Mid-Autumn Festival in ancient paintings

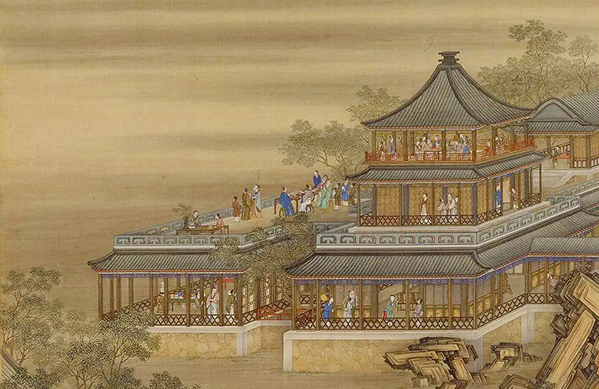

FILE PHOTO: “Appreciating the Moon in the Eighth Lunar Month” by the Italian Jesuit missionary Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766), which is now in the Palace Museum in Beijing

The Chinese people have always put a high premium on the kinship bond since ancient times. The great value put on family reunions is deeply rooted in every person’s mind. In this sense, the Mid-Autumn Festival is the manifestation of traditional Chinese values. There are many romantic legends related to this festival. In addition to historical archives, ancient paintings also provide us with rich information about the Mid-Autumn Festival.

Moon worship and legends

Partly due to primitive moon worship, almost all the traditions and customs of the Mid-Autumn Festival are associated with the moon. The ancients believed that the cyclical process of the sun and the moon laid the foundations for the basic rhythms of life and the universe.

According to the Book of Rites, a Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) Confucian classic, “The sun comes forth from the east, and the moon appears in the west; the darkness and the light are now long, now short; when the one ends, the other begins, in regular succession—thus producing the harmony of all under the sky” (trans. James Legge). The sun and the moon were endowed with the concept of yang and yin, and they were personified as man and woman, respectively.

In ancient myths and legends, the lunar deity was named Chang Xi, and was portrayed as a woman. According to the Classic of Mountains and Seas, an ancient Chinese compilation of mythic geography and beasts, “Inside the Great Wilderness there is a mountain called Mount Sun and Moon, which is the pivot of the sky…… A woman is bathing the moon. She is Chang Xi, wife of King Jun who gave birth to twelve moons. She is the first to bathe them here” (trans. Wang Hong & Zhao Zheng).

The Han Dynasty stone reliefs provide more vivid information—a common image on the stone reliefs includes two deities with human heads and serpents’ bodies. Academics generally think that they are Fuxi [first mythical emperor of China] and Nyuwa [the mother goddess of Chinese mythology, credited with creating humanity], and the two often match the sun and the moon, respectively. It is worth noting that there is a toad in the moon held by Nyuwa. The connection between the moon, women, and a toad, is based on the ancients’ primitive fertility worship. The cyclical process of the moon and the toad’s ability to lay a large number of eggs represented vigorous vitality, and were believed to be similar to the fertile traits of women.

The legend of Chang’e is closely related to Xiwangmu (Queen Mother of the West). Xiwangmu was an important goddess popular from the pre-Qin (prior to 221 BCE) to the Han era. Her image can be found on the Han stone reliefs, too. For example, on a stone relief unearthed from the ancestral hall in Jiaxiang County, Shandong Province, Xiwangmu sits upright, surrounded by winged deities. To her left, there is a toad and a rabbit pounding the elixir of life with a mortar and pestle. Xiwangmu is the owner of the elixir of life.

A more complete version of the story of Chang’e can be found in Ling Xian (Spiritual Constitution of the Universe), an astronomical book by the Han Dynasty polymath scientist Zhang Heng: Hou Yi, a mythological archer, obtained an elixir of life from Xiwangmu to live forever, but his wife Chang’e consumed the elixir herself and flew away. Before leaving for the moon, Chang’e consulted a diviner named Youhuang, who predicted a favorable outcome to her journey. Upon arriving on the moon, Chang’e turned into a toad. The myth of Chang’e flying to the moon was enriched and perfected in the Tang Dynasty (618–907).

The Moon Palace [the palace on the moon], also called Guanghan Palace, is associated with Taoism. It was first seen in the annotations made by a hermit named Bai Lyuzhong for the Huangting Neijing Jing [an ancient treatise on health] during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (r. 712–756). During the Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern Dynasties (220–589), the osmanthus fragrans tree and the deity in the moon began to be linked together. In the Tang Dynasty, the identity of the immortal was settled. According to Youyang Zazu (Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang), a Tang Dynasty miscellany of Chinese and foreign legends and hearsay, there is an osmanthus fragrans tree and a toad on the moon. The tree is over five hundred zhang [a Chinese unit of length equal to 3 or 3.6 meters during the Tang era] high and is self-healing. A man named Wu Gang is forced to chop the tree on the moon endlessly as a divine punishment.

White osmanthus blossoms and the cute moon rabbit, together with bright moonlight, have become synonyms for the Mid-Autumn Festival. The “Osmanthus Blossoms and Moon Rabbit” by the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) artist Li Shizhuo is an excellent example. This painting was created on the day of a Mid-Autumn Festival. What it depicts is a realistic scene, but the painting creates a sense of emptiness beyond the mortal world. Under osmanthus branches, the moonlight is evenly scattered on the ground, and a white rabbit is lying in the grass, with its head up and ears stretched out, as if it is full of yearning for the bright moon high in the sky.

The elixir of life, Taoist Guanghan Palace, and the self-healing osmanthus fragrans tree are all related to the belief in immortality and are full of romanticism. Since then, the Mid-Autumn Festival has gradually become a public festival, celebrated by the court as well as common people.

Festive traditions

The Mid-Autumn Day was not an official festival during the Tang Dynasty, but the custom of enjoying the moon on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month did exist among the literati. Many great poems about the Mid-Autumn Day were created.

It was not until the Song Dynasty (960–1279) that the Mid-Autumn Day officially became a popular festival. The earliest record of the Mid-Autumn Festival in the Song era is found in the Dongjing Menghua Lu (The Eastern Capital: A Dream of Splendor), a memoir written by the Song writer Meng Yuanlao: as the Mid-Autumn Festival was coming, all the restaurants [in the Song capital, located in present-day Kaifeng, Henan Province] began to sell newly brewed liquor and redecorated the cailou [a traditional architectural arch in front of restaurants, generally used to celebrate festive events] with colorful silk. Colorful jiuqi [flags hanging outside taverns and restaurants as advertisement in ancient China] with the image of “Zui Xian” [Drunk Deity] were hung on painted poles outside restaurants. Citizens rushed into restaurants to have a sip of the newly brewed liquor. Around noon, all the liquor had been sold out, and restaurants had to take down their flags. During the Mid-Autumn Festival, the autumn delicacies—crabs, pomegranates, quince fruits, pears, dates, chestnuts, grapes, and tangerines—were sold at the market. On the night of the festival, noble families enjoyed the full moon on their grand terraces, while commoners crowded restaurants to appreciate the moon, with music lingering in the air. Residents close to the imperial palace could hear music from the palace in the middle of the night, just like a fairy melody from beyond the clouds. Children in alleys played all night long. The night markets were lively and were open until dawn.

During the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing dynasties, celebrations of the Mid-Autumn Festival included more sacrificial rituals, and the ethical significance of family reunions was highlighted, which was especially obvious among the common people. The Dijing Jingwulue (Brief Account of the Sights of Imperial Capital), a 17th-century Chinese prose classic, records the Mid-Autumn Festival customs in the capital city of Beijing: among all the offerings to the moon on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month, all the fruits and cakes must be round, and watermelons must be carved into the shape of lotus petals. Yueguang Paper [Moonlight Paper, a paper image of a god usually laid at the center of the altar] was on sale in stores. On the Yueguang Paper there are images of Candraprabha sitting atop a lotus flower, and the moon rabbit standing like a human, grinding the elixir of life with a mortar and pestle. After performing the rituals of worship, the offerings are shared by all the family members.

The imperial palace at that time retained more of the previous customs of the Mid-Autumn Festival. “Appreciating the Moon in the Eighth Lunar Month” is from a set of court paintings collectively titled “Twelve Months,” in which the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723–1735) was portrayed participating in the traditional festivities in each of the twelve lunar months. “Appreciating the Moon in the Eighth Lunar Month” depicts how the Yongzheng Emperor, dressed in a green gown, enjoyed the Mid-Autumn Festival with guests on waterside pavilions. His concubines were enjoying the reflection of the moon in water in the other pavilions or courtyard. The courtyard is full of seasonal flowers such as the osmanthus blossoms. What an autumnal view!

For thousands of years, the moon has been endowed with many blessings, either in romantic words or in exquisite paintings. Those works of literature and art about the Mid-Autumn Festival represent the Chinese people’s cherished bond of kin, which has been handed down through generations.

Mao Xiangyu is from the Department of Paintings and Calligraphy at the Palace Museum.

Edited by REN GUANHONG