Dunhuang studies renowned globally for unique history

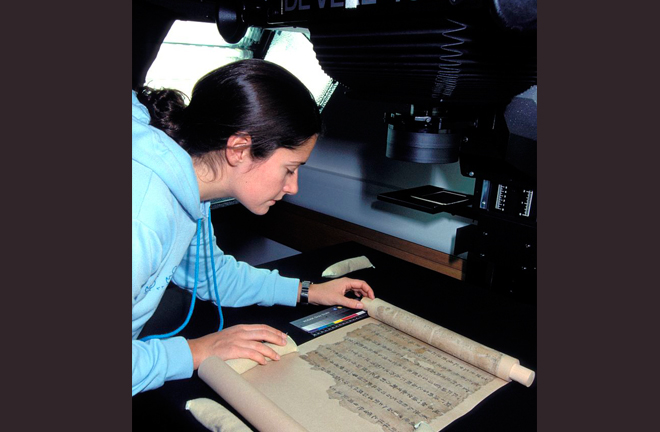

A scholar digitizes a Dunhuang manuscript. Photo: WIKIPEDIA

In the global academic community, Dunhuang studies is distinguished among research areas that are named after places. Today, Dunhuang is simply a county-level city in northwestern China. It is incomparable to domestic metropolises such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, not to mention international cities such as London, Paris and Tokyo. However, there is no London studies, Paris studies, Beijing studies or Guangzhou studies in the world. Why is Dunhuang so special as to entitle an area of research all by itself and to draw attention from all over the world?

Unique status

Dunhuang attracts the attention of the world for its uniqueness. Without the Dunhuang Grottoes, few international organizations, or even China’s general public, would know the city. And without Dunhuang studies, few global scholars would know it so deeply.

The geographic location of Dunhuang determines its special historical status. During the Han and Tang dynasties (206 BCE–907), it was the “throat” of the Silk Road, and the Silk Road was the major route for China’s foreign contact for a long period.

Over the thousand years during the Han-Tang era, northern China was the economic center of the country, while the political hub lay in the northwest. The Silk Road in the west was the thoroughfare for external exchanges.

During the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (141–87 BCE), around the time when the military general Huo Qubing defeated the Xiongnu nomadic confederation and the diplomat Zhang Qian was dispatched on missions to the Western Regions, the Prefecture-County system was replicated in modern-day Hexi Corridor in Gansu Province after the inland. It established Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan and Dunhuang prefectures, which were dubbed the “Four Prefectures of Hexi.”

At the time, Dunhuang Prefecture ruled six counties, namely Dunhuang, Ming’an, Xiaogu, Yuanquan, Guangzhi and Longle, including today’s Dunhuang City, Guazhou County, Yumen City, the Kazak Autonomous County of Aksay and part of the Subei Mongolian Autonomous County.

There were many routes from the capital Chang’an, present-day Xi’an in Shaanxi Province, to Dunhuang. After entering the Western Regions from Dunhuang, there were the northern, central and southern lines, all of which Dunhuang served as a mouth. Therefore it was a nexus for exchanges between the East and the West.

Because Dunhuang was the throat of the Silk Road and the hub for East-West communication, the Han Empire set up the Yumen Pass and Yangguan Pass to the west of the critical prefecture, exercising control over the East-West travel of merchants.

Via Dunhuang on the Silk Road, exotic species and cultures were introduced to China, including products like grapes, alfalfa, walnuts, flax, broad beans, cucumbers and pomegranates; religions such as Zoroastrianism, Nestorianism and Manicheism; and arts such as Western music, painting and sculpture.

In the meantime, Chinese silk and silk fabrics, steel and smelting techniques, as well as exquisite handicrafts like lacquerware, bronze mirrors and porcelain were brought via Dunhuang to the north and south of the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang and Central Asia, and they spread to Europe via Central Asia. Later the papermaking, printing and gunpowder of the Four Great Inventions of China were also exported to the West via this route.

Its unique status in the Silk Road and East-West cultural exchanges has endowed Dunhuang with conditions worthy of detailed study.

Incomparable academic value

The distinctive status of Dunhuang determined its crucial role in ancient China, yet the emergence of Dunhuang studies and its far-reaching influence should be attributed to the discovery of invaluable manuscripts.

In 1900, Taoist priest and abbot Wang Yuanlu, who was a self-appointed caretaker of the Dunhuang Grottoes, discovered the “Library Cave,” or No. 17 Cave, which housed more than 50,000 volumes of Chinese medieval manuscripts of various fields. The documents were mostly Buddhist, alongside Taoist, Nestorian and Manichean records. Apart from religious manuscripts, there were also materials spanning politics, economics, military, geography, linguistics, literature, music, dancing, astronomy, mathematics and medicine, among other fields.

The Dunhuang manuscripts have incomparable academic value because in the Chinese historiographical tradition, it was later generations that wrote the history of the previous dynasty, rather than contemporaries compiling the history of the current dynasty.

In this tradition, historians usually extracted, analyzed and explained official records from the previous dynasty based on the ruler’s order and their own morals and knowledge. As scholars write papers or monographs today, they might collect lots of historical materials, but only a few, perhaps merely a tiny part of the collected materials, will be applied to their works.

After a long course, historical books like the Twenty-Four Histories and Comprehensive Mirrorr to Aid in Government have been passed down, but not original archives. Moreover, most of the historical documents were outlines due to historians’ varying knowledge, talent and morals, in addition to their positions and political preferences, the ruler’s ideology, and restrictions on genre, format and length.

For example, the equal-field system, or land equalization system, a system of land ownership and distribution practiced from the Northern Wei to mid-Tang dynasties (485–780), was briefly outlined in such books as The Old Book of Tang, The New Book of Tang and Comprehensive Mirrorr to Aid in Government. The lack of specific content raised doubts among later historians whether the system was ever implemented or not.

Manuscripts discovered in Dunhuang, which were original documents neither processed nor changed by later generations, contained details of the equal-field system, such as land granting, return and default. Regarding land return, detailed stipulations were provided saying that land should be returned when one grew old, got married or died.

By studying and interpreting these documents, we have learnt that the system was indeed carried out.

The Dunhuang manuscripts are so wide-ranging that they are called an “Academic Ocean” or “Encyclopedia of Medieval China.” Though found in Dunhuang, they are by no means merely local documents about the city. They are national.

Not only were they transcribed in Dunhuang, but many were brought to Dunhuang after being transcribed in Chang’an, Luoyang, and even southern China. The manuscripts reflect not only local history and the culture of Dunhuang but also national history and culture. Besides Chinese manuscripts, there are Sanskrit, Sogdian, Syrian and Hebrew documents mirroring the histories and cultures of other countries. They are excellent materials for understanding and researching world history and cultures.

Colorful cave arts

Apart from its special geographic location and encyclopedic manuscripts, the grottoes have also contributed to Dunhuang’s prominent status in global academia. In this regard, it is unrivaled by regional studies such as Tangut studies, Huizhou studies, and Turpan studies.

The Mogao Caves, part of the Dunhuang Grottoes, are situated on the eastern slope of the Mingsha Mountain 25 kilometers southeast the center of Dunhuang. From the 4th to 14th centuries, people carved caves and built Buddha statues here continuously, bringing into being a group of grottoes spanning about 1,700 meters from south to north.

Now the Mogao Caves are generally divided into the southern and northern sections and composed of 735 caves. The 487 caves at the southern section were places of pilgrimage and worship, with more than 2,400 painted statues, more than 45,000 square meters of murals, and five wood-structure eaves from the Tang and Song dynasties (907–1279). The 248 caves in the north were living quarters, meditation chambers, and burial sites for monks. Inside were facilities for practice and living, such as earthen beds, cooking pits, flues, niches and lamp stands, and most of the caves had no painted statues or murals.

It is not an accident that such magnificent cave arts were created in Dunhuang, a border prefecture in the west of China then. They are the result of a combination of various factors. The culture of the Central Plains started to accumulate in Dunhuang in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220), particularly in the Wei and Jin dynasties (220–420) when cultural exchanges between China and the West prospered. As the throat of the Silk Road, Dunhuang was the first to be exposed to the cultures and arts of Central Asia, South Asia, West Asia and Europe, so that Buddhist arts and cultures took root here.

Dunhuang arts are Buddhist arts that originated from India and were introduced to China via Central Asia. Thus there are necessarily many traces of Indian and Central Asian arts in the Dunhuang Grottoes. For example, the Mogao Caves are an integration of architecture, mural and sculpture arts. Regarding the murals alone, they portray ethnic groups and all walks of life in China from multiple perspectives, such as productive labor, customs and rites; emperors, generals and ministers; noble women; traveling merchants; tributary envoys received at court; ethnic relations; music and dance; garments and accessories; astronomy and geography; and health care. That is why the French called them a library on a wall.

The Dunhuang Grottoes crystalize the Buddhist arts. In addition to Buddhism, there are many other themes. The glassware discovered on a mural exemplifies the artistic style of Sassanian Persia, based on which one could carry out a study on the making of glassware in West Asia.

Liu Jinbao is vice chairman of the Tang Dynasty Institute of China.

edited by CHEN MIRONG