‘Liaozhai’ meets French ‘Fantastique’

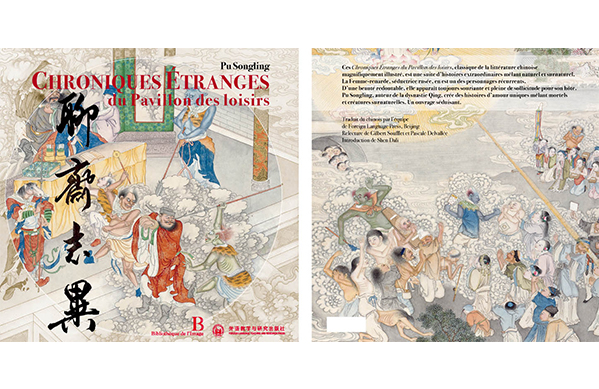

FILE PHOTO: The cover of the French version of Liaozhai Zhiyi

At the end of 2020, China’s Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press and the French publisher Bibliothèque de L’Image co-published the illustrated French version of Liaozhai Zhiyi (hereinafter called Liaozhai) in traditional Chinese bookbinding. The publishers noted that this was the first illustrated French version of Liaozhai published overseas. The FNAC, a French retail chain in charge of the distribution of the book, said that the main characters of this Chinese classic are beautiful, kindhearted “fox fairies,” and this imagery inspired many artists.

‘Liaozhai’ distinct from Western tales

Liaozhai is a “pool of thoughts.” According to observations of Liaozhai made by French sinologist André Lévy (1925–2017), this book amazed readers with its unusual charm. He claimed that Liaozhai was unrivalled in the republic of letters. When comparing Liaozhai with traditional Western fairy tales, a French literary critic noted that Western strange stories are usually set in an epoch when animals can speak, and the characters of these stories live in an imaginary world, which is regulated by secular rules. In China, however, all the fairies, demons, and ghosts live among human beings, and share the same values as humans in the most natural manner.

From Pu’s own preface, readers get an inkling of why the author wrote Liaozhai: “I am but the dim flame of the autumn firefly, with which goblins jockeyed for light; a cloud of swirling dust, jeered at by mountain ogres. Though I lack the talent of Gan Bao (280–336, author of Soushen Ji, or In Search of the Supernatural), I too am fond of ‘seeking the spirits;’ in disposition I resemble Su Shi (1037–1101, a renowned Song Dynasty scholar), who enjoyed people telling ghost stories. What I have heard, I committed to paper, and so this collection came about” (trans. Judith T. Zeitlin).

There is no “prince-worship” in Liaozhai, which is very common in the fairy tales by Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, and Hans Christian Andersen. What the Liaozhai tales try to tell goes beyond earthly aspirations reflected in Western fairy tales, such as “Sleeping Beauty,” “Cinderella,” “Bluebeard,” and “Snow White.”

“The uncanny” vs “the fantastique”

Franco-Bulgarian literary critic Tzvetan Todorov (1939–2017) introduced the concept of Fantastic literature (la littérature fantastique). He sorted the Fantastic into the “étrange” (Todorov translated ‘étrange’ into ‘uncanny’) and the “fantastique.” Liaozhai is a combination of the “uncanny” and the “fantastique.” It features “weirdness and fantasy” as a traditional Chinese Fantastic, which is different from its European counterpart’s tendency to be “pure and beautiful.” Take the Liaozhai tale “The Girl in Green” for example: One night, a beautiful lady in a green dress visited a man named Yu Jing when he was studying in a temple. They fell in love with each other. One day, Yu heard the girl crying for help. He ran around, searching and listening. Soon, he found her voice coming from the eave of his house and saw a spider had caught a little insect. He broke the spider web and rescued the insect, which turned out to be a green bee. The green bee jumped into the ink slab and then came out again, crawling on the desk to finally create the word “thanks.” Then it flew away. The girl in green never returned.

In one of his Victory Odes, the ancient Greek lyric poet Pindar (518–438 BCE) wrote: “A dream of a shadow is our mortal being.” Inspired by this line, the French poet Gérard de Nerval (1808–1855) wrote The Daughters of Fire (Les Filles du feu). In this book, Nerval attempted to fit his dreams into the real world. This boundary-blurring approach represents a common feature in the French Fantastic, except for Charles Perrault’s fairy tales. The influential French author Jean Charles Emmanuel Nodier (1780–1844) highlighted the importance of dreams as part of literary creation.

Pu created a magically real world distinct from the world of French Fantastic.

Escaping from worldly vanity

Pu saw through the vanity of quotidian life. In his own Preface to Liaozhai, Pu wrote: “My excitement quickens: this madness is indeed irrepressible, and so I continually give vent to my vast feelings and don’t even forbid this folly. Won’t I be laughed at by serious men? …… I could still have realized some previous causes on the ‘Rock of Past Lives.’ Unbridled words cannot be rejected entirely because of their speaker!” (trans. Judith T. Zeitlin).

In the story ‘The Raksasas and the Ocean Bazaar,’ [Pu depicted a fictional country, Raksasas, where all the inhabitants are freakishly ugly, and social statuses are granted to people according to their looks: the uglier, the higher their status]. Pu challenged conventional standards of beauty and talent in this story, with the purpose of ridding himself of the so-called drive for “social advancement,” which was indeed a social phenomenon of people lost in materialism.

The story “The Mural” illustrates Pu’s idea of “Illusion arises from oneself.” In this story, a man named Zhu Xiaolian visited a monastery where he lingered before an exquisite mural, mesmerized by the image of a smiling maiden with unbound hair. In the next moment, Zhu was transported bodily into the mural itself, and his adventures had just begun: “On the eastern wall, in a painting of the Celestial Maiden scattering flowers, was a girl with her hair in two childish tufts. She was holding a flower and smiling; her cherry lips seemed about to move; her liquid gaze about to flow. Zhu fixed his eyes upon her for a long time until unconsciously his spirit wavered, his will was snatched away, and in a daze, he fell into deep contemplation. Suddenly his body floated up as though he were riding on a cloud, and he went into the wall” (trans. Judith T. Zeitlin). [Although Zhu enjoyed his time with the smiling girl in the painted world, later he was “called” back to the real world by a monk, which indicates the illusory nature of the painted world]. The painted world in this story represents a utopia in the East.

All of the Liaozhai tales mirror reality. Pu’s path through life was hard. Deep indignation rooted in the unfairness of feudal society was a source of inspiration for Pu, who used supernatural beings to express his feelings. However, the supernatural beings themselves were not cruel. Different from the vampiresses in Hollywood films who seduce men in order to drink their blood, most of the fox fairies, female ghosts, and other female fairies in Liaozhai possess kind hearts and a fairylike demeanor. Take the story “Jiaona” as an example. Kong Xueli, a fictional descendent of Confucius, met with a man whose family name was Huangfu, in a run-down house. They soon became good friends. One day, Kong was sick, and Huangfu’s younger sister, Jiaona, came to the house to cure him. After Kong recovered, he married Huangfu’s cousin Songniang. Huangfu and his relatives were not human beings but fox fairies, but Kong was not afraid of them. He still treated Huangfu as his best friend and even saved Jiaona from danger. The last paragraph of this story is Pu’s comment: “What I admire about the scholar Kong is not that he married a beautiful wife, but that he also had a good friend whose countenance could make him forget his hunger and whose voice could bring him joy and delight. To have a good friend like this to talk to and dine and wine with means an interflow and merging in the spiritual realm. Such friendship surpasses carnal love.” This story also reveals that Pu valued spiritual intimacy more than physical intimacy in building relationships.

Shen Dali is a professor from Beijing Foreign Studies University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG