Early texts extended knowledge of China in the Western world

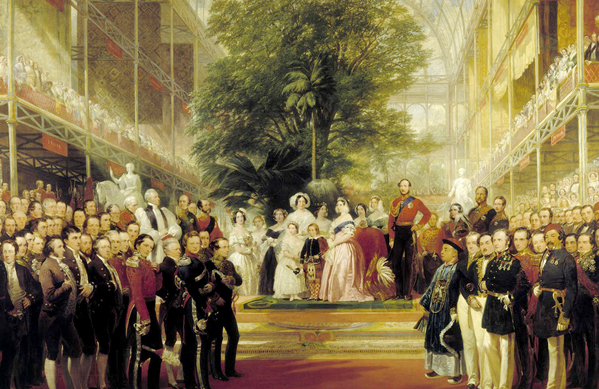

In the painting “The Opening of the Great Exhibition (1851)” by Henry Courtney Selous (1803–90), the identity of the man in Chinese official costume standing in the group with foreign commissioners and chairmen of juries represents the supposed “Lord Xisheng.” Photo: FILE

From tea and dyes to Chinese medicine and the I Ching, how were Chinese knowledge and items of Chinese design and manufacture introduced into Europe?

Tea

The earliest mentions of tea in Western texts appeared in Venice in the 16th century. In 1550, Giovanni Battista Ramusio (1485–1557), a noted Venetian diplomat and geographer, published an important collection of his travel writings, Delle Navigationi et Viaggi (Voyages and Travels).

Chinese tea appears as Chiai Catai (Tea of China) in Delle Navigationi et Viaggi, described by a Persian merchant (named Chaggi Memet). The paragraph containing the tea reference reads: “He told me that all over Cathay they made use of another plant or rather of its leaves. This is called by those people Chiai Catai, and grows in the district of Cathay which is called Cacian-fu (Sichuan Province) … They take of that herb, whether dry or fresh, and boil it well in water. One or two cups of this brew, taken on an empty stomach, removes fever, headache, stomach ache, pain in the sides or the joints, and it should be taken as hot as you can bear it. He also said that besides this it was good for no end of other ailments which he could not remember, but gout was one of them. And if it happens that one feels incommoded in the stomach for having eaten too much, one has but to take a little of this decoction, and in a short time all will be digested.” This book was reprinted in Europe many times, having a profound influence over the European perception of tea.

Traditional Chinese medicine

The Polish Jesuit missionary Michal Piotr Boym (1612–59) was credited with bringing the first knowledge of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to Europe. His book, Clavis Medica ad Chinarum Doctrinam de Pulsibus (Key to the Medical Doctrine of the Chinese on the Pulse), contains an overview of the TCM of the times, including basic notions such as yin and yang and the five phases, essential diagnoses, and treatments such as palpation, acupuncture and herbal medicine.

Boym’s career didn’t fare particularly well. Most of his original manuscripts hadn’t been published before he passed away. After his death, these manuscripts were obtained by a Dutch merchant, among which the texts about TCM were alleged to have been plagiarized by Andreas Cleyer (1615–90), a German surgeon from the Dutch East Indies Company. In 1682, Cleyer’s book Specimen Medicinae Sinicae (Chinese Medicinal Plants) was published with the assistance of a German sinologist named Christian Menzel (1622–1701). It was not until Boym’s colleague Philippe Couplet wrote to Menzel that Boym’s name appeared on Clavis Medica ad Chinarum Doctrinam de Pulsibus as its author, published in 1686. (The authorship of Specimen Medicinae Sinicae is controversial. Existing scholarship has demonstrated that much of the text appears to be the work of Boym. It has been said in Cleyer’s defense that although he did not credit Boym on the title page, neither did he claim authorship. Rather he listed himself as the editor of this book.)

The best known of Boym’s works is the Flora Sinensis (Chinese Flora), published in Vienna in 1656. The book is considered the first description of China’s ecosystem published in Europe, depicting dozens of plants and animals from China. Boym is thereby acknowledged as the “Polish Marco Polo.”

I Ching and Leibniz

The I Ching is believed to be one of the world’s oldest books. The two major branches of Chinese philosophy, Confucianism and Taoism find common roots in the I Ching.

The two-volume works titled Y-King translated by a sinologist named Julius Mohl (1800–76) and published in 1834 and 1839 respectively was the first accomplished translation of the I Ching published in Europe. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a German mathematician and philosopher who developed the binary number system, was keenly interested in the I Ching. In 1701, he mentioned his idea about the binary system in a letter to Joachim Bouvet (1656–1730), a French Jesuit who worked in China. In his reply with a diagram of I Ching hexagrams attached, Bouvet told Leibniz that he found that the concepts and symbols from the I Ching hexagrams corresponded with binary arithmetic. (The I Ching uses a complex binary code in its formation of hexagrams. Yin is notated as a broken line while Yang is notated as an unbroken line. These lines are then used in a set of three to form eight trigrams, which combine to create 64 hexagrams). Inspired by Bouvet’s reply, Leibniz published their conversation about the binary system in scientific journals, extending the influence of the I Ching in the West.

The Keying and “Lord Xisheng”

For the Chinese people, the businessman Xu Rongcun is usually honored as the first Chinese person who attended the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. However, Westerners may be more familiar with another Chinese person who attended the same exhibition, “Lord Xisheng” (Hee Sing).

In August 1846, several British merchants purchased a Chinese junk boat in Guangdong Province, renaming it after the Manchu official Keying (1787–1858), who signed the Treaty of Nanking with Britain following the First Opium War. The junk arrived in London in March 1848. Seeing commercial prospects in the Europeans’ interest in China, the British merchants who purchased the Keying used this junk as a moving museum, exhibiting a large amount of Chinese artworks and its Chinese crew. In order to get public attention, the captain hired a Chinese man and packaged him as “Lord Xisheng,” a Chinese envoy and an official of the fifth rank. Ironically, “Lord Xisheng” was mistaken as a real Chinese official and was invited to the Great Exhibition. He gatecrashed the opening of the Great Exhibition and convinced everyone attending of his value as an important Chinese official. His presence caused quite a stir.

Mysterious green dye

In 1858, a collection of three theses on the Chinese green dye Lo Kao, along with an attached specimen of dyed cotton cloth, was published by Chambre de Commerce de Lyon in Paris.

Before Lo Kao attracted the attention of European textile manufacturers and scholars in 1846, the European green dye in use at the time was produced by mixing blue and yellow pigments. The green dye produced in this way fared badly in quality under bright light. Compared with the European green dye, Lo Kao, made of plants, was of better quality and appeared genuinely green under artificial light. Driven by its great commercial prospect, this dye turned to be quite expensive in Europe, costing 250 Dutch guilders per pound in 1854.

Because of the language barrier and Chinese confidential formula, the Europeans could only import Lo Kao from China. In the 12 years before the publication of the theses, European scientists had done a lot of experiments and research on this mysterious dye, finally figuring out its components and how to produce it.

The article was edited and translated from The Paper.

edited by REN GUANHONG