Theoretical study of women’s literature to be enhanced

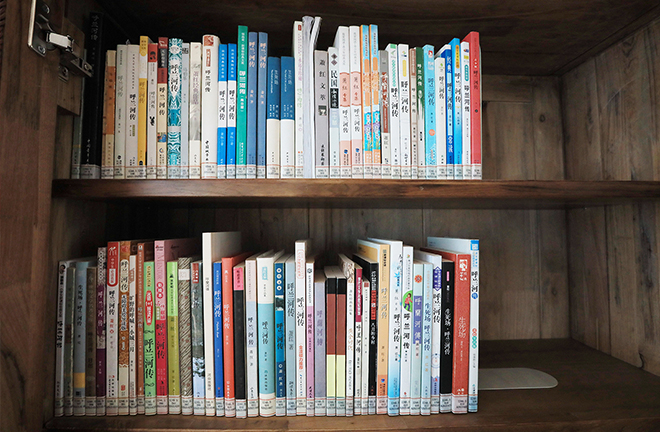

Different editions of Tales of Hulan River, written by female writer Xiao Hong (1911–42), displayed at Heilongjiang Provincial Library in Harbin, Heilongjiang Province Photo: CFP

Women’s writing and gender studies in literature have become a hot research topic in the literary field. Since the beginning of the 21st century, China has further developed women’s literature studies, especially regarding women’s literary creation and feminist literary criticism. Despite this, women’s literature theory needs to be intensified.

Interdisciplinary research

“The study of women’s literature examines the existence, process, and state of female life in historical and present contexts from sociological, cultural, anthropological, and ecological perspectives, indicating clear directions for Chinese women’s writing,” said Tian Meilian, a research fellow from the Institute of Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

“1995–2005 saw a rocketing development period in Chinese women’s literature studies,” said Wang Kan, a professor from the School of Humanities at Hangzhou Normal University. The stage is strongly linked to the increasingly open market space, as well as the highly diverse cultural pattern, and the people’s increasing individual consciousness and gender consciousness since the 1990s. Since the mid-1990s, in the graduation theses from Chinese language and literature departments of colleges and universities, research topics on women’s literature have multiplied, and research teams have constantly expanded, yielding a substantial batch of fruitful research. All these have quickly solidified women’s literature as a brand-new discipline. Over the past decade, Chinese women’s literature studies have entered a relatively stable period. Whether as a discipline or an academic field, women’s literature has shown a trend toward maturity.

“Researchers harbor an increasingly rational understanding of women and women’s literature,” said Dong Limin, a professor from the School of Humanities at Shanghai Normal University. Nowadays, scholars of women’s literature attach importance to the collection and compilation of historical documents and the introduction of interdisciplinary research methods. They also strive to explore effective paths for the classicization of important women writers and their works. At the same time, gender perspectives and literary research have combined ever closer. There has been significantly increasing awareness and ability of interaction between women’s literature research and social historical contexts. In addition, interdisciplinary research that integrates women’s literature with ethnic and media dimensions has gradually become a trend.

According to Wang, the discipline has never been “pure literary study.” In order to advance in-depth studies of women’s literature, researchers are expected to have an interdisciplinary vision, continuously drawing theoretical and spiritual resources from other fields, especially political science, sociology, and cultural studies.

Theoretical construction

“The discipline can be largely categorized into three research fields: the history of women’s literature, feminist literary criticism, and the construction of feminist theory,” said Guo Bingru, a professor from the Department of Chinese at Sun Yat-sen University. These three sections have experienced unbalanced development. Comparatively speaking, the history of women’s literature has seen more in-depth research. It reviews the history of women’s writing from the perspectives of society, economics, culture, and education, establishing a complex relationship between literature and the world from a cross-disciplinary perspective. Feminist literary criticism possesses the most research results, which derive from the prosperity of women’s literary writing. The construction of feminist theory is the weakest, with the discourse system of feminist criticism yet to be established.

“Women’s literature and feminist theory constitute an obvious interactive relationship,” Guo continued. The lagging theoretical construction has given rise to a host of contradictions and differences between women’s literature and feminist criticism. The vast majority of women authors are unwilling to be positioned as “women” writers, reluctant to be labeled as “feminism,” and don’t even want their works to be regarded as “women’s literature.” Furthermore, expressing gender awareness and reflecting gender-related issues are not compulsory themes of women’s writing. As such, scholars are tasked with investigating how to match feminist theory and increasingly diverse women’s writing and how to establish a gender theory suitable for the local context and the development trend of women’s literature.

In Dong’s view, women’s literature researchers have insufficient awareness and capacity for theoretical dialogue with mainstream academia. There also lacks a systematic and integrated compilation of women’s literature. Marked progress has yet to be made in the concept of women’s literature history, historical staging, and standards for classic writers and their works. Therefore, the study of women’s literature must be based on itself, and at the same time, absorb multidisciplinary research results, in order to consolidate theoretical construction and seek new discourse for the discipline. The future of women’s literature research depends to a large extent on whether it can realize the construction of its own discourse system.

“Women’s literature research can find more powerful resources, paths, and methods only via truly handling its complex interaction with history, society, culture, ideology, knowledge and other fields,” Dong added.

“The goal of feminist theory construction aims not only to study women’s literature, but more importantly, to establish a knowledge system for understanding the world and oneself,” Guo concluded.

Edited by YANG LANLAN