A lingering taste of Chinese calligraphy

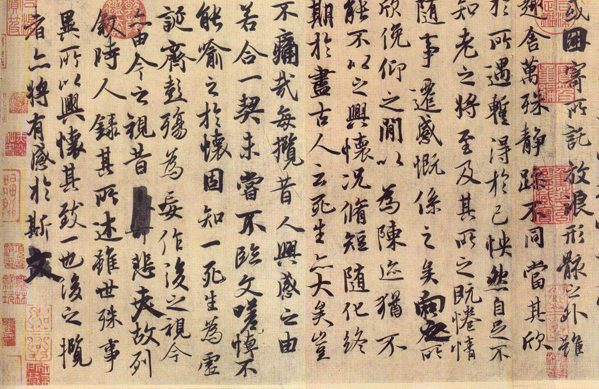

The “Lanting Xu” (“Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion”) by Wang Xizhi (303–361). The work is celebrated as the high point of the running style in the history of Chinese calligraphy. Photo: FILE

Works of calligraphy are often seen as an analogy for the works of nature. As calligrapher Wei Heng (?–291) described it, “Strong and vigorously the brush goes, like a dragon rising from a deep river. High above it falls, like raindrops falling from the sky.”

Calligraphy is also often linked to one’s own senses of taste, smell, hearing and touch. “Taste,” in particular, can be used to describe all kinds of philosophies, ideas or styles in calligraphy. After the Six Dynasties period (222–589), articles and calligraphic works had begun to be judged based on their various “tastes.”

A calligraphic work is not only the result of its creator’s technical skill and talent, but also a carrier of Chinese wisdom, for it is rooted root in Chinese tradition. Its philosophical beauty is beyond words and can only be felt; by echoing or dodging one another, the dots and lines embody the dialectic; by artfully arranging the density among characters, or the configuration, the calligrapher breaks the uniformity and creates a new sense of harmony in his work; and by controlling the beginning and the end of a stroke, the writer gives the work a touch of restrained beauty.

Form and spirit

A calligraphic masterpiece must combine both the xing (form, outer shell) and the zhi (spirit). In his book Shuduan (Judgement on calligraphers), Tang Dynasty calligrapher Zhang Huaiguan thus criticized the works of Wang Sengqian (426–485; also known as “Wang Jr,” the fourth generation descendent of the “Sage of calligraphy”, Wang Xizhi): “Wang Jr.’s works are like the clear water in a mountain stream, or a hill covered in snow. Solemn and peaceful, they taste plain.”

In another critique, Wenzi Lun (On Writing), Zhang also mentioned “taste” as he criticized the works produced with one’s eyes but not with one’s heart: “Some works might be highly functional, skillful and well-received, but they are not original, nor do they convey any message of Nature. These works are nothing but dross. One can easily know how they taste. Any piece of work that is not created by heart is doomed to lack spirit.”

Without “spirit,” a work of calligraphy has no inner beauty, which makes its pretty form meaningless. However skillful a calligrapher is, without enough emotional depth and cultural instinct, one can only come up with a shallow piece of work. In a masterpiece, the two elements are not simply added up, but work as an organic whole. The work is the natural outburst of a calligrapher’s emotions and ideas. Although its form can be imitated by others, the spirit within it can never be the same. However, the spirit doesn’t come easily. After all, calligraphy is not painting.

Force

Qi shi (force) is the momentum, or dynamic tendency brought about by a calligrapher’s fingers, wrist and arm. The calligrapher can only work in concert with the directional force while wielding the brush. Song scholar Jiang Kui (1155–1221) wrote in Xu shu pu (Sequel to the “Treatise on Calligraphy”): “With horizontal, slanting, curved, and straight lines, hooks, circular lines, and spirals, shi is the most important element” (trans. Chang Ch’ung-ho).

In Bodeng Xu (Discussion on Adjusting the Stirrups), Tang scholar Lin Yun cited a sentence from Hanlin Jinjing (Forbidden Classic of the Hanlin Academy): “Calligrapher Han Fangming once taught me his technique, namely the ‘bodeng technique.’ Today I’m passing it on to you, and do not share it with others lightly. The laws of wielding the brush include: pressing, dragging, twiddling and quick pulling. These are all the techniques you need to know, but you should understand their meanings as well as their tastes!” By “tastes”, the speaker meant shi.

Shi is a masculine force, since it is full of vigor and power. Shi refers not only to the calligraphy that is already on the paper, but also the potential or tendency of the brush. Shi has a lot to do with how strongly one wields the brush. For instance, when calligraphers talk about how the second stroke of力(li, strength) should be written like a crossbow that is tightly pulled back, they are stressing the use of Shi, or the strength of calligraphy.

State of mind

A masterpiece can only be created when the calligrapher puts his/her real emotions into the work. As Zhao Gou (1107–87, Emperor Gaozong of the Song Dynasty) wrote in his Hanmo Zhi (Treatise on Brush and Ink): “Studying Wang Xizhi’s work is like eating olives. Not so sweet at first, its flavor intensifies as it lingers on.”

In Shufa Yayan (Talking about the Calligraphy), calligrapher Xiang Mu (1605–1691) of the Qing Dynasty stressed impartiality when appreciating calligraphy: “With his moral disposition and righteousness, Confucius possessed the temperament to be impartial. If one is able to fully ‘taste’ Confucius’ principles and apply them to the way he/she views others and learns calligraphy, his/her skills of writing and appreciation will both improve.”

The “tastes” mentioned above concern the emotions of calligraphers, which can be triggered by incidents and later inspire them to understand their lives and the nature of being. However, a calligrapher’s sentiment tends to go well beyond facial expressions, unfolding itself onto the paper as vivid dancing strokes.

Writing is an outlet for a calligrapher’s feelings. It is through writing that the calligraphers organize their thoughts or distract their minds. This kind of inner activity might help them produce works that can generate different emotional responses from different viewers.

Fusion

“I adore the works of Han (206 BCE–220 BC) calligraphers, since their style is between seal script and clerical script—grand, vigorous and classic. But after the era of Emperor Huan of Han (132–168) and Emperor Ling of Han (156–189), there was a tendency to renovate the traditional style, losing the original flavor,” wrote Philosopher and politician Kang Youwei (1858–1927) in Guang Yi Zhou Shuang Ji.

When Kang mentioned “flavor” he was emphasizing the need for calligraphy to be a fusion of multiple elements. Calligraphy continues to enrich itself by drawing from various sources. Take the calligraphy works created during the Wei Dynasty (220–266) and Jin Dynasty (266–420) for example, they are expressive and artistic because different styles of calligraphy had matured and interacted at the time.

Apart from styles, the importance of fusion is also shown in the process of creation. Calligraphers must infuse their personalities and styles into their work, which should also be the mixture of both force and flexibility, sturdy structure and a full figure. In addition, to avoid weakness, critics specially stressed that “masculinity” and “feminity” should be complementary.

Way of nature

We can even “taste” how much a calligrapher understands the Tao, a concept brought about by ancient philosopher Laozi, meaning “the natural order of the universe.”

Zhang Huaiguan wrote in Pingshu Yaoshi Lun: “Great ingenuity appears to be stupidity, and a man of great wisdom appears to be ignorant. Those who merely skim the great works fall easily into false wisdom, whilst those that painstakingly study the ‘flavors’ of the pieces tend to be overwhelmed by the spirits and messages staring right back at them.”

By “studying the flavors,” Zhang was talking about how essential it is to contemplate and seek the Tao. The ideas of Taoism are at the center of calligraphy appreciation. Only with a clear state of mind can the calligraphers“taste” the endless cycle of life and strip themselves of the restrictions outside so that they can freely transform their feelings and ideas into the rising wind and tumbling clouds in the form of dots and strokes.

The article was edited and translated from Chinese Art News. Ji Shaoyu is a member of China Literature and Art Critics Association.

edited by WENG RONG