Clan migration drove transformation of early states

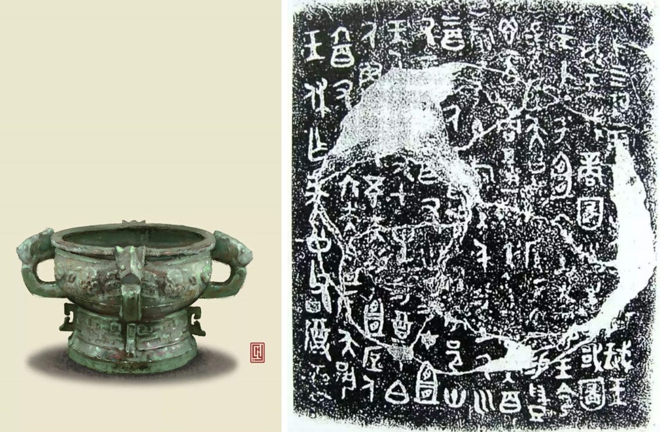

The picture shows a gui, a round-mouthed food vessel with four loop handles, made by Ce the Marquis of Yi to thank the King of Zhou for the many rewards he bestowed on Yi, and the inscriptions on the vessel, which have been valuable to the study of the enfeoffment system in the Western Zhou Dynasty. Photo: FILE

What we often call early states actually are immature states. In the case of China, early states refer generally to the Xia (c. 2070–1600 BCE), Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) and Western Zhou (1046–771 BCE) dynasties. Although public power had emerged as royalty at the time, territorial relations between social organizations were too immature to replace the dominant kinship relations. The disintegration of the kinship system was crucial before the early states could transform into mature territorial states.

Controversy

Opinions vary in academia concerning the transformation. Wang Yuzhe, a renowned expert of pre-Qin history, noted that blood ties of clans, or gentes in Roman terms, gradually loosened in the late Shang Dynasty due to conflict of economic interests within classes and clans alongside the development of commerce. Some families and clans began to live together with groups of non-blood relatives, undermining the regional integrity of clans and prompting the substitution of territorial relations for kinship.

Lin Yun, a professor from the School of Archaeology at Jilin University and former vice president of the university, argued that most cities developed into pure agricultural settlements prior to the Xia Dynasty due to the division of social functions. The non-agricultural population that emerged from the division, such as priests and warriors, started to gather in large central cities or states, turning states into territorial organizations comprising people of different bloodlines.

Shen Changyun, a famous professor of history at Hebei Normal University, said that blood-based organizations in Chinese society didn’t dissolve until the Spring, Autumn and Warring States Period (770–221 BCE), which featured dramatic changes in productive forces and production relations.

These scholars interpreted the breakup of the kinship system in ancient social organizations from the perspectives of class and economics. In fact, China entered the civilized age when the commodity economy was quite backward. The development of productive forces didn’t so much break the boundaries formed by bloodlines in clan society as accelerate them.

Inscriptions on ancient bronze objects and documents of the Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn period suggest that social relations based on blood ties remained universal then. Therefore, the views that regional relations had replaced blood ties in the Shang Dynasty are not tenable.

In the Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn period, the principal social contradiction was one between ruling clans and ruled groups, rather than the antagonism between different classes. The author of this article maintains that the mass mixing-up of different clans was the real force driving the disintegration of kinship in social organizations. And the most important cause of this was the long-term policy of clan migration implemented by the Shang and Zhou dynasties.

In the stage of the early state, Chinese rulers dealt with subjugated clans in three ways: forcing all members of the clans to move to other places; reducing them to slaves to be distributed to ministers; or allowing them to remain independent as vassals nominally. The former two methods naturally would lead to clan migration and the third didn’t necessarily prevent it.

Scale of intermixing

The forced migration of subjugated clans was a mature policy in the Shang Dynasty. In order to tighten the control over its vast territory, the kings of Shang carried out a two-part strategy.

First, they would arrange dependent clans or members of the same clan to build military strongholds in places far away from the ruling center, so as to control and deter surrounding regions, alliances of city states, and tribes. They even asked the populace to reclaim land in subject city states, yet the reclaimed land would be owned by the Shang kings. Second, they would compel some of the subjugated clans to move to and settle in the capital for the purpose of closer surveillance.

According to famed historian Song Zhenhao, who is also a research fellow and Member of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), the population grew sixfold in the capital Yin, modern-day Anyang in Henan Province, during the reign of King Wuding. This period also marked a peak of outward expeditions by the Shang Dynasty. The unusual population growth in the late Shang Dynasty was obviously a result of forced migration.

Archaeological data shows that numerous bronze objects engraved with clan emblems were unearthed from tombs in Yinxu, or the ruins of Yin. Each clan emblem represented a clan based on blood ties, and many clans moved to the capital from other places. Wang Zhenzhong, a research fellow, CASS Member and former deputy director of the Institute of History at CASS, said that clans of different bloodlines from various places intermingled in the capital Yin. They lived and were buried according to their clan.

After overthrowing the last Shang ruler, the Zhou government improved its two-part ruling strategy. The enfeoffment system practiced in the early Zhou Dynasty was, in essence, the kings of Zhou ordering members of the Zhou clan or dependent clans to lead captives of Shang to build military strongholds in areas far away from the ruling center, while relocating some new subject clans to the capital for closer surveillance. In recent years, many scholars have sorted materials such as inscriptions and tombs regarding clans in the Western Zhou Dynasty and found that many people from Yin lived in the metropolitan area, the same as other clans from the eastern part of China.

Inscriptions on Western Zhou bronze objects show that nobles of different clans shared the same surname due to the large-scale intermingling of clans. According to inscriptions on a gui, a round-mouthed food vessel with four loop handles, the King of Zhou awarded 17 surnames, seven countesses and hundreds of subordinates to people of the Zhou clan in Yi. This gui was made by Ce the Marquis of Yi to thank the King of Zhou for his gifts. It indicates that many clans inhabited the place Yi.

Transformation

In his 1884 monograph Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Friedrich Engels said that the necessary condition for the existence of the gentile constitution was that the members of a gens or at least of a tribe were settled together in the same territory and were its sole inhabitants. The formation of a state necessitates the breakdown of blood ties among clans to realize the division of citizens by region.

Take Ancient Greece as an example. Before the reform ascribed to Theseus in Athens, “through the sale and purchase of land, and the progressive division of labor between agriculture and handicraft, trade, and shipping, it was inevitable that the members of the different gentes, phratries, and tribes very soon became intermixed,” Engels wrote.

As a result, the organs of the gentile constitution, which were supposed to handle internal affairs of their own gens, phratry and tribe, were gradually incapable of coping with the increasingly complicated social affairs.

Through the reform, a central authority was set up in Athens, “that is, part of the affairs hitherto administered by the tribes independently were declared common affairs and entrusted to the common council sitting in Athens.” Public power thus overrode the entire society.

After the revolution of Cleisthenes in 509 BCE, four old tribes founded on gentes and phratries were ignored. “The whole of Attica was divided into one hundred communal districts, called ‘demes,’ each of which was self-governing. The citizens resident in each deme (demotes) elected their president (demarch) and treasurer, as well as thirty judges with jurisdictions in minor disputes.”

The completely new institution divided the citizens merely according to their place of residence, not membership of a kinship group. “Not the people, but the territory was now divided: the inhabitants became a mere political appendage of the territory.”

The emergence of public power and the division of citizens by territory rather than kinship marked the transformation of Athens into a mature territorial state. The precondition for the situation was a process of different gentes, phratries and tribes intermixing, so as to remove the barriers among them posed by kinship.

Different from Athenian reforms, China went through a very long period before blood ties were replaced by territorial relations. The policy of forced migration implemented by the Shang and Zhou royalty was critical to the transformation.

Shen held that different clans and tribes never intermixed prior to the Western Zhou Dynasty. It was the dynasty’s enfeoffment system that provided opportunities and conditions for the mixing-up of clans and tribes in ancient China. The above analysis indicates that such politically led policies had started before the Zhou Era. During the Western Zhou period, the scale of migration and intermixing was expanded to an unprecedented degree. The exchange and intermarriage between different clans developed as never before, as blood boundaries became actually blurred.

The demise of the Western Zhou Dynasty disrupted the historical process of its transformation into a territorial state. However, the factors didn’t change. The historical tasks that the Zhou Dynasty didn’t finish were taken over by vassal states, and social transformation that was not realized through reforms came true in the form of war.

During the Spring and Autumn Period when many vassal states fought and competed for supremacy and aristocratic families merged for the sake of power, clans based on blood ties completely disintegrated, and the populace passively broke away from clan control.

After reforms in the Warring States Period, the citizens divorced from clans were subject to the direct administration of centralized states. Early states of the Xia, Shang and Western Zhou style thus completed the transformation into mature territorial states.

Huang Minglei is from the Institute for Western Frontier Region of China at Shaanxi Normal University.

edited by CHEN MIRONG