Vision of Chinese social anthropology shifts from local to global

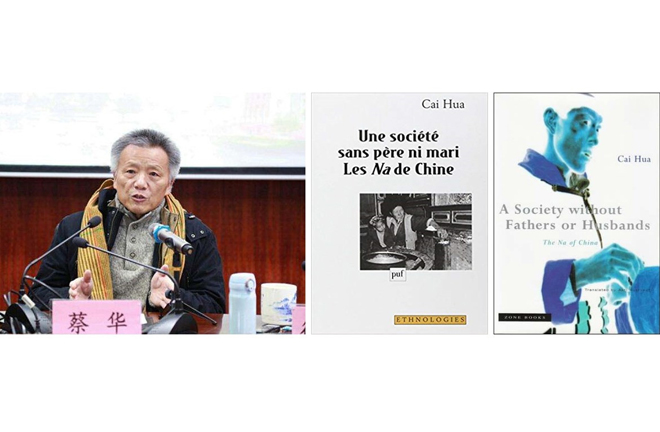

Pictured are Cai Hua, a professor of sociology at Peking University, and his French book Une société sans père ni mari: Les Na de Chine, which was translated into A Society Without Fathers or Husbands: The Na of China in English. Cai was awarded the Grand Prix de la Francophonie Médaille (“Grand Prize of the French-Speaking Countries Medal”) by the French Academy of Sciences for the monumental work. Photo: FILE

Chinese President Xi Jinping first proposed the initiative of building a community of shared future for mankind in 2013. With the expansion of friendly cooperation between China and countries around the world, the initiative has garnered the increasing support of nations and peoples, and it was even included by the United Nations in an important document. As it is gradually translated into action, structuralized and systematized theoretical studies are necessary to provide backing for increasingly rich practices.

As a science to examine different laws of how society functions, social anthropology undoubtedly has a disciplinary advantage in this regard. Shouldering the mission of probing the commonness of human society by studying its diversity, the discipline aligns with the exploration of paths to build a community of shared future for mankind.

The centennial development of Chinese social anthropology witnesses every step the discipline has taken towards its mission and confirms the goals generations of scholars have strived to approach.

Looking back on its developmental course, Chinese social anthropology is rooted in specific contexts of different stages, but in general, it presents a clear diachronic vein. As a modern science, social anthropology in China has evolved in a cycle of 20 to 30 years, beginning with researching rural society represented by villages and communities prior to 1949, then studying ethnic society based on ethnic identification and grand investigation in the 1950s and 1960s, then focusing on folklore to rediscover and understand Chinese society during the reconstruction of the discipline after 1978, and finally embracing the world and responding to universal topics concerning human society today.

Rural society: Beginning

Chinese social anthropology dates back at least to the 1920s and reaches a climax of development in the 1930s and 1940s. The first generation of scholars returning from abroad were the main contributors to related academic research and disciplinary construction. With rural society as the research object, they adopted the fieldwork methodology, laying the groundwork for the development of the discipline.

During this period, Chinese anthropologists carried out extensive field investigations into regions of ethnic groups, including the Han, in the northern, eastern, southern, and southwestern parts of China, accumulating abundant data and generating plentiful research achievements. Examples include Social Organizations of the Hualan Yao Ethnic Group and Peasant Life in China authored by pioneering social anthropologist Fei Xiaotong, The Golden Wing: A Sociological Study of Chinese Familism by Lin Yaohua, and Zhang Ziyi’s The Handicraft Industry in Yicun.

These studies were grounded in fieldwork lasting for more than 4 months and as long as 7 years. To make the results practical, the anthropologists offered detailed descriptions of the rural and regional features of local society, while attending to all aspects of society and the wholeness of culture. In terms of research methodology, they followed the standard of field ethnography that had taken shape in the international anthropological community, establishing the tradition of valuing practice in the infancy of Chinese social anthropology and building a solid foundation for its development.

Ethnic society: Local orientation

In 1949, the People’s Republic of China was founded, while Chinese social anthropology entered the stage of socialist transformation. In the early days after being introduced to China, it was referred to as anthropology or ethnology interchangeably. When institutions of higher learning were restructured nationwide, anthropology as a name for the discipline was abolished in 1952 in favor of ethnology. During the period, the special historical context weakened the rural nature of Chinese social anthropology formed at the beginning of the discipline, and the focus was shifted to “ethnic traits.”

Between 1956 and 1964, a massive investigation of ethnic groups, which was considered a great feat of Chinese ethnology, unfolded in academia. More than 1,400 scholars participated, whose footprints spread across the regions of all ethnic groups in China. The grand investigation finished ethnic identification and defined the basic pattern of 56 ethnic groups in China, laying the basis for the Chinese system of regional ethnic autonomy. Moreover, it inquired into the historical conditions of ethnic societies and collected a wealth of materials comprising documents, interviews, cultural relics and videos.

Starting from 1958, each team of the grand investigation began to compile the Three Series of Ethnic Issues, which were later extended to five series. The compilation work spanned 30 years. Not until the 1990s were all volumes published successively, totaling more than 400 books and approximately 80 million Chinese characters.

The large-scale investigation was different from independent, prolonged studies typical of previous anthropological fieldwork, but the team research enriched the knowledge base of world anthropology to some degree.

Folkloric society: Reconstruction

In 1979, folklorists Yang Kun, Gu Jiegang, Zhong Jingwen and others jointly presented the Proposal of Establishing Folklore and Related Research Institutions, setting a trend for folkloric studies in the 1980s. Chinese social anthropology has entered the stage of reconstruction since then. From the end of the 1970s to the beginning of the 21st century, social anthropologists, with folk customs as a point of departure, reinterpreted local societies by shedding light on many aspects of local ethnic groups and urban life, such as marriage customs, taboos, kinship terminology, rituals and festivals.

This period was marked by a consensus on the research object and methodology of social anthropology, playing a transitional role in the whole development course of the discipline. Then after discussions on such concepts as ethnic groups, ethnology and anthropology, scholars generally held two opinions.

For one, it was held that anthropology should focus on ethnic groups to study the concrete features of each in the processes of their formation, development, change and demise, along with political, economic and cultural interrelations between different ethnic groups and the laws of development of and changes to the relations.

The other group of academics maintained that culture should be the research object of anthropology, arguing that the populace has their own cultural choices in different societies and different social stages. Anthropologists should first discover and describe these cultural forms and then unveil general laws between different cultures.

With debates between divided opinions, scholars gradually reached a consensus on the research object that social anthropology is a science of the different social, not biological, attributes of human beings. As to research methodology, it was made clear that field investigation should be fundamental to the discipline. In other words, social anthropologists should, by observing specific behaviors and activity models of human society directly and for a long term, analyze relations and structures underlying those behaviors and explore their general laws to scientifically explain human behaviors and social activities.

Human society: New era

In 2002, Cai Hua, a professor of sociology at Peking University, was awarded the Grand Prix de la Francophonie Médaille (“Grand Prize of the French-Speaking Countries Medal”) by the French Academy of Sciences for his Une société sans père ni mari: Les Na de Chine, which was translated into A Society Without Fathers or Husbands: The Na of China in English. Based on two and a half years of fieldwork, the book systematically investigates the Na society on the border between Yunnan and Sichuan provinces and redefines the kinship system and the basic structure of kinship through detailed ethnographic portrayals and rigorous theoretical analysis, solving the paradox on marriage and family put forward by French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss more than half a century ago. Academia held that Cai’s achievement signified the second spring of Chinese anthropology and ushered in a new era for the discipline.

During the period, Chinese social anthropology has centered on the four basic topics--kinship, economy, politics and religions--and gradually spawned diverse issues. The vision of research has gradually gone beyond rural, ethnic and folkloric society, with its sights cast on human society.

Different topics in social anthropology share two common features. First, the fundamental principle of field investigation has been wholly or partially inherited. The principle requires more than one year of fieldwork, the use of the language spoken by investigated objects, and genealogical analysis of more than 500 people. Second, some influential serial research achievements were produced, such as the “Field and Discovery” serial ethnography themed on the kinship system, the series on the “Tibet-Yi Corridor” featuring area studies, and the serial studies on “Overseas Ethnography” to export Chinese anthropology, substantially enriching the global vision of Chinese social anthropology research.

In his speech at the General Debate of the 70th Session of the UN General Assembly in 2015, Xi quoted the Book of Rites as saying, “The greatest ideal is to create a world truly shared by all,” to interpret the community of shared future for mankind. The research path of social anthropology from social diversity to the commonness of human society is exactly an exploration of “the greatest ideal” to a certain extent.

After being introduced to China and taking root in Chinese academia, social anthropology has served national decision-making through ethnic identification and investigation and rediscovered and explained local society by means of folkloric research. Today it examines domestic and foreign societies from diverse perspectives. In terms of research vision, its focus has shifted gradually from the rural, ethnic and folkloric features of local societies to the common side of mankind. The disciplinary mission of social anthropology is to seek possible paths for building a community of shared future for mankind by studying different local societies across the world. This is also the unique significance of the discipline in the contemporary era.

Lin Hong is from the Institute of Sociology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

edited by CHEN MIRONG