On ethnographic filmmaking in visual anthropology

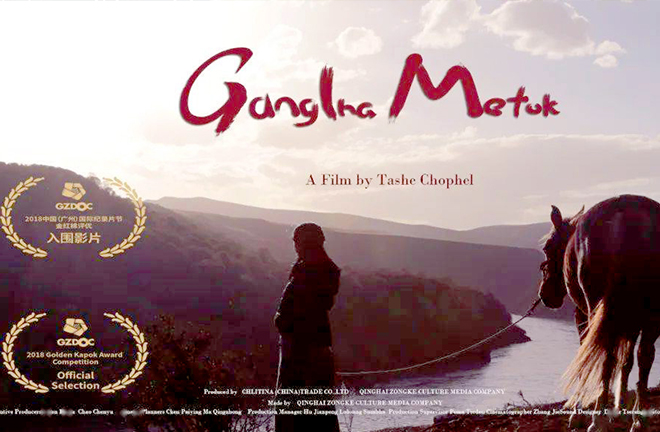

An ethnographic film featuring the life of nomads from Tibetan Plateau Photo: ANTHROPOLOGY MUSEUM OF GUANGXI

It seems that visual anthropology in China has embraced relative prosperity. Institutions and departments dedicated to visual anthropology have been established in many universities, and an increasing number of studies have been conducted in this field. Ethnographic films have been produced and disciplinary seminars taught. Affiliated with the China Union of Anthropology and Ethnological Sciences (CUAES), the Ethnographic Film and Visual Anthropology Committee was specially founded. It can be said that the integral elements of teaching, filmmaking, research, and film screenings have basically been established in the field of Chinese visual anthropology.

Field investigation and observation

The discipline has strong operability and practicality. Film documentation is continuously needed, and in the process of this consistent practice, scholars deepen their understanding of visual anthropology’s underlying theories. With new understanding, reflection usually follows, which can become part of the study, and is conducive to the next filming.

Unfortunately, ethnographic films are often considered uninteresting due to their slow pace and tediously long plots. The films are shot over a long period of time, with much energy spent and great efforts invested, only to encounter harsh criticism upon their release. Definitely, the critiques have a certain logic in them. Ethnographic films still reach only superficial levels of the subject being studied. If a documented wedding ceremony or funeral only pays attention to the process of the ceremony, or a film study of agricultural production activities only pays attention to the natural phenomena of climate and season, as well as knowledge of planting management, then these films linger on the surface. This is why field research prior to on-the-spot shooting is particularly important when shooting a high-quality ethnographic film. Additional observation is also essential for filming. Such observations should occur first during the field investigation process, and then during the filming process. If observations pay scrupulous attention to detail, the film becomes enriched and has a stronger audience appeal.

Overlooking figures

Ethnographic films tend to neglect the personalities and characteristics of individual figures. Take as an example comparisons between documentaries made by professional documentary makers and ethnographic films shot by academics. Documentaries focus specially on the personalities, feelings, and thoughts of certain figures, and convey their impressions of the surrounding world. But ethnographers prefer culture to humans. It is considered paramount for ethnographic films to present and interpret culture, and figures appear in ethnographic films solely in order to present the culture. With such a mindset, the figures become chess pieces that are used to display culture–this is what we should be acutely aware of.

Other ethnographic films overly accentuate visual delight by pursuing a sheer romantic atmosphere rather than setting cultures in a more global background, presenting figures and environments in less glamorous situations which are a consequence of modernization.

Ideal ethnographic films

Filming which obtains recorded materials over a long-time span can be used as video archives to document the local culture, or can be studied as anthropological research materials.

Another reflection in ethnographic filmmaking is whether films should be subordinate to the audience’s taste, satisfying their demands, or whether films should have their own styles. Elements that strike chord with audiences should be explored to cultivate the audience’s taste rather than blindly catering to their film watching habits and cultural literacy. I have deep feelings about this. From 2003 on, we experimented with screening ethnographic films at Yunnan University. Up to today, we have shown about 260 films, which indeed cultivated a group of audience members with good taste.

At last, ethnographic films should focus on innovation, considering interactions with painting, drama, words, imagery, and combining short videos within the films. Only with such experiments, can we see the range of possibilities carried by ethnographic films. When recognizing these possibilities, we will not make these experimental films into ones merely for presentation in film festivals. Since 2000, many of those engaged in rural filming have returned to villages to teach the filmmaking skills to villagers, and invite villagers to make films on their own culture. Discussions from the perspectives of the villagers, scholars, the internal and the external factors have thus arisen.

Chen Xueli is from the Research Center of Ethnic Groups from Southwest Borders and Visual Anthropology Laboratory at Yunnan University.

Edited by BAI LE