Migrant-worker poets adapt to society through writing

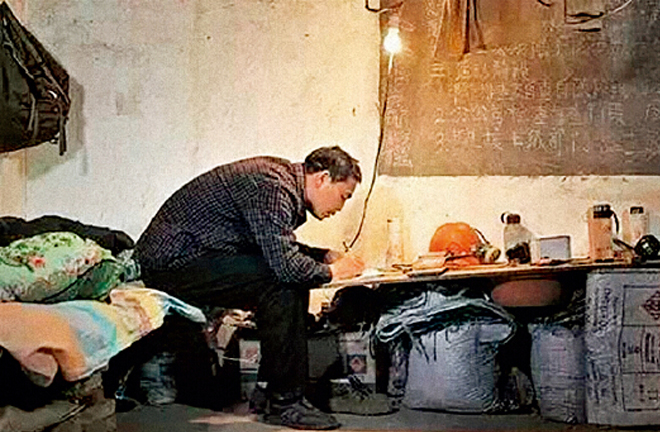

Chen Nianxi, a demolition worker turned poet who spent some 16 years of his life in and out of mining sites across China, earned the nickname “Blaster Poet” with his early poem “Demolition Mark” describing his life as a demolitionist. Photo: GLOBALPEOPLE.COM.CN

“Migrant-worker poets” have emerged in the industrial areas of the Pearl River Delta region, and the term generally refers to those who have left rural areas and engaged in low-level labor while writing poetry, two identities amalgamating into one. As a group of wandering marginalized people, migrant workers are “outsiders in the city” in the sociological sense, and they face emotional and identity challenges living far away from their familiar cultural settings and instead in urban environments full of strangers and risks.

In this sense, a probe into the writing activities of migrant workers not only expands the research on the group in the framework of social adaptation from the perspective of subject cognition and action, but also responds to classic issues in sociology. This article draws upon interviews and surveys of migrant-worker poets in the Pearl River Delta region from 2015 to 2017.

‘Growth adaptation’

Adaptive migrant-worker poets can comprehend the social background and structural factors that determine the living conditions of migrant workers to a certain extent, but this understanding is mainly a personal perspective. An expectation for income and opportunity, as well as a sense of mental and emotional oppression and a lack of belonging, are important dimensions of their experience and evaluation of the working life.

Writing poetry is a way for migrant workers to deal with their experience of the conflicting reality and adapt to the structural situation, revealing three types of coping mechanisms. The “compensatory type” seeks emotional support to overcome the lack of social ties and interactions. The “detached type” strives to move beyond the barriers of education and career to become more competitive individuals in the market. The “transcendental type” tries to escape from reality and somewhat achieve a status of “spiritual aristocracy.”

Like most migrant workers, migrant-worker poets work in the city mainly for economic purposes, but the improvement of income comes with a feeling of life imbalance, which is where writing activities come in to restore the equilibrium between economic interests and spiritual emotions.

In their poetry, migrant workers often juxtapose and integrate the contradictions they feel in their working life in an attempt to fully recognize the relationship between themselves and the social space. Through writing, they reflect on the pros and cons of working life and the corresponding emotional experience. In the twists and turns of life, migrant-worker poets strive to shape a complete and coherent self-identity and adjust the tension between themselves and the society.

Trapped in the structural situation, individuals seek coordination and balance while maintaining distance and tension with the society. Migrant-worker poets’ adaptation stems from the hope of upward mobility out of the status quo, rather than a recognition of the social status and living conditions as a migrant worker. In this study, the writing of migrant-worker poets reflects a kind of “ready for growth” adaptation, meaning that the individual adjusts himself or herself to adapt to the structural situation in order to survive and settle down in big cities, which is summarized as “growth adaptation.”

Such a concept can also apply to migrant-worker poets who end in tragedy. For example, the Foxconn worker poet Xu Lizhi took his own life at the age of 24. Xu pinned his hopes on modern cities but ended up disappointed by grueling working conditions and poor wages. According to interviews with Xu’s friends, the lack of upward mobility was an important cause of his desperation.

With the hope of change someday, Xu translated his pain and sorrow as an indispensable part of earning a better income, testing the body and mind, enriching life experience and achieving personal growth. As that hope dimmed, Xu found it hard to give positive meaning to the monotonous and tiring assembly line work and the suffering from chronic diseases. The various descriptions of suffering in his poems changed from “gritting one’s teeth to endure” and “vomiting” to “closing one’s eyes,” “leaving” and “going to the graveyard.” From the perspective of growth adaptation, Xu could not reconcile the tension between himself and reality due to the loss of prospects and hopes for the future, so life became an unbearable weight.

In general, migrant-worker poets cope with the structural pressure through internal adjustments using literary activities, which not only helps them harmonize the conflict between material and emotional desires, but also underlines their hope of moving upward in the established social structure. This growth adaptation is a practice of striving to maintain life integrity and development.

Compared with the progressive mode from economic adaptation to social adaptation, then to cultural and psychological adaptation, material gains and spiritual and emotional satisfaction are indeed divided and constitute a dichotomy, but they are not progressive relations with clear priorities, rather they co-exist and often clash with each other.

Self-identification

The investigation and research on migrant workers in the Pearl River Delta region shows that the group has been deprived of all-around family and community life, social interaction and emotional support, and leisure life and spiritual sustenance. In the face of frequent job changes, severe work pressure and atomized social contacts, personal spiritual crises tend to deepen.

Amid an imperfect, repetitive and lonely daily life, poetry offers an alternative, and meanwhile it aids the individuals’ adaptation to social changes by constructing a self-identity and easing the tension between oneself and reality.

This approach also helps to understand the social adaptation of migrant workers as a whole. For example, many migrant workers dream to start their own business and become their own boss someday, so they take work in precarious and unstable employment positions as a stepping stone, which constitutes a typical growth adaptation mindset.

Past research found that some migrant workers only consider their working life in the city as a way to gain economic benefits, and they still seek a sense of belonging from their rural community or people from their hometown, so as to construct their identity. In contrast, there are also migrant workers who actively accept the values of the city, learn job skills and local languages, and transform themselves according to the logic of market and development, to gain greater competitiveness.

As marginalized people in the modern society, migrant-worker poets show how individuals construct self-identities through writing. To put it simply, under the premise of upward mobility, they try to balance and coordinate multiple experiences, and incorporate negative feelings into a longer period of personal growth to identify positive significance. Literary activities help individuals achieve new self-integration in the tension with structural situations.

In traditional Chinese Confucianism, self-identification contains a rich connotation within the denotation of morality, but since the 1980s, individual dreams and successes have been highlighted, giving rise to the description of individualism in migrant-worker poetry consistent with the individual image shaped by commercialism and consumerism.

However, in their struggle toward becoming urban middle class, migrant-worker poets also present a different aspect of contemporary Chinese social individualism in their identity construction—on the basis of advocating free will and self-responsibility, they seek a balance between “material” and “heart” and value comprehensive self-development. The growth adaptation reflected in literary activities combines the characteristics of instrumental rationality and value rationality, utilitarian individualism and expressive individualism, and constructs a balanced and upward self in the established social structure.

At the same time, in literary writing and poetic texts, better material life, higher social status and more fulfilling family life and social interaction are seen as sources of emotional satisfaction and self-worth. Therefore, this goal of self-development is not restricted to class mobility, but can be regarded as life improvement.

Adaptive migrant-worker poets stress their own adjustment and change, rather than look for the structural causes of their own circumstances. However, their literary writing not only serves instrumental rationality, but also reflects material desires. By shaping a self-form that attaches importance to the inner spiritual depths and the emotional dimension, their poetry, to some extent, constitutes resistance to the discourse of industrial civilization, commodity logic expansion and neoliberal development.

Liu Chang is from the School of Sociology at Wuhan University.

edited by YANG XUE