On developing semiotics with Chinese characteristics

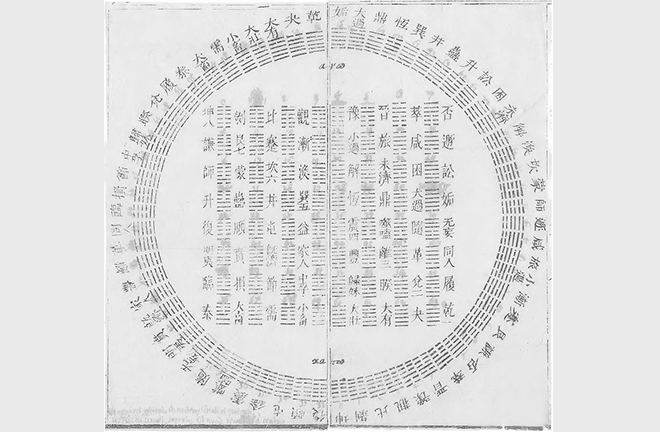

A diagram of I Ching hexagrams. Each hexagram has its own particular meaning in divination, and the lines represent yin and yang, the basic polarities of Chinese cosmology and philosophy. Photo: FILE

Semiotics came into being in the early 20th century, when Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles Sanders Peirce each established theories with completely different models and systems. In the 1960s, Saussure's semiotics became a famous discipline as structuralism thrived. However, as post-structuralism emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, Peirce's theory gradually replaced Saussure's to become the foundation of contemporary semiotics.

To date, many systems and schools have been developed in Western semiotics. In comparison, China only started developing its own semiotic studies in the 1980s. Nevertheless, China's semiotics has developed rapidly, research has made great progress both in the quantity and quality of work in the field. As the country grows stronger economically and technologically, and as China's global status improves, Chinese semioticians must catch up both by bringing in other countries' work and prioritizing localization. We must grow a school of our own out of China's cultural soil, which offers us much to draw upon.

Conceptual system

When developing a theory, the primary task is to define its basic elements. In essence, this begins by establishing a core conceptual system for the theory. The "sign" is the core concept of semiotics. To build semiotics with Chinese characteristics, we must start with the core concept by interpreting the structure and classification of signs, defining semiotics, its status and functions, as well as its relationship with other disciplines.

To study semiotics, we must first properly define "signs." Chinese scholars have not probed deeply into this matter. Instead, most of them readily accepted Saussure and Peirce's concept of signs. The process of forming a core concept holds dialectical unity between the mind (on the inside) and the material world (on the outside). Humans visualize, conceptualize, and categorize objects and phenomena we see in our day-to-day life, and later turn them into abstract symbols that can be filed in our minds. Signs weave people's daily lives and experiences into an infinitely well-connected network, where they function as the nodes linking all fields of our lives together in an organic way.

A system of core concepts is an important starting point, from this point scholars can construct a scientific and independent academic theory. It also lays the foundation for new concepts to be derived, constructing systems and models for these novel concepts. A system of core concepts with Chinese characteristics can offer new epistemologies and methodologies for developing China's semiotic studies. It might even be able to showcase a brand new view of the world.

A system of core concepts is the backbone of an academic theory. It determines a theory's boundary of application. It also becomes a source of vitality and creativity for theory construction. To set up a core conceptual system is the primary task when developing Chinese semiotics. Scholars must abide by a series of scientific principles to ensure that the conceptual system is systematic, patternized, categorizational, predictive, and standard. Semiotics, as a condensed summary of humanities and social sciences, is highly relevant with many disciplines. Chinese semiotics must be built on core concepts that are systematic, interlinked, and can be developed into a complete conceptual system.

Foreign and local combined

In the early 1980s, Chinese scholars started to introduce and translate the works of theory schools from other countries, including the main theories of Ferdinand de Saussure, Charles Sanders Peirce, Umberto Eco, Roland Barthes, Mikhail Bakhtin, and Yuri Lotman. Decades on, as more and more translations have been published, Chinese scholars have gradually begun independent or comparative studies on these works. These studies mainly focus on introducing and interpreting foreign theories in a systemic way. One after another, China has brought in the following theories: Saussure's theory of language as a semiotic system, Peirce's conception of a triadic sign relation and classes of signs, Eco's theory of codes and sign production, Bakhtin's dialogism, Lotman's modeling system of symbols and semiosphere, Julia Kristeva’s intertextuality and semianalysis, as well as A.J. Greimas's narrative semiotics.

Among them, Saussure's concept of linguistic signs has had the biggest influence among Chinese semiotic researchers. It has become the center of semiotic studies in China. Chinese semioticians have gained remarkable results studying Saussure’s theories, and have published many a thesis discussing the nature and functions of linguistic signs, code-switching, nominatum, and markedness.

In studying semiotics in art and culture, Chinese scholars have brought in, translated, and meaningfully probed theories such as Bakhtin's polyphony and carnivalization, along with Lotman's concept of text, the semiotics of culture, and modelling systems. At the same time, Chinese scholars have also begun to study semiotics in film, semiotics of architecture, media semiotics, semiotics of non-verbal communication, and crossover studies of AI and semiotics.

Currently, semiotic studies are thriving. While scholars continue to bring in advanced theories from other countries, Chinese scholars also need to localize what we have learned from others, and combine theories both from the West and the East. Bearing this in mind, we need to conduct thorough and in-depth studies from the following perspectives: the definition of signs and core concepts, signifying practices, the construction of general theories, discipline construction, semiotics for specific industries, interdisciplinary integration study, and applied semiotics.

We must balance assimilation and localization. The study of semiotics in China can date back to ancient times. The logic of semiotics has long been incorporated in ancient scholars' academic thinking. Ancient Chinese exploration of semiotics can be found in Gong Sunlong (320 –250 BCE)'s Ming Shi Lun (On Name and Substance), Xunzi (c. 316–c. 235 BCE) and Han Fei (c. 280–233 BCE) on rectifying names (zheng ming), the trigrams in Yi Jing (or Book of Changes), Yin Wen (c. 360–280 BCE)'s semiotic determinism and analysis of functions of signs, Hui Shi (c. 370–310 BCE)'s Ten Paradoxical Propositions, Laozi and Zhuangzi (369– 286 BCE)'s concept of "the names that cannot be named" (wu ming) and "nondoing" (wu wei), and Mohism's philosophy of logic. There are many outstanding ancient works on semiotics, such as The Argument of Indication and Substance, On Name and Substance, and Rectifying Names, to name but a few. Discussions of semiotics can also be found in Daxue (The Great Thinking) in Liji (The Book of Rites), Shiyan (Explaining Words) in dictionaries Erya and Guangya, as well as pre-Qin thinkers' quotations. These are all valuable assets for Chinese semiotic researchers to start with.

Chinese semiotic studies has a profound history, and Chinese culture has all the components needed to bring vitality to Chinese semiotics. Scholars must further explore and categorize traditional Chinese classics within history and culture, and conduct a well-rounded study of Chinese semiotics' development process, so as to sort out the features, research methods, and achievements unique to each development stage. We must also see the potential of studying Chinese writing systems, which have witnessed society's changes and people's changing lives in ancient China. Chinese characters are symbols themselves.

Strengthen weak links

Currently, Chinese scholars mainly focus on the following work: following, incorporating, and translating excellent semiotic theories from other countries; explaining and arranging established semiotic theories from other countries. Linguistic signs based on Saussure's theories continue to appeal to scholars as a hot research topic. Some have also traced semiotic resources from ancient classics. Semiotics has become a new methodology and cognitive tool that is widely applied to many disciplinary studies.

Despite our achievements, Chinese semiotic studies needs to strengthen the following weak links. First, semioticians focus too much on explaining overseas theories and too little on local studies. We need to increase construction of semiotics with Chinese characteristics. Second, we need to construct general semiotics and sectoral semiotics. Third, too few research directions have been explored, while semiotics in literature, culture, art, general narratology, film, and non-verbal communications have not received the attention they deserve. Studies of these directions lag far behind those of linguistic semiotics. Fourth, when applied to other fields of research, semiotics often comes as a tool for analysis. It often functions more like a methodology than a scientific theory. Fifth, our studies and interpretations of classic semiotics remain in the initial stage, and fail to fully integrate with the advanced studies in the broader academic world. Sixth, we have a lack of input in disciplinary construction, talent cultivation, platforms for academic discussions, and more. Semiotics lacks presence in scientific and research institutes' curricula, and more teaching resources need to be distributed within institutions.

To address these issues, we can start with the tasks below. We must incorporate our own strengths, prioritize original research results, and conduct critical analysis of the existing semiotic theories. We need to build a core concept system for Chinese semiotics, expand new frontiers, and strive to take the lead when identifying and filling gaps. We also need to improve the research pattern of semiotics, carry out diversified research and guide the infiltration of semiotics into disciplines outside linguistics, so as to produce new crossover disciplines and enrich the system of semiotics. In addition, we must enhance discussions of fundamental theories, and draw lessons from the applications of semiotic methodologies in other fields. We need to improve the disciplinary system of semiotics, build research foundations, and let outstanding semiotic researchers play a leading role in the discipline. Meanwhile, we must increase input in cultivating interdisciplinary talent, and integrate academic resources from linguistics, logic, philosophy, cultural studies, literature and art, AI, and media. We also need to dig further into the material data and documents from ancient China for semiotic elements and history, trace the development of ancient. Last but not least, we must find opportunities to carry out academic dialogues with the international semiotic researchers, so as to introduce China's semiotic theories into the global arena, and improve Chinese scholars' academic influence.

Wang Lei is from the Center for Russian Language Literature and Culture Studies at Heilongjiang University.

Edited by WENG RONG