Poor recording of history hinders study of children’s literature

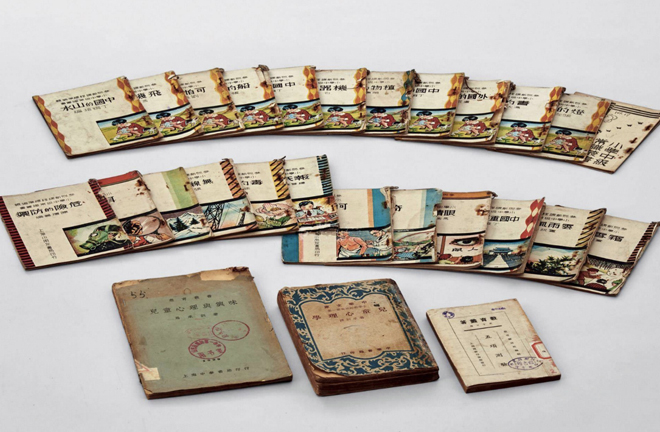

Books of the Republican Era (1912–49) on children’s education, including educator Ge Chengxun’s treatise Children’s Psychology and Interest (Bottom Left) and translation Children’s Psychology (Bottom Center) Photo: FILE

After nearly a century of constant effort, academics have achieved remarkable results in the study of Chinese children’s literature. However, some longstanding problems loom large in the field, including a serious lack of the recording of history.

Lesser-known masters

Over the past century, many scholars have made important contributions to the study of Chinese children’s literature, but for various reasons, quite a few of them are not familiar to later generations. Ge Chengxun, who made a career out of children’s education and children’s literature studies, is one of the forgotten.

In 1934, the Shanghai-based Children’s Book Company published Ge’s New Children’s Literature. Nonetheless, before the prevalence of digital archives and databases, a large number of old books from the Republican Era (1912–49) were neglected. Even professional researchers could hardly get access to them. Hence, there were few words to be found about New Children’s Literature and its author in monographs on the history of children’s literature.

Reading firsthand materials like old books is one of the most reliable and basic paths to approaching and getting a feel of the society at the time. In the 1920s and 1930s, apart from famed scholars like Lu Xun, Zhou Zuoren and Zheng Zhenduo, a host of “strangers” were devoted to the development and construction of children’s literature, such as Hu Huaichen, Yan Jicheng and Ge Chengxun.

In the research of children’s literature, they were either masters of Chinese classics or educational experts. At the same time, in the field, they were only mentioned in a few theoretical pieces. Their brilliance and rich accomplishments were not well known.

Take Ge Chengxun as an example. He wrote the treatises The Psychology of a Girl and Children’s Psychology and Interest, translated Children’s Psychology, compiled An Introduction to Teaching of Different Subjects for Children and The Management of Kindergartens, and published papers in such magazines and journals as Education, Chinese Education Circles and Primary School Teacher.

However, studies about Ge Chengxun have so far been few and far between in the realm of children’s literature. It is difficult to find information about most of his works.

For example, the book One Hundred Songs for Children edited by Ge was referred to in the History of Chinese Children’s Literature authored by Jiang Feng and the History of Chinese Children’s Literature Criticism by Fang Weiping. Book Lists of Folk Literature included Ge’s book in the list for folk songs and ballads, and noted that it was edited by Ge and published by the Children’s Book Company. And that is all. No more detailed information can be found.

In 1935, Ge wrote A Few Specific Measures on Active Supervision, which was published in the 5th and 6th combined issue of Volume 4 of Jiangsu Education. The periodical contained a brief biography of Ge, offering a summary of the educator’s deeds such as designing courses, joining societies and compiling books. This is one of the few pieces of personal information about Ge.

After 1949, reports and writings about Ge were extremely scarce. Only in the supplement of the second issue of Chinese Education in 1960 could his paper “A Study of Curriculum Standards for Primary School,” which Ge wrote in December of 1948, be seen.

In recent years, Ge’s descendants have been committed to organizing and collecting the various writings of their ancestor, attempting to compile them into a collection. Among others, his manuscript Read Me in the Forties is an invaluable document to researchers.

In 1932, Ge served as a lecturer on children’s literature at Hangzhou Normal University. In his autobiography, he said that the Ministry of Education hadn’t yet defined curriculum standards for kindergarten teachers, so he cooperated with the president of the university to draft related courses for the record. He set aside time to gather children’s books and discuss with educators Shang Zhongyi and Luo Disheng to create lecture notes. The modified edition was later published by the Children’s Book Company with the title New Children’s Literature. “This crystalizes the teaching experience I accumulated in the previous half year,” he said.

This text in his autobiography directly related to the writing of New Children’s Literature is of significant value to examining early theories of Chinese children’s literature.

In addition, Ge’s descendants have tried to restore knowledge of his later life by such means as memoirs, in an effort to portray the master of children’s literature from multiple dimensions beyond books, periodicals and texts.

Worrying situation

Ge’s case is representative in current Chinese children’s literature. In other words, it reflects a worrying situation in studies of the history of Chinese children’s literature and the construction of related archives.

In the research on modern Chinese children’s literature, the history is relatively weak, because the exploration and interpretation of issues concerning the history of children’s literature depends on the construction of archives in the area.

Speaking of such, Hong Wenqiong, author of the History of Children’s Literature in Taiwan, lamented that children’s literature has been undervalued, probably because it lacks academic research. Despite a wide research scope, history needs to be prioritized.

Hong’s argument coincides with the view held by older generations of scholars like Wang Yao and Tang Tao that theories originate from history.

While studies of basic theories, writers and their works abound, the scarcity of research on the history of Chinese children’s literature is closely related to the weakness in archive construction and the deficiency of collected historical materials.

Since the 1980s, the beginning of the construction of the history of Chinese children’s literature, such scholars as Hu Congjing and Sheng Xunchang have paid attention to gathering and studying historical documents about children’s literature.

On the whole, however, related efforts were insufficient, since the collected materials were mostly autobiographies and anecdotes about writers.

For instance, the Juvenile & Children’s Publishing House published Children’s Literature and I featuring the memoirs of 29 children’s literature authors, including Ye Shengtao, Bing Xin and Chen Bochui, giving accounts of how they embarked upon the journey of creating children’s literary works.

The Archive of Modern Children’s Newspapers also adopted the approach of collecting materials from witnesses. In the Republican Era, children’s books such as Library for Toddlers, Library for Pupils and A Collection of Lost Works by Masters, which were sorted and published by experts of literature from the Juvenile & Children’s Publishing House in collaboration with The Archive of Children’s Literature and Dolphin Books, represented efforts to rediscover the history of Chinese children’s literature; but more systematic document collection, organization and publication is still needed.

A convenient and feasible approach would be to promptly absorb the latest achievements of academia to break the closed pattern of historical narrative in the field. On Dec. 31, 1921, renowned philosopher and writer Hu Shih delivered a speech titled “Chinese Language Reform and Literature,” in which he mentioned the trend of children’s literature comprising fairytales, myths and stories and how to develop children’s interest in literature.

The speech was later compiled by language expert Guo Houjue and published in the Morning Post Supplement on Jan. 9, 1922.

As a crucial work by Hu Shih, “Chinese Language Reform and Literature” was included successively in collected works of the philosopher, and it is not difficult to find it, but children’s literature researchers have failed to absorb the material. They have often quoted Hu Shih’s article, yet provided the wrong source. Only Jiang Feng’s History of the Development of Chinese Children’s Literature got it right.

Going back to firsthand materials, it is vital to question and correct those views that seem to be conclusions but actually are vague with sources unknown. For example, many writings about the history of children’s literature, including the History of Modern Chinese Children’s Literature written by Zhang Zhiwei, have contended that the column “Children’s Territory” launched in Women’s Magazine in 1921 was an important platform for publishing children’s literature during the May Fourth Period.

A review of the magazine of that year would reveal two mistakes in its claim. First, the column “Children’s Territory” was launched in 1920, not 1921. Second, it was a special column under the “Family Club” section, dedicated to providing children opportunities to publish their thinking and academic achievements, rather than children’s literary works. Therefore, researchers should check the historical materials when studying children’s literature.

Last but not least, efforts should be made to expand the vision of children’s literature research and construct archives covering multiple dimensions. The research focus should be shifted from writers and their works to the past and new theoretical resources.

Furthermore, we should dig out more historically valuable resources to enrich contemporary children’s literature practices. The organization of oral history merits attention. In the community of Chinese children’s literature, there are evergreen experts like Sheng Ye, Jiang Feng and Ren Rongrong. All of them are in their nineties yet remain active in areas of children’s literature creation, criticism and translation. They are not only participants in and constructors of modern children’s literature, but also a “living history” of the development of Chinese children’s literature.

In addition, regarding lesser-known researchers like Ge Chengxun, interviewing their descendants and examining their manuscripts and academic legacies might also help restore or add to history, better representing their significance in the study of Chinese children’s literature.

Hu Lina is an associate research fellow from the Children’s Literature Institute under the College of Humanities at Zhejiang Normal University.

edited by CHEN MIRONG