Modern gender culture key to ecological conservation

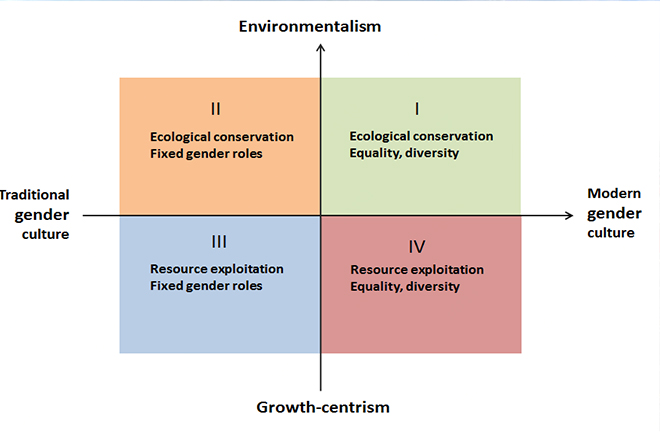

The above four quadrants reflect the relationship between gender cultures and environmental attitudes. Photo: Chen Mirong/CSST

Disseminating China’s ideological framework shengtai wenming, or ecological civilization, will expand the social base for ecological conservation and enhance public participation in environmental protection across the nation. While prioritizing environmental education and publicity, it is essential to build an eco-friendly social culture which creates conditions for the public to understand, accept, and practice the ideas of ecological civilization. Particular attention should be paid to the impact of gender norms and gender culture on environmental attitudes.

Relevance

In public domains, women normally show little interest in public issues as compared to men, but they have exhibited a tremendous enthusiasm for environmental topics.

In 1962, American ecologist Rachel Carson brought public attention to the irreversible environmental damage caused by pesticides, setting off a wave of environmental protection initiatives around the world.

Over more than a half century later, environmental action has continued in different countries and regions, where women organized and participated in many major environmental events.

In 1973, for instance, women in the Himalayan region of Uttar Pradesh, India, initiated the Chipko Movement, in an effort to prevent deforestation.

In 1977, Kenyan female social activist Wangari Maathai launched the “Green Belt Movement,” mobilizing local impoverished women to take part in tree planting and water harvesting, reshaping ecosystems in Kenya and starting a pan-African “Green Belt” initiative.

In 1996, Chinese female environmentalist Liao Xiaoyi founded the “Global Village of Beijing” in the capital of China, which has since been committed to public environmental education.

Starting from 2018, Swedish activist Greta Thunberg has been calling for global attention to climate change by boycotting classes. She has since expanded her efforts, advancing international cooperation to mitigate climate change.

Compared to other topics, environmental issues have received more attention from women.

Scholars have also noticed the special relationship between gender and environmental issues. Ecofeminism, which emerged in the 1970s, contends that post-industrial social production exploits natural resources to advance human development, making environmental degradation a consequence of economic growth and adding pressure to human survival and development.

At the same time, due to modern division of labor necessitated by industrial production, the perceived impact of environmental deterioration varies between men and women.

As women are generally involved in service-related work with low economic returns or assume such family roles as childrearing and housekeeping, they are more vulnerable to environmental degradation.

Thus scholars argue that environmental problems and gender inequality share the same social roots and neither can be solved alone, urging simultaneous environmental improvement and gender culture adjustment.

In addition, in the field of environmental sociology, researchers have empirically analyzed the relationship between gender and environmental attitudes. Using different measurement tools and based on survey data across time, regions and groups for nearly half a century, environmental sociologists all over the world have arrived at a rather reliable conclusion: environmental attitudes differ markedly between the two genders, and women have given more attention and support to environmental issues and protection than men.

The discovery has been dubbed as a “gender hypothesis” on environmental attitudes, which confirms the correlation between gender and attitudes toward the environment from empirical perspectives.

Social culture vital

In light of the gender hypothesis, environmental sociologists proposed two explanatory clues: gender socialization and social gender structure. By gender socialization, it means that the process of socialization endows individuals with gender qualities according to their physiologic gender. Hence feminine social norms such as being kindhearted and caring, if extended to environmental attitudes, increase women’s attention to environmental changes and protection. Social gender structures stress the social status of men and women alongside the impact of gender identities on environmental attitudes.

Overall, women are comparatively disadvantaged to men in terms of income. Moreover, their social roles, taking care of families and bringing up children, have led them to observe more negative environmental impacts and worry more about their families’ health and safety, so it is easier for them to advocate for environmental protection and hold environmentally friendly attitudes.

On the basis of the two explanatory threads, researchers have invented large numbers of indicators to examine. Regrettably, existing studies have provided very limited empirical support for the above explanations. Most indicators have yet to be backed up by empirical research.

Why are empirical studies capable of determining the significant impact of gender on environmental attitudes, but unable to effectively explain the reason for the impact? A review of and reflections on previous studies reveal that most of the studies consider gender simply as binary and fixed physiological features, ignoring modern social cultural characteristics of gender as well as the diversity and complexity inherent in the physiological sexes.

Gender has rich connotations if interpreted through cultural lens. It is complicated and diverse. Cultural understandings of gender differences vary greatly, and often conflict with each other. For example, some cultures encourage men to be breadwinners and charge women with domestic affairs, maintaining that physiological genders would necessarily result in differences in the division of labor. Others regard males and females as independent individuals with equal social rights and responsibilities, so the social division of labor should not be restricted by differences in physiological gender. Other cultures argue that gender is not the key identifying feature for individuals, refusing to distinguish them by gender and proposing raising children asexually.

Subject to the influence of different cultures, individuals’ understandings of gender differences and relations have diversified and might change according to region and time.

Measuring gender from cultural perspectives can help capture gender differences between individuals more precisely, thereby broadening our insights into the relationship between gender and environmental attitudes. This assumption was verified in a recent Renmin University sociological survey study that sampled university students in Beijing.

The study randomly chose 1,417 undergraduates at school to measure gender attributes such as opinion on gender roles, attitudes toward gender equality and daily representations of gender qualities, while analyzing the impact of these measured factors on ecological outlooks, cognition of environmental risks and eco-friendly behaviors of the samples, through structural equation models.

According to the analysis, diversified and continuous gender characteristics interpreted from cultural perspectives can explain changes to each individual’s ecological outlook, cognition and behaviors, and support the two explanatory paths of gender socialization and social gender structure to a greater extent than the binary physiological gender conception.

The second result is that individuals more supportive of non-fixed gender roles, equal gender relations and diverse gender qualities are more inclined to stand for environmental protection and frequently implement eco-friendly behaviors. On these grounds, we found that equality-based, diversified and non-fixed gender conceptions are significantly and positively correlated with attitudes and behaviors in favor of environmental protection.

Modern gender culture

From the angle of social culture, modern gender cultures that uphold equal and diversified gender concepts and the awareness of environmental protection, or environmentalism, are different cultural subsystems. They manifest two patterns of cultural trends developed in the 20th century. Both are based on post-materialism, advocate for equality and pursue self-realization.

To visualize the study, gender cultures and environmental attitudes are regarded as continuous variables and marked in the coordinate axes. The relationship between the two can be constructed in a two-dimensional coordinate plane. For the gender culture coordinate, the binary, fixed traditional gender culture is put at one end of the axis and the equality-based, diversified modern gender culture is at the other end. Along the axis of environmental attitudes, growth-centrism (which champions the exploitation of natural resources) and environmentalism (which calls for respect for nature and ecological conservation) are at the two ends of the spectrum.

Therefore, the relationship between gender cultures and environmental attitudes will be reflected in the four quadrants. The first quadrant is represented by modern gender cultures and consciousness for environmental protection, and the third quadrant by traditional gender cultures and growth-centrism. The two factors in each of the two quadrants have the same value orientation. They promote or integrate each other, developing jointly.

On the contrary, traditional gender cultures and environmentalism in the second quadrant and modern gender cultures and growth-centrism in the fourth are both in opposite value orientations. The two factors suppress or compete with each other, thus impeding the development of one another.

The blended and coordinated development of modern gender cultures and environmentalism constitutes a foundation for disseminating ecological conservation philosophies. Traditional gender cultures tend to negate the value of environmental protection and hinder the public from learning, embracing and practicing philosophies related to the ecological civilization. By contrast, modern gender cultures support and affirm ecological conservation, substantively facilitating the construction of an eco-friendly culture for public realization of a national ecological civilization. Efforts thus should be made to create a modern gender culture that fits eco-friendly principles, in order to universalize ecological civilization concepts in more depth across society.

Sun Ying is from the School of Sociology and Population Studies at Renmin University of China.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG