Interdisciplinary studies are the way of the future

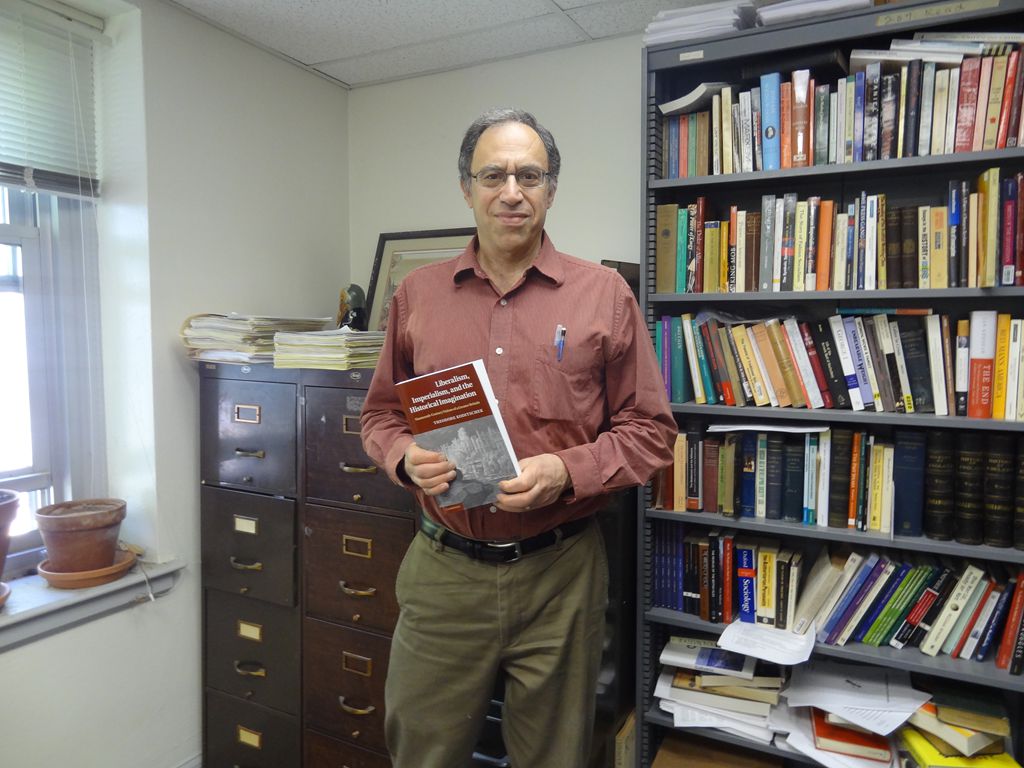

Theodore Koditschek

Theodore Koditschek presenting a Human Science Sequence Award at the ceremony of the University of Missouri in 2012

Theodore Koditschek is a professor of the History Department at the University of Missouri specializing in the field of social history of modern Britain and the British Empire history. He has been chair of the University Library Committee and serves on the editorial board of the International Journal of Regional and Local History. His representative works include Class Formation in Urban Industrial Society: Bradford, 1750-1850 and Liberalism, Imperialism and the Historical Imagination: Nineteenth Century Visions of a Greater Britain.

Professor Theodore Koditschek is a distinguished researcher in the area of modern British social and imperial history. He has published numerous works and articles that have exerted a profound influence on British studies. Recently, Zhang Jin visited Theodore Koditschek at MU to discuss issues in British and American history.

Zhang Jin: As a second generation of Austrian immigrants and a Jewish historian, what inspired you to devote yourself to the study of British history and why did you specialize in social history?

Theodore Koditschek: When I turned 16, my father gave me a copy of Bertrand Russell’s autobiography. My father was a silent man, who never spoke of his prewar Austrian past. All I knew was that he had been some sort of Marxist and that he had also been interested in the Vienna Circle of logical positivists. That summer, I also read Marx’s Capital, volume I, which, of course, builds much of its theoretical framework on an empirical study of the British industrial revolution. These two books were the first to get me interested in British history, but I still had no thought of studying it myself.

In my first year of college, I read J.S. Mill’s On Liberty and saw it as an important precursor of Russell’s thought: another dose of British material, but that isn’t what interested me at the time. On the contrary, I was inspired with high-flown theoretical aspirations. I saw that what was missing from Mill was Marx’s critique of capitalism, and what was missing from Marx was Mill’s defense of liberty. I considered a range of social science disciplines: Sociology seemed too conservative; anthropology demanded qualities of extroversion and physical fortitude that I did not possess. By process of elimination only history and geography were left. Was there any way that history could be turned into something more than a jumble of names and dates, perhaps supplemented by the rivers, mountains and cities where they had transpired? Could history be studied in a manner that drew on my interests in Marxism and philosophy?

In my 3rd undergraduate year, I discovered the answer was ‘yes’ by reading one book: E.P. Thomson’s Making of the English Working Class. It was exciting, filled with pathos and drama. It showed that Marxist history could be written from the perspective of acting subjects.

Unexpectedly, I found myself struck by the power of demographic analysis – how a comprehensive study of something as simple as births, deaths and marriages could provide a point of entry into understanding some of the most fundamental structures of any given social order, and how these structures changed over time. So, I had finally found my metier. I applied for graduate school and never looked back.

Zhang Jin: Is there any special meaning of liberalism that you want to convey in your latest book Liberalism, Imperialism and the Historical Imagination:Nineteenth-Century Visions of a Greater Britain?

Theodore Koditschek: Liberalism is the connecting thread between my first and second books. Both reflect an interest in British bourgeois liberal hegemony, and the different ways that it was practiced both at home and in the Empire. To me, the contradictions of liberalism are among the most pressing and illuminating issues of our time. That story has its origins in nineteenth century Britain.

Zhang Jin: As a historian, you expanded your research into sociological and scientific research. What’s your take on interdisciplinary studies?

Theodore Koditschek: As you have already seen, I’m very favorably disposed towards inter-disciplinary perspectives. This puts me in a small minority in the MU History Department. Fortunately, I have good friends in other units on campus. Like it or not, I think that interdisciplinary studies are the way of the future. In the U.S., the historical profession has been very slow to take up the challenge of inter-disciplinarity. This is short-sighted, and leaves us vulnerable to becoming irrelevant, as archeology, paleo-biology, evolutionary biology, sociology and economics all develop alternate ways of studying the past. Perhaps in China, you can avoid the mistakes that we have made.

Zhang Jin: In Thucydides’ masterpiece History of the Peloponnesian War, leader Pericles spoke highly of the patriotism of the Athens state funeral ceremony. How would Americans respond to Pericles’s Funeral Oration today?

Theodore Koditschek: Modern American democracy and ancient Athenian democracy are in some ways similar, and in other ways dissimilar. I think that the reaction in this country, during the days immediately after 9/11, demonstrated that U.S. citizens are capable of putting aside our differences and selfish interests. We are capable of rallying together to defend ourselves at such moments when our borders and way of life are directly, actually threatened.

In my case, I hope that I’d fight to protect my right to make statements like the ones below that are critical of my own government. However, I believe that, three things make modern American patriotism difficult to sustain in practice: Firstly, most of our political leaders are interested in tapping the genuine patriotism of our people only in order to advance foreign and domestic policies that are aggressively imperialist.

Does a war deserve the support of patriots if it is being fought to aggrandize a narrow economic elite, or to fulfill the fantasies of a small cadre of megalomaniac idealists who believe that America should impose its will on the entire world? Admittedly, Pericles’s Athens was also engaged in political and cultural imperialism. However, I think that its citizens were genuinely threatened, which is why Pericles’s oration had an authenticity that the speeches of American politicians so often lack. Secondly, unlike Periclean Athens, the contemporary U.S. is a capitalist society, in which many people (perhaps most) identify ‘freedom’, first and foremost, with the freedom to consume. This leads to highly individualistic and hedonistic world view, not conducive to the self-sacrifices that Pericles extolled.

Most Americans will support an imperialist war without too many questions as long as it isn’t hugely expensive, doesn’t sacrifice their children and is fought primarily by aerial bombing, lower-class recruits and robotic drones. Once the war is perceived as costing too much in lives or money (e.g. Vietnam or Iraq), people begin to question whether the war is really worth it. Then public support very rapidly evaporates. Thirdly, the group that responds most favorably and persistently to calls for American patriotism are older lower-middle- or working-class white males, especially those who live in the Midwest and the southern part of the U.S. This is generally a declining class whose members once held good jobs in business or manufacturing, but who are now finding it difficult to replicate the lifestyle of their parents’ generation.

The ‘patriotism’ of this group is therefore tinged with feelings of resentment and nostalgia that the Tea Party and Republican Party have capitalized on very well. It is easy to convince this group that we are surrounded by enemies since they have a fear/hatred of foreigners, minorities and political leftists, whom they are taught by the media to blame for their own diminished lives.

Let’s not forget that Athenian citizen democracy rested on slavery. In the 20th century U.S., class inequality persisted, but much of the spontaneous patriotism of that era rested on the fact that the U.S. seemed to be moving in a genuinely meritocratic and egalitarian direction. Today, in the 21st century, the reverse is happening, and it is difficult to get people to believe that equality prevails, either in government, business or ordinary life. As a result, patriotism tends to give way to cynicism, especially among the young.

Zhang Jin is from the Institute of World History at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 623, July 21, 2014

Edited by Zhang Mengying

The Chinese link:

http://sscp.cssn.cn/xkpd/dh/201407/t20140721_1260958.html