Experts explore origin of Chinese philosophy

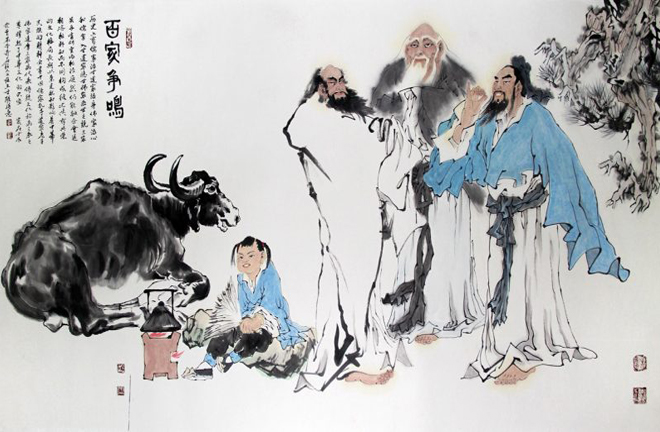

The thoughts and ideas discussed and refined during the period of the Hundred Schools of Thought have profoundly influenced lifestyles and social consciousness up to the present day in East Asian countries and the East Asian diaspora around the world. Photo: Wang Shixiong

Experts shed light on the origin of Chinese philosophy at a forum at Shandong University July 17–18.

Existing scholarship may trace the origin of Chinese philosophy back to the Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) and Zhou (1046–256 BCE) dynasties, the culture of wushi (the officers of prayer), ancient myths and religions, or the thought of Confucius (551–479 BCE) and Laozi (c. 600–c. 470 BCE).

To examine the origins of Chinese philosophy, we must start with the thought and mindsets of our ancient Chinese ancestors, said Wang Xingguo, a professor from the philosophy department at Shenzhen University. Primitive religion, witchcraft-divination and mythology constituted the basic forms of the wu-li (wu meaning shamans or sorcerers and li meaning ritual or propriety) cultural traditions in ancient China and were the starting point and content of Chinese philosophy in the Shanggu times, the early historical times before Xia (c. 2070–c. 1600 BCE).

Ouyang Zhenren, a professor from Wuhan University, took the interpretation of two Confucian classics—the Great Learning and the Doctrine of the Mean—as an example. If one does not refer to the religious traditions and witchcraft traditions in Shanggu or does not see the relationship between the two classics and the history and intellectual development in Shanggu, it is impossible to fully understand the concepts of “manifesting their bright virtue” and “investigating things to extend knowledge” in the Great Learning or “What Heaven confers is called NATURE” in the Doctrine of the Mean. Without knowing about Shanggu, it is impossible to correctly understand the Confucian classics before the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE).

It is generally believed that Chinese philosophy originated during a period known as the Hundred Schools of Thought, which refers to the philosophies and schools that flourished during the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BCE) and the Warring States period (475–221 BCE). However, some scholars have different views on the formation and early forms of Chinese philosophy.

Shen-chon Lai, a professor from the Department of Chinese Literature at Taipei University, argued that neither Confucian philosophy nor Taoist philosophy in the pre-Qin period is the origin of Chinese philosophy. Both of them adhere to the ideological and cultural traditions formed before the period of the Hundred Schools of Thought and have carried out their own ontological interpretations.

Guo Yi, a professor from the philosophy department at Seoul National University in South Korea, said that the late Spring and Autumn period was not an era of formation for Chinese philosophy but a new stage in its development. He said that the period from Shanggu to Shang witnessed the gestation of Chinese philosophy. From Shang to the middle of the Spring and Autumn period—this was the period of creation for Chinese philosophy. The basic components of Chinese philosophy were already completely formed in the elaborations on de (virtue) in the Western Zhou (1046–771 BCE).

Some scholars have questioned Guo’s point of view. Shen Shunfu, a professor at Shandong University, said that philosophy is a worldview and is manifested in an understanding of the greatest and the smallest. The former refers to an overall understanding of the world, and the latter refers to an understanding of the ultimate being or the ultimate source of the world. Since the Tao (the Way, or doctrine) at the time of Zhuangzi (c. 369–c. 286 BCE), the ancient Chinese had begun their own understanding of the greatest being. At the same time, people attributed the origin of all things in the world to qi (vital energy or material force), which is the understanding of the smallest. As such, ancient Chinese philosophy should begin with Zhuangzi and his time.

Before Confucius and Laozi, there was already a more ancient Taoist cultural heritage, and the Tao should be regarded as a kind of ontological thinking and cultural practice, Lai argued.

The participating scholars mentioned that the basic issues and discourses of Western philosophy have been applied to the history and the understanding of Chinese philosophy to a large extent. Lai suggested that the contemporary interpretation of Chinese philosophy must break through the framework of Western philosophy and carry forward the spirit and characteristics of Chinese philosophy.

edited by SU XUAN