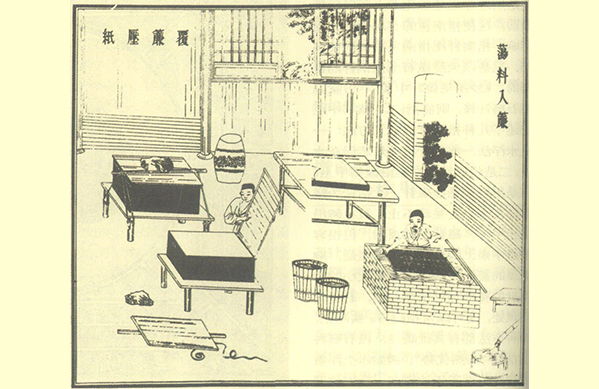

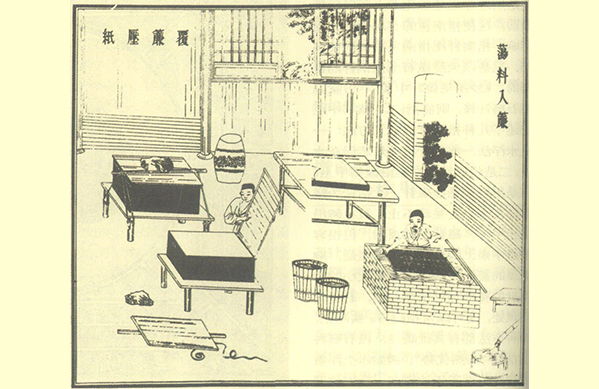

FILE PHOTO: An illustration of the papermaking process in Tiangong Kaiwu, an encyclopedia covering a wide range of technical issues compiled by the Ming Dynasty scientist Song Yingxing (1587–1666)

The compass, gunpowder, papermaking, and printing are collectively known as the “Four Great Inventions” of ancient China. They have made important contributions to the progress and development of human civilization. However, for a long time, there have been disputes in academia regarding the time of the invention of the papermaking process and whether Cai Lun [an Eastern Han (25–220) eunuch traditionally regarded as the inventor of the “Paper of Marquis Cai” and the modern papermaking process, c. 61–121] invented or improved papermaking.

Since the 1930s, many “ancient paper” [precursors of paper, some are called “paper-like material”] fragments have been unearthed, by which scholars verified that paper mainly made of plant fibers had been used in the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–8 CE). However, whether the invention of the papermaking process should be attributed to Cai Lun, and how to understand the historical records of Cai’s achievements, still needs to be clarified. In fact, regardless of whether papermaking originated in the Western Han or the Eastern Han, or whether Cai was the inventor or improver of the papermaking process, the invention of papermaking was closely related to the mainstream academic culture of the time—jingxue (classics scholarship), or the study of Confucian classics. This historical context has long been ignored by academics.

Classics scholarship of the Han Dynasty

The study of Confucian classics thrived during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Under the rule of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE), Confucianism was established as the state cult, thereby boosting the study of Confucian classics in the country. As the mainstream ideology of the Han Dynasty, classics scholarship exerted a deep influence on society politically, culturally, and academically. It gradually penetrated into all aspects of social life. It is worth noting that the study of Confucian classics during the Han era was not only scholarship, but also provided access to the civil service ladder for intellectuals. Having a good knowledge of Confucian classics was an important criterion for the court in selecting talent at that time.

The unique status and influence of the Han Dynasty study of Confucian classics inextricably bound it up with papermaking. Generally speaking, the invention and improvement of the papermaking process were cultivated amidst the background of the Han Dynasty study of Confucian classics.

‘The lighter, the better’

The “Paper of Marquis Cai” invented by Cai Lun was viewed as the earliest form of paper recorded in the historical archives. Cai’s biography in the Book of the Later Han [an ancient book covering the history of the Han Dynasty from 6 to 189 CE] says: “In ancient times, writings and inscriptions were generally made on tablets of bamboo or on pieces of silk called paper. But silk being costly and bamboo heavy they were not convenient to use. Cai Lun then initiated the idea of making paper from the bark of trees, remnants of hemp, rags of cloth, and fishing nets. He submitted the process to the emperor in the first year of Yuanxing (105 CE) and received praise for his ability. From this time, paper has been in use everywhere and is universally called the ‘Paper of Marquis Cai.’” Another book of history titled Dongguan Hanji has a similar statement regarding Cai. The records about Cai’s invention in these two books have been recognized by many scholars.

Why did Cai invent or improve the papermaking process? People often ascribe the invention of the papermaking process to the practical value of paper, compared with the inconvenience of bamboo slips and costliness of silk manuscripts. This ignores the underlying social and cultural factors—bamboo slips as a writing material restricted the circulation and dissemination of Confucian classics. Developing rapidly in the Eastern Han Dynasty, classics scholarship was in urgent need of a writing material that was more portable, easy to obtain, convenient to write upon, and provided more space for characters.

During the Eastern Han era, repeated interpretation and extension of the meaning of classics made Confucian texts much more cumbersome. This problem attracted growing attention from scholars. The Book of the Later Han records that Emperor Guangwu of Han (5 BCE–57 CE) used to be so worried about the overloaded materials of the Five Classics [The Five Classics are five of the Six Classics excluding the Classic of Music, which is generally believed lost] that he issued an imperial decree to condense and simplify those texts. However, the result was not so successful.

As the annotations and explications of Confucian classics became more and more complicated and tedious, “many schools of thought on classics scholarship emerged, each with numerous doctrines. Some annotations and explications of the classics even included more than one million characters. Great efforts into the study of Confucian classics produced little result. Young students were troubled and full of doubt, but they couldn’t find the answers” (see Book of the Later Han). Therefore, since the middle and late Eastern Han Dynasty, scholars had become increasingly eager to simplify the Confucian texts.

As the political, economic, and cultural center of the Eastern Han, Luoyang [in present day Henan Province] enjoyed a prosperous academic culture and advanced educational resources. This city was widely admired by ambitious intellectuals. Taixue (Imperial Academy), the highest institution of learning at that time, was located in Luoyang. In order to increase their knowledge and to obtain career opportunities, many intellectuals left their hometowns for study tours and travelled with books and other learning materials. However, bamboo slips were too heavy and silk was too expensive. The inconvenience of travelling with books severely affected intellectuals’ study tours and restricted the dissemination of classics. In this context, Cai creatively invented the papermaking process.

During the Eastern Han, Prince Hu ascended the throne and became Emperor An of Han (r. 106–125) when he was young, so Empress Dowager Deng served as the regent. Empress Dowager Deng attached great importance to sorting and revising documents and archives. She ordered knowledgeable Confucian scholars and excellent historians to proofread books and revise classics at Dong Guan (imperial library). Cai was the supervisor of this project. The main reason why Empress Dowager Deng chose Cai to take charge of the project was that Cai had a good command of Confucian classics and a full understanding of the cumbersome materials of the classics.

Access to imperial court

Since the reign of Emperor Wu of Han, Confucianism became the official ideology of the nation. Familiarity with Confucian classics was the main condition for entry into government posts in the Han Dynasty. At that time, classics scholarship had a wide influence upon the civil servant selection system, economic policy, legal system, disaster relief measures, ethnic policy, etc. Chaju Zhi [a system through which candidates for offices were recommended by the prefect of a prefecture, examined, and then presented to the emperor] was the primary path to civil service during the Han era. This recommendation system was closely connected with the study of Confucian classics. An examination for classics scholarship, known as mingjing, was introduced to the Chaju system. Candidates were tested on the Confucian canon, and the one who was best at classics would be selected to serve by the emperor’s side. This system directly promoted the prosperity of classics scholarship and drove intellectuals to explore Confucian classics during the Han era.

With his special status in court, Cai was able to get in touch with a large number of Confucian scholars and intellectuals. He knew their difficulties in studying the classics and the big inconvenience of using bamboo slips as writing material. It might explain why he invented the “Paper of Marquis Cai.”

It can therefore be concluded that the invention of papermaking was closely linked with the study of Confucian classics during the Han Dynasty. It was the cultural background and academic characteristics of the Han era that gave birth to the invention of the “Paper of Marquis Cai.”

Zhao Yulong is a lecturer from the School of Chinese Language and Literature at the Inner Mongolia Normal University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG