Chinese sci-fi grows global audience since 1891

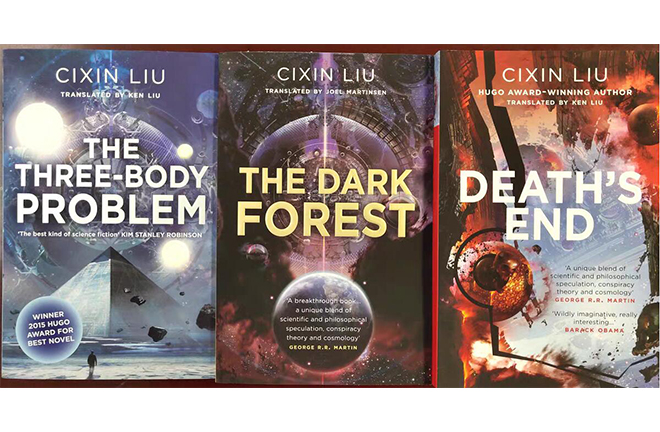

The “Remembrance of Earth’s Past” trilogy by Liu Cixin Photo: FILE

Sci-fi first reached China in the late Qing Dynasty during the mid-19th century, when a collection of Western sci-fi works was translated into Chinese, inspiring Chinese writers to join this new genre. The 100 years which followed witnessed several different patterns of cultural exchange between China and the West.

Made-in-China Sci-fi literature has gone through four stages: prelude (1891–1949), exploration (1950–1966), revival (1976–1999), and expansion (2000–today). Even in its nascent stage, China’s sci-fi literature was preparing to connect to the Western sci-fi market. The endeavor had its first trials in the exploration phase, growth became systematic in the third stage, and it eventually achieved its goals in the development phase.

Translate and imitate

Sci-fi, as an “imported” literature genre, arrived in the mid-1800s, when Western cultures were introduced to China and accepted by Chinese people, the historical period of “eastward dissemination of Western learning.” The first wave of science fiction was among the works translated in China and widely imitated between the mid-1800s and early 1900s. This one-way flow, to a certain extent, reflects the unbalanced position of cultural exchange between China and the West.

During this period, science novels translated into Chinese were instilled with the “saving China through science” ideology. This is shown in “On the Relationship Between Fictions and Governance of the People” (1902), in which political activist Liang Qichao famously wrote “If one intends to renovate the people of a nation, one must first renovate its fiction.” Another case in point is in the prelude that writer Lu Xun wrote in his translation (1903) of Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon: “Leading the Chinese people forward begins with science fiction!”

Science fiction novels translated into Chinese at the time include Liang’s translation (1902) of The Last Days of the Earth and writer Bao Tianxiao’s translation (1905) of Tales of Mr. Absurdity. The heavy influence of these translations on the country’s sci-fi novels can be seen in the titles of some Chinese native-born novels: Liang’s utopian novel The future of New China (1902), Xu Nianci’s New Tales of Mr. Absurdity (1905), Bao’s La Fin du Monde (or The End of the World, 1908), and New China (1910) by Lu Shi’e.

Although the feverish rush to translate foreign science fiction cooled down after the 1920s, Chinese sci-fi literature reached a new height when the works began to be translated into foreign languages. The English version of Lao She’s Cat Country (1932), translated by James Dew, was published in 1964 by the Center for Chinese Studies at University of Michigan, making the novel the first full-length Chinese science fiction to be translated and introduced into the Western world. Retranslated, Cat Country was published by Ohio State University Press in 1970, and later translated into French, German, Japanese, Russian, and Hungarian. This novel marks the debut of Chinese sci-fi literature on the global stage.

Going global

In its second and third development phases, the exploration and revival stages, an increasing number of Chinese sci-fi works were introduced overseas in a systematic way. As more Western publications began to pour into Chinese bookshelves, a two-way translation channel had gradually taken form.

Compiled by Wu Dingbo and Patrick Murphy, Science Fiction from China (1989) was published by Praeger Publishers in New York. The book collected and translated eight important short- or medium-length sci-fi stories from the early 1980s, including “The Death of the World’s First Robot” and “Death Ray on a Coral Island” by Tong Enzheng, “Conjugal Happiness in the Arms of Morpheus” by Wei Yahua, “Reap as You Have Sown” and “Corrosion” by Ye Yonglie, “The Mirror Image of Earth” by Zheng Wenguan, “The Mysterious Wave” by Wang Xiaoda, and “Boundless Love” by Jiang Yunsheng. The collection was the first systematic endeavor to translate Chinese sci-fi into foreign languages. Within a few years, the English version of Shi-Kuo Chang’s full-length science fiction The City Trilogy: Five Jade Disks (1985), Defenders of the Dragon City (1986), and Tale of a Feather (1991), was published by Columbia University Press in 2003.

Entering the 21st century, Chinese sci-fi is now translated into foreign languages in a large scale and systemic way. The imaginary works of Chinese science fiction have gradually penetrated into a deeper level of Western culture. We are now witnessing Chinese sci-fi literature entering the world stage for the second time. At this stage, contemporary writer Liu Cixin’s five full-length novels, one novel collection, and 21 short stories have been translated into about 20 languages, and have been published and sold across the globe. As the winner of multiple awards, Liu’s “Remembrance of Earth’s Past” trilogy has become a phenomenal cultural milestone in Chinese sci-fi’s “journey to the West.” The Three-Body Problem, the first book of the trilogy, won the 2015 Hugo Award for best novel.

Meanwhile, works by other Chinese sci-fi writers have also become well-received overseas. A good example is Invisible Planets, an anthology of Chinese short speculative fiction edited by Ken Liu. The collection includes “The Year of the Rat,” “The Fist of Lijian” and “The Flower of Shazui” by Chen Qiufan, “A Hundred Ghosts Parade Tonight,” “Tongtong’s Summer,” and “Night Journey of the Dragon-Horse” by Xia Jia, “The City of Silence” by Ma Boyong, “Invisible Planets” and “Folding Beijing” by Hao Jingfang, “Call Girl” by Tang Fei, “Grave of the Fireflies” by Cheng Jingbo, and “The Circle” and “Taking Care of God” by Liu Cixin.

What’s more, sci-fi translation and modes of spreading Chinese sci-fi overseas have both become increasingly specialized, with patrons like Chinese official institutions playing a big role in supporting the translation of Chinese sci-fi, making it a strategic move to build the country’s cultural presence in the world.

Imagined future

Science fiction, as a futuristic literature genre, is a carrier of human imagination. For over a century, Chinese sci-fi has steadily increased its popularity among Western readers, which is meaningful in the following ways.

First, from one-way inspiration in late the Qing dynasty in mid-19th century to two-way exchange in a globalized world, sci-fi has come a long way in China. The process reflects the evolution of cultural communication between China and the West. There has been a shift from the eastward dissemination of Western learning to the communication and interaction between different cultures in a diversified world.

In the late Qing Dynasty, pioneering intellectuals began to translate Western sci-fi works into Chinese, aiming to enlighten the people and invigorate the country. These Western novels triggered what American historian John King Fairbank called “impact and response.” Almost overnight, all that belonged to the West was considered “advanced” and “civilized.”

After a century of development, more Chinese science fiction is published and distributed in the West. This process coincides with the evolving mode of cultural exchange between China and Western countries, moving from one-way dissemination to two-way dialogue.

Second, this process also indicates that learning from the West helps China tap its potential. In turn, China can also inspire the West and fuel global knowledge production and theoretical innovations. By contributing to world literature, Chinese literature can become a driving force for innovation throughout the world.

Third, by developing Chinese sci-fi creation and studies, and by engaging in a dialogue with world literature that is traditionally dominated by Europe, China is able to break the pattern of Western-centrism and help diversify world literature.

Sci-fi should feature diversity and openness. However, as Chen Qiufan pointed out, for too long, our imagination of the future world has been defined by sci-fi movies like Hollywood blockbusters. These works are projections of values and ideologies from a unipolar world.

Although Liu Cixin’s works and film adaptations are well-received, it is necessary to acknowledge that a wide gap remains between China’s ability to create sci-fi and adapt it into films, as well as talent training. For instance, after the successful screening of Wandering Earth, another Chinese sci-fi novel Shanghai Fortress failed to live up to people’s expectations when it hit theaters in 2019. This shows that the Chinese sci-fi industry still has a long way to go, and the ten measures recently released by the Chinese government for guiding development of the sci-fi industry are highly relevant and visionary.

In this globalized world, imagination has become cultural soft power. One day, fighting to define a vision of the future may become a new battlefield among major countries.

Wu You is from the School of Foreign Languages at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Edited by WENG RONG