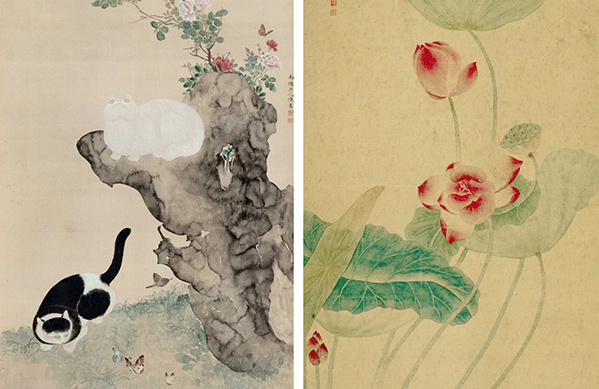

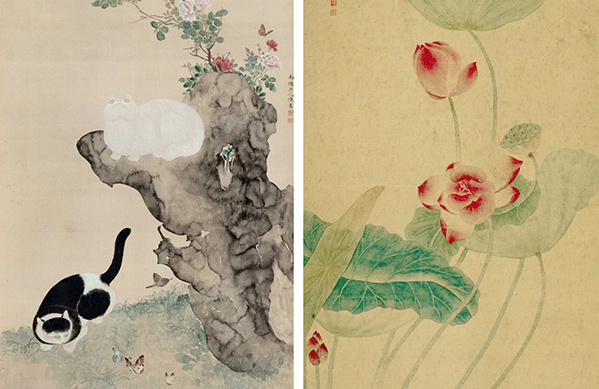

"Cats and Butterflies" (left) by the Qing female artist Chen Shu, and "Autumn Colors in a Lotus Pond" (right) by the Qing female artist Yun Bing Photo: FILE

Economic issues have been an important topic in the study of women's history. Plenty of research has been conducted on women's involvement in agriculture during the Qing Dynasty (1644―1911). In recent years, publications of a large quantity of literary works or documents about women make it possible to study the ways that educated women made a living during the Qing Dynasty. This study not only complements women's history research and the economic history of the Qing Dynasty, but also sheds light on the relationships between women and families, clans and society in the Qing era.

There were more than 4,000 educated women recorded during the Qing period, most of whom had to seek a living to support their families. They made significant contributions to household incomes. The majority of these women earned a living with skilled manual labor—traditional needlework—or intellectual works. Intellectual works often included painting or teaching young girls as guishushi, literally translated as teachers of the inner chambers, a class of itinerant women who made a living by teaching girls in elite households the classics, the art of poetry, and painting.

The term nyugong refers to the needlework that all women were required to learn in ancient China. Due to the population boom and the abundance of intellectuals who were in competition for imperial examinations during the Qing Dynasty, middle-and-lower-class intellectuals usually lived under great economic pressure. Many literate women married these intellectuals. These women struggled to make a living and had to become the breadwinners of their families.

The nyugong of the Qing era included assorted artistic skills. Weaving and embroidery were the most widely applied skills. Other skills, such as making velvet flowers, or ronghua, and making flowers out of rice-paper plants, were more poorly paid and the labor was much harder. A diligent woman could feed two or three people through her needlework. However, the cost of taking care of elder family members and raising children, paying for clothing, medicine, and the children's education, could be considerably expensive. A women’s needlework was barely sufficient to support her family.

In addition to needlework, these well-educated women had another choice—to become "teachers of the inner chambers." There were four types of women who might become teachers. The first and largest group was chaste widows and those who decided to remain single. They had to support themselves, and sometimes their children and aged people in the family. The second classification of women are those who married poor men. They had to work to make ends meet. In addition, women who struggled to survive during times of war and those rebuilding their lives after abusive relationships also wanted to financially support themselves and worked as teachers. Teaching was often the only choice for women in extremely difficult circumstances.

Between the Ming (1368―1644) and Qing dynasties, Wang Duanshu (1621―1701) and Huang Yuanjie (c. 1620―1669), two women who were born in literati families in Zhejiang Province, pioneered the career of working as private tutors. Both of these women lost their homes during the troubled times of the late Ming Dynasty. Their husbands failed to support their families.

Teaching girls in elite families became the only way to survive. Traveling around places where different students lived, Wang and Huang had a difficult time. They didn't simply suffer from poverty and danger, but were also exposed to public contempt and scandal. Huang's son drowned when she was sailing toward present-day Beijing to teach an official's daughter, and her own daughter died of illness the next year. Despite their hard lives, Wang and Huang gained reputations for their literary achievements and artistic talents in the intellectual circle, and illustrated a broadening of possibilities for independent women during the Qing Dynasty.

Qing-Dynasty archival documents have records of numerous female teachers. The public gradually accepted women's role in society and praised them for their independence. Many female teachers opened up their own "family schools," and some of them even became celebrities and were widely admired by literati and ladies of noble birth. Through their careers, female teachers worked for more than bread and butter. The prestige associated with teaching is described by Dorothy Y Ko in Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China, "As spiritual descendants of the most revered woman scholars in the Confucian tradition, teachers of the inner chambers acquired an unassailable mantle of respectability." Different from the early female teachers, who were held in contempt by the public, such as Wang Duanshu and Huang Yuanjie, the teachers of the inner chambers who appeared later were accepted. This type of work was justified as an ordinary profession for women. They were often compared to the Han-Dynasty female historian-teacher Ban Zhao, and were viewed as the Confucian promoters and inheritors of the tradition of woman’s learning.

During the Qing Dynasty, female artists earned a living by selling their paintings. Compared with teachers of the inner chambers, female artists usually didn't have to travel, so they were not as influenced by public opinion. Some female artists also worked as the teachers in the inner chamber. Some became famous artists, and people were willing to spend great sums of money on their paintings, such as the artists Yun Bing and Ma Quan, from present-day Jiangsu Province. However, most female artists didn't rise to fame, and they worked hard to earn a living selling their works.

Li Yin (1610―1685) and Huang Yuanjie were the representative female artists between the Ming and Qing dynasties. Living in a time of turbulence and disorder, however, they didn't earn much selling their paintings. The works of the female artist Chen Shu (1660―1736) were favored by Qianlong Emperor and many of her works were featured in the imperial collection. Apart from her artistic works, she was also known as the mother of Qing statesman and poet Qian Chenqun. Chen was adept at all genres of traditional Chinese painting. She painted figures, landscapes, and flower-and-bird paintings. At the beginning, Chen sold her paintings for low prices. In order to support her family, she had to paint every day, and the following day her servants would bring her fresh paintings to a larger town, over 10 km away, to market the works of art.

Some female artists also had to sell the paintings themselves. For example, Shen Shanbao (1808―1862), a female artist born in Zhejiang Province, lost her father at an early age. At age 16, Shen started to sell her paintings to feed her mother and younger brother. Some of her poems provided biographical material on how she traveled around to sell paintings in 1832: She left Hangzhou on the tenth day of the eighth lunar month, spent several months travelling through Changzhou, Jiangdu, Gaoyou, and finally arrived at Huaian. After selling all her paintings, she would return home. What drove her to Huaian in spite of the distance, was that this city was a water transport hub at that time. Many dignitaries lived in this city, meaning there was a large market for paintings. Shen was a productive painter. She even painted on the boat when sailing down the river.

Born in lower-and-middle-class literati families, living in poverty, most learned women during the Qing Dynasty had to earn a living to support their families. In addition to needlework, they were well-educated and innovative, and were able to transform their literary or artistic talents into economic assets to improve their livelihoods. Women's improving economic well-being changed their status in their families. Sometimes, they could make key family decisions or were even recorded as important figures in the family history.

Gu Shengqin is from the School of Communication at Soochow University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG