Applying Marxist urban politics to solving city problems

ce.cn

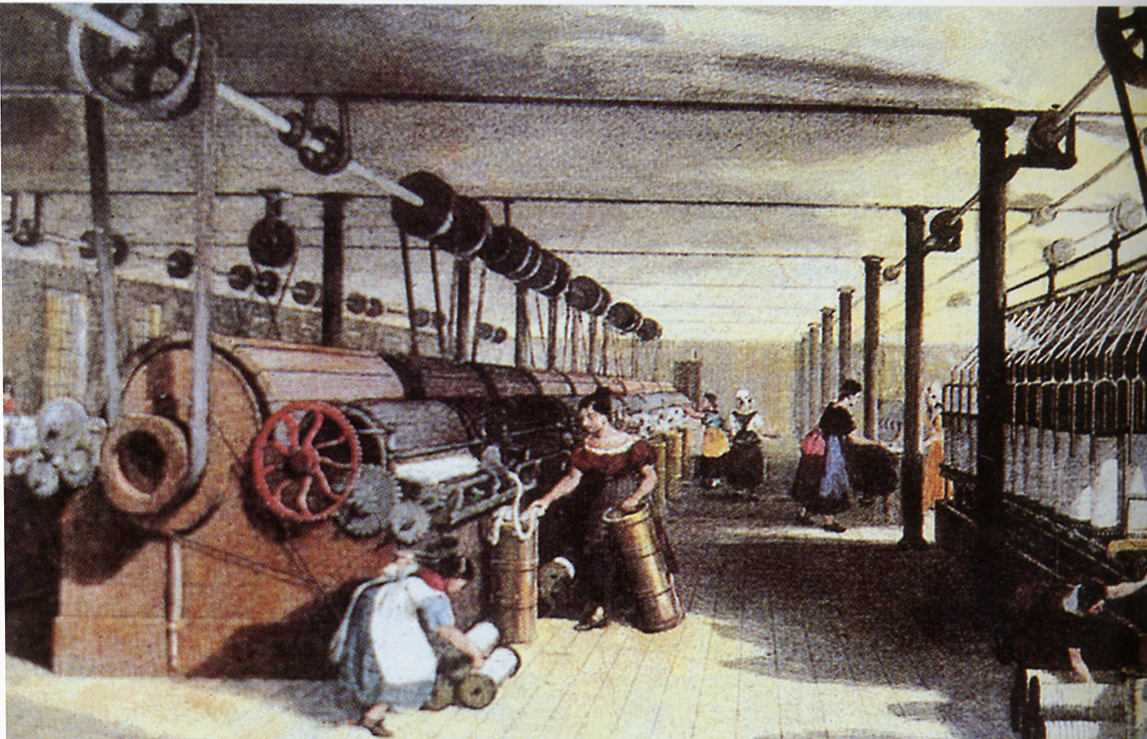

Employers were working in a cotton mill in Britain after the Industrial Revolution.

The capitalist city, a product of the Industrial Revolution, was consistently a focus in the works of Marx and Engels. They frequently discussed urban problems in classics such as A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, The Condition of the Working Class in England and The German Ideology. They integrated the notion of urban space into a broader vision of historical materialism, leaving a legacy of theories on urban politics. As the former Soviet Union urbanologist Demidenko said, classical writers of Marxism-Leninism establish a comprehensive theory on city and country with an eye toward the restrictions of history on urban development, laying a theoretical foundation for scientific urbanization.

Capitalist city

One of the remarkable features of Marxist urban politics is the application of the analytical paradigm of political economy. From a Marxist perspective, the industrial city is not just a place that serves as a gigantic container for capitalist production. The space it provides is an important link in the process of capital accumulation.

The primary function of the capitalist city is to meet the demands of capital accumulation and expansion. In terms of the factors of production, the flourishing of the Industrial Revolution not only facilitated the development of industry, transportation, finance and commerce but also sparked an influx of the most important factor—human capital to urban areas from rural areas.

As a result, the surplus labor population forms an industrial reserve army in the city, providing human resources which, available for exploitation, serve as a lever for the accumulation of capital. In addition, the revolution in science advances technological progress, making the city a testing ground for the transformation of new technologies into productive forces.

Engels theorized the reasons for urban growth and geographical concentration as well as the economic benefits brought by the cluster of economies and people.

In The Condition of the Working Class in England, he wrote in figurative language, "A town, such as London, is a strange thing. This colossal centralization, this heaping together of two and a half million human beings at one point, has multiplied the power of this two and a half million a hundredfold, raising London to the commercial capital of the world, creating the giant docks and assembling the thousand vessels that continually cover the Thames." Engels affirmed the productive forces and capital accumulation generated by large-scale agglomeration. According to Marx and Engels, it is the function of agglomeration and radiation rather than the geographic space itself that makes the industrial city of modern capitalism attractive. In essence, the city is not just the physical form of a certain geographic space but embodies a cohesive force and the resulting space advantage.

Urban-rural antithesis

Of all the urban problems they dealt with, Marx and Engels elaborated the most on the distinction between capitalist town and country. In The Communist Manifesto, terms such as "the distinction between town and country", "the differences between town and country" and "the rule of the towns" were used to describe the relationship between urban and rural areas. Marx and Engels spoke highly of the measures advised by other socialists (champions of Critical-Utopian Socialism), including the abolition of all distinctions between town and country.

They delved deeply into the evolutionary trend of urban-rural relations, mapping out a route of "unification—separation—distinction—integration" and putting forward several propositions to abolish the distinction between town and country.

From the perspective of Marx and Engels, urban and rural areas were unified in the early human society, which is the origin of the relationship between town and country, and they noted that it was only after the capitalist city came into being that antagonistic relations arose. The antagonism between town and country, a product of the division of labor and the development of productivity, makes it possible for the capitalist mode of production, featuring mechanical industry, to replace slavery and feudalism and for advanced industrial civilization, featuring industrialization and urbanization, to replace the backward agricultural civilization.

Marx observed that in the process of the antagonism, the prosperity of towns relieved agriculture of underdevelopment in the Middle Ages. The economic history of society is a history of such antagonism, he added. He also discovered with acuteness that though such antithesis creates conditions necessary for the development of civilized society, it meanwhile poses an impediment to the further development of human society.

In the process of the urban-rural antithesis, the city plays a dominant role with the country in a subordinate position. Labor and capital, driven by the development of industrial production, rapidly concentrate in cities, causing isolation, decline and fragmentation in the country, which is relegated to a position of subjugation. It has, as the two thinkers wrote in The Communist Manifesto, made the country dependent on the towns; nations of peasants on nations of bourgeois.

The division mirrors the fracture of social space in capitalist society. The urban-rural dual structure represents a significant perspective from which Marx and Engels criticized capitalist towns. They thought that the urban-rural antithesis classifies people into two categories: "urban animals” and “rural animals". The former is enslaved to the specialized skills required by each industry, while the latter becomes a victim to the isolation and ignorance of themselves. Such abnormal and unbalanced development, Engels maintains, is more obvious in the working class. As a consequence, workers swarm into towns, where they develop a class consciousness, making it inevitable for class struggle to take place in towns.

Town as a production center

The agglomeration of population and other social elements (politics, economy, cultural institutions and activities), the essential feature of towns, provides important conditions necessary for industrial production. The inflow of capital to towns intensifies the collisions between the two great classes: bourgeoisie and proletariat. The town becomes a center for the means of production, so large numbers of peasants flock to towns and thus the proletariat emerges.

Marx once made a comparison: "that union, which the burghers of the Middle Ages, with their miserable highways, required centuries to attain, the modern proletarian, thanks to railways, can achieve in a few years." In fact, the formation of this union benefits from the town-based industrial production and as Marx put it, "it’s modern industry that creates the working class".

Marx attempted to stage a "spatial revolution" by virtue of the immensely facilitated means of communication that are created by modern industry. He and Engels constantly stressed the importance of "united action" in proletarian revolution, insisting that the working class should be united on a wider range. The alliance is worldwide, as he pointed out, "The working men have no country."

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx championed the conquest of political power and the establishment of dictatorship by proletariat and maintained that towns, without doubt, remain the battleground for the struggle between the two great classes. Large towns in particular are home to the labor movement, as Marx observed, it’s in towns where workers began to think about their situation and campaign for better conditions; where antagonism between proletariat and bourgeoisie appeared; where the workers’ organization was formed, Chartism took place and socialism germinated.

The development of towns determines how Marx and Engels constructed revolutionary theories. The core of their urban theories is that the reason for any phenomenon in modern cities should be attributed to the capitalist mode of production, whose abolition is the prerequisite to thoroughly addressing any urban problem. In a word, Marxists believe, whether for revolution or reform, that towns are the arena for struggle.

These classical theories first postulated by Marx and Engels have exerted a great influence on posterity. In the 1960s, neo-Marxist urban theorists represented by Lefebvre, Castells and Harvey carried on the mission of Marx and Engels. Thus, Marxist urban politics, having taken on the form of neo-Marxism, continue to provide guidance and inject vitality in the practice of production.

Cao Haijun and Sun Yuncheng are from the Politics and Public Administration College at Tianjin Normal University.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 607, June 13, 2014.

The Chinese link:

http://www.csstoday.net/xuekepindao/zhengzhixue/90025.html

Translated by Ren Jingyun