giant incense burner, in the hope of ensuring good luck and health for their families for the whole year.

When fragrant smoke of the burnt incense curls upwards and the sound of the temple bell echoes around, the early sun starts to shine on the city of Beijing, signifying a new, beautiful spring.

Zhao Yuntian is a research fellow from the Institute of Modern History at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Edited by REN GUANHONG