Chinese ethnography explores new approaches

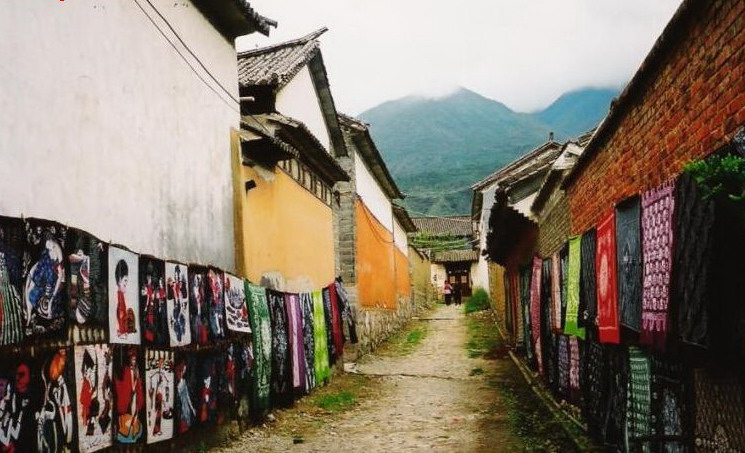

A village of Bai people in Zhoucheng, Dali city, Yunnan Province

Ethnography is the coming of age rite for anthropologists. From the discipline’s conception, anthropologists have avidly explored the ethnographic paradigm. Throughout its development, the juxtapositions between science and the arts, subjectivity and objectivity, and proof versus explanation have progressed hand in hand.

Professor Gao Bingzhong from the Department of Sociology at Peking University divides ethnography into three periods. During the first period, he says, ethnography was characterized by spontaneity, randomness and amateurism, while in the second period it took on a certain scientific rigor and developed norms. Works like Bronisław Kasper Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An account of native enterprise and adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea stand as a magnum opus of this period, Gao contended. He sees the third period as a time of reflection on the “scientificity” of anthropology, with works like Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography representing the general sentiment and focus.

Influenced by postmodernism, American anthropologists turned toward the study of interpretation in the 1970s. They questioned the objectivity of scientific methods praised by writers of classical ethnography, with some insisting that transcendent objectivity in anthropology is a myth. Writing Culture was incubated under this influence.

Many commentaries and other texts reflecting on postmodern anthropology specifically pointed out that ethnography contains elements of both poetics and political science. Because it is a product of the imagination, ethnography is bound to resemble literature in some respects and thus can be considered a form of poetics, these authors argue. They also liken ethnography to political science because the textual practice is limited and affected by the system of authority, and the modes of resistance to that system. Ethnography is determined by institutions, politics and history.

30 years later, In January 2013, the French journal l’Humanité mentioned “subjectivity” and “human subjectivity” once again. Does this indicate that the postmodern criticism of anthropological ethnography never subsided?

Some scholars remain wary of what the unhealthy influences of postmodernism. They believe that Chinese academia still has plenty to glean from modern Western ethnography.

Skepticism toward the arguments advanced in Writing Culture, as a representative postmodern take on the field, has forced anthropologists to rethink their discipline, said Gao Bingzhong. “Introducing these two dimensions—poetics and politics—to China complemented our scientific ethnography with textual richness.”

“More and more scholars started attempting to innovate in their works. Collaborative ethnography and multi-sited ethnography are among some of the more influential explorations coming out of this,” said Gao.

In recent years, Chinese ethnography scholars have been pioneering different ways of adapting forms to better suit China’s national conditions. Innovation of research methods based on Chinese society, culture and people has been continuous. “Ethnography of the common people” by Luo Hongguang, a research fellow of CASS’s Institute of Sociology, “Overseas ethnography” by Gao Bingzhong and “Ethnography of places and clues” by Zhao Xudong, a professor from the Institute of Anthropology at Renmin University of China, exemplify these trends.

Zhu Bingxiang suggested that experimental ethnography may be able to pull itself out its current lull by approaching writing from a new paradigm. What Zhu calls “subject ethnography” tries to address unresolved issues from postmodern ethnography, including the paradox of epistemology, the crisis of representation and research goals.

Zhu Bingxiang elaborated: “I analogize the paradox of epistemology to two mirrors placed opposite each other. The image in the mirrors becomes incredibly complex as different subjects map to different objects.”

For the crisis of representation, Zhu has proposed the concept of “bare presentation”, where the ethnographer directly shows the people and culture’s forms of existence. “For instance, in conducting field work, we should let local people talk about the issues that interest them and describe the local culture and their pasts, their thoughts, their feelings and their understandings. We should show their ‘existence’ by letting their personal experience flow without boundaries. ‘The secondary subject’ is only a listener and recorder instead of a guide or questioner.” Zhu plans to write five volumes of “subject ethnography” under the theme of “The Antipodeans” based on field work he conducted in villages of the Bai people in Zhoucheng, Dali city, Yunnan Province.

Peng Zhaorong, a professor from the Department of Anthropology and Ethnology at Xiamen University, believes that the primary mission for Chinese ethnography is to return to embracing the intellectual subjects of Chinese culture, which is its innate disposition. “We should regard the grammar of the paradigms used in Chinese ethnography as a base. This grammar should conform to the ‘grammar’ of Chinese culture. Only if we achieve this will we have created a genuine, localized ethnography.”

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 587, April 23, 2014

Translated by Zhang Mengying

Revised by Charles Horne

The Chinese link:

http://www.csstoday.net/xueshuzixun/guoneixinwen/89192.html