Early interpretations of ‘society’ from Lu Xun’s novels

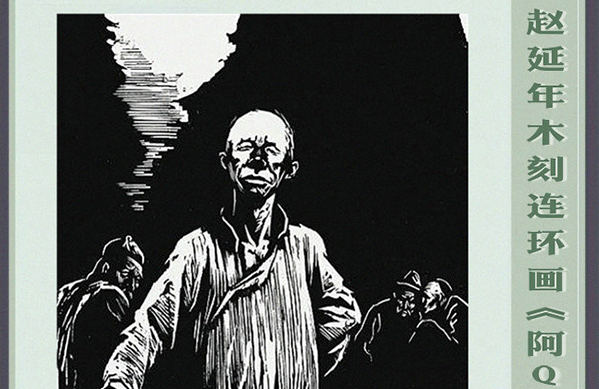

A woodcut illustration of The True Story of Ah Q by the artist Zhao Yannian depicts how Ah Q shows off his coppers and “a large purse.” Photo:FILE

The term 社会 (shehui) appeared as the translation of society in China during the late 19th century. According to the Chinese sociologist Li Qiang, Japanese scholars first translated the term “society” into the term shehui, which was in turn adopted by the Chinese scholars when they translated Japanese works.

However, the Chinese scholar Yan Fu (1854–1921) chose the term 群 (qun, literally meaning “group”) instead of shehui to represent “society” when translating The Study of Sociology by Herbert Spencer, and he translated the title of the book into 群学肄言 (Qunxue Yiyan). Yan Fu had already known the Japanese translation of society, and he frequently used the term shehui when interpreting qunxue (sociology), but he chose qun to represent society because of his respect for traditions and the idea that learning should contribute to good governance.

As one of the most influential Chinese writers of the 20th century, Lu Xun (1881–1936) witnessed the profound transformation between the late 19th century and the early 20th century. His works, particularly novels, tend to depict the life of ordinary people at that time, thereby revealing the general situation of the era. The concepts of shehui mentioned in Lu Xun’s works provide an opportunity for readers to understand how China’s “society” took shape and evolved.

In Na Han (Call to Arms) and Pang Huang (Wandering), two collections of stories written by Lu Xun between 1918 and 1925, the meaning of shehui continued to change with time.

‘Shehui’ not equal to ‘society’

“Kuangren Riji” (“Diary of a Madman”) is Lu Xun’s first novel written in vernacular Chinese in April 1918. The term shehui first appeared in his short story “Toufa de Gushi”(“The Story of Hair”), which was written in Oct. 1920. At that time, shehui was not clearly defined and it hadn’t shown real social significance yet. The reason was hidden behind the social context of the time.

In a letter about a debate on translation to Qu Qiubai (1899–1935), another important literary figure of 20th-century China, Lu Xun mentioned the term qun as Yan Fu’s translation of society. However, he didn’t adopt this term in his own works. It might have something to do with his early years as a student in Japan and the fact that the new words created by Yan Fu during translation failed to compete with the Japanese-created words. When interpreting the term society, many Chinese scholars, including Lu Xun, were inevitably influenced by translators. Furthermore, China between the late 19th century and the early 20th century was still dominated by the social structure known as Chaxu Geju, a differential mode of association, a concept that Chinese social relations work through social networks of personal relations with the self at the center and decreasing closeness as one moves out, put forward by the pioneering Chinese sociologist and anthropologist Fei Xiaotong (Fei Hsiao-Tung). Therefore, it was difficult for scholars to understand the nature of “society” at that time.

“They were scorned, mocked and persecuted by people [shehui] all their lives; now their graves, forgotten in time, slowly lapsed into ruin.” “It’s hard to know how many people have been abused by other people [shehui] throughout their lives because of their shaven heads.” These two sentences which mention the term shehui are derived from “The Story of Hair.” The former signifies the young people who died for the Wuchang Uprising against the ruling Qing Dynasty that took place in Hubei Province on 10 October 1911, while the later is about the people who were sentenced to a punishment known as Fa Xing (head shaving) in ancient China. Here the term shehui is equal to “people” rather than the “society” in modern context.

‘Shehui’ as ‘community’

In the novella The True Story of Ah Q written in 1921, Lu Xun mentioned the term shehui again: “…with the result that the villagers [shehui] had had no means of knowing it” (trans. William A. Lyell). In this story, the term shehui is similar to Ferdinand Tönnies’s Gemeinschaft, which is often translated as community.

“Weichuang [a small village where the story happens] was not a big place, and soon he had left it behind.” It indicates that the fictional Weichuang is viewed as “a place situated in a given geographical area” and “shared by a community” (see Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft by Ferdinand Tönnies). People in Weichuang have simple and direct face-to-face relations with each other, exemplified by Ah Q’s acquaintance with all the villagers of Weichuang. Furthermore, people in Weichuang are regulated by common norms or beliefs. For example, Ah Q was once “favored with a slap on the face” by Mr. Chao, a rich and famous senior villager, because he claimed that his surname was Chao and thus is related to the Chao family. After the incident, everybody “seemed to pay him unusual respect.” Lu Xun explained in the story that “In Weichuang, as a rule, if Li So-and-so hit Chang So-and-so, it was not taken seriously. A beating had to be connected with some important personage like Mr. Chao before the villagers thought it worth talking about. But once they thought it worth talking about, since the beater was famous, the one beaten enjoyed some of his reflected fame.” On one day, Ah Q returned from the town, walked into a wine shop, and “pulled a handful of silver and coppers from his belt.” “He was wearing a new, lined jacket, and evidently a large purse hung at his waist, the great weight of which caused his belt to sag in a sharp curve. The other villagers reacted in the same manner, “It was the custom in Weichuang that when there seemed to be something unusual about anyone, he should be treated with respect rather than insolence, and now, although they knew quite well that this was Ah Q, still he was very different from the Ah Q of the ragged coat…and so the waiter, innkeeper, customers and passers-by, all quite naturally expressed a kind of suspicion mingled with respect.”

In this sense, the fictional Xianheng Restaurant from Lu Xun’s short story “Kong Yiji”, the hometown from “My Old Home” and the teahouse from “Medicine” share some similarities of community.

‘Shehui’ as ‘society’

The reason why “society” had been absent from China for thousands of years lies in the absence of “public sphere” or “public space” since ancient times. People in ancient China were united by ties of family (kinship), with a universal sense of solidarity within each family or lineage. Outside the families, public sphere and public space had long been ignored. The social structure of China formed in this way was characterized by relying on the ties of family (kinship) more than collective actions based on non-biological relations.

Lu Xun’s works written between 1922 and 1925 show the signs of “the public” and “market”, and the term shehui started to reveal the nature of modern “society.” In the short story “Duanwu Jie” (“Dragon Boat Festival”) written in June 1922, the main character Fang Xuanchuo is a teacher as well as a civil servant. His favorite phrase is “more or less the same.” Influenced by his career and “more-or-lessism,” he considers himself “a stoically law-abiding sort of person, the kind that refuses to take part in any kind of public protest.” This personal philosophy takes him away from the teachers’ union, even if he is short of money. Different from China’s traditional organizations which heavily rely on kinship tightness, the members of the teachers’ union are organized as individuals with the common purpose of “publicly demonstrating for the money they were owed.” The advent of non-governmental organizations that are independent of families and lineages is one of the characteristics of modern “society.”

As a word imported under a certain historical context, the nature and concept of “shehui” is still evolving. In sociological studies, the awareness of finding the truth from history and reality helps understand the past and the future of “shehui.”

Zhu Anxin is an associate professor from the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Nanjing University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG