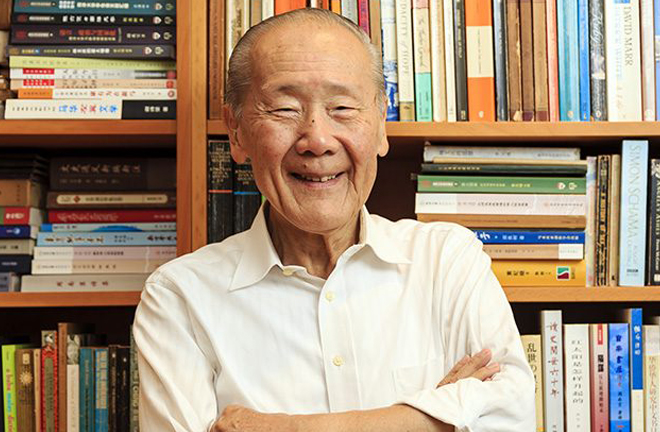

Interview with Wang Gungwu on significance of studying overseas Chinese

Wang Gungwu is a distinguished Australian historian who studies overseas Chinese. He currently works at the Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences of the National University of Singapore (NUS) and chairs the East Asian Institute of NUS. Of Chinese descent, he was born in 1930 in Indonesia. Wang received his bachelor and master degrees from the University of Malaya in Singapore and his doctorate in the University of London. His books include The Chinese Overseas: From Earthbound China to the Quest for Autonomy and Renewal: The Chinese State and the New Global History.

Wang Gungwu is recognized as one of the world’s leading historians on Chinese history and a founder of the study of overseas Chinese communities. He has won the Fukuoka Prize and the Award for Contribution to Chinese Studies. Wang has lived in a multicultural and multilingual environment. The concept of “overseas Chinese” proposed by him has been widely used in global academia.

Zhang Mei: How did you develop your professional concern for overseas Chinese?

Wang Gungwu: My major was history, and my research domains were historical issues. However, I grew up in Southeast Asia. When I went to teach at the University of Malaya, the situation in Southeast Asia was complicated. There was a tremendous change in which the countries were starting to transform from colonies into nations with independent regimes. Under these circumstances, the concept of overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia was bound to change, because these people had to choose between going back to China and staying in foreign countries.

This situation was very different from the colonial period. Nationality used not to bother overseas Chinese, because they were not allowed to apply for English, French or Dutch nationalities. They were still Chinese. They were called overseas Chinese because they didn’t have other nationalities. After the Second World War, however, the colonies became emerging nation-states, requiring those who came from overseas, mainly Chinese and Indians, to decide whether to stay to help the local people and whether to maintain their identity. Some countries gave them time to consider, while some countries forced them to decide immediately. I see this as a very serious question as it affected millions of people. Each family faced the dilemma. When I started to work at the University of Malaya, I had to pay attention to this issue and seek ways to tackle it.

There was another reason. Prior to World War Two, all the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia were regarded as Chinese and more or less the same. But I began to notice that things were not that simple. In fact, the overseas Chinese in different colonies varied in terms of backgrounds, environments and life experiences. Their hometowns were located in different provinces. Most of them came from Guangdong and Fujian provinces, and some from Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region and other places. What’s more, their descents, after two or three generations, could show remarkable differences despite that they all migrated from China or even from a same place. For example, Cantonese people who went to Vietnam and Malaysia could be different after one or two generations. Their customs, languages and educational backgrounds could become divergent even if they came from the same place. This made me particularly interested in the study of overseas Chinese.

Zhang Mei: What have you found after so many years of research?

Wang Gungwu: After becoming interested, I began to study how and why overseas Chinese were different. For example, Spain and the United States cast different influences over their colonies, and Thailand was something else entirely. Unlike Singapore and Malaysia, Thailand had not been colonized by the United Kingdom or France. For example, Spain ordered people in the Philippines to believe in Catholicism after it occupied the country. Over the following decades, all Filipinos converted to Catholicism. Coming from Southern Indonesia, some of them who were Muslims had to convert. Chinese would suffer a lot if they didn’t follow suit, because the Spanish colonial government wouldn’t allow the Chinese to go about large-scale business but small business, nor could they purchase houses or land if they refused to declare faith. Chinese people could only go about small business. Therefore, most Chinese had to worship Catholicism.

There was another problem that forced the Chinese to declare faith. There were rules in China that women could not go abroad, and only men alone could leave the country. Therefore, the ethnic Chinese men had to start families with local women. Filipinos believed in Catholicism. If you were not a Catholic, you couldn’t marry a Filipina wife. The Chinese men followed in Catholicism as they had no other choice to survive. Two or three hundred years later, the entire Chinese community in the Philippines had developed into a Catholic Chinese community. After several generations, their descendants all became Filipino.

Zhang Mei: What solutions have overseas Chinese found to deal with the situation in the Philippines?

Wang Gungwu: Of course, the Chinese had solutions. For example, the people from Southern Fujian Province established a new method when they couldn’t bring their wives or children to foreign countries. They needed to first start a family before going to the Philippines. Many businessmen needed to raise one or two children first, or they would be asked to come back and have some children. In other words, they could marry local women and believe in Catholicism in foreign countries, but their home was still in Fujian. These Fujian people carried on their own customs and habits in this way as a policy and a strategy. Ot4erwise, the family roots would be destroyed. This solution could continue their family and business relationship at the same time. China and the Philippines were trade partners back then, so a businessman could shuffle between his two families. Their children born in foreign countries didn’t necessarily learn how to do business, and had no opportunity for receiving education. If possible, the Chinese men could bring their sons back to China to study. Only in this way could they pass the business to their sons when they grew old, so these children also knew a little Chinese.

This strategy was quite useful. It had evolved into a mechanism due to its effectiveness despite the complicated situation that had taken shape over hundreds of years. This mechanism helped balance a businessman’s bonds with both families. After a few generations, however, the children (Chinese descents) who stayed in the Philippines naturally became localized. They believed in Catholicism, just like the Filipinos, but from the perspective of pedigree, they were still Chinese. People also got married within the Chinese community due to their reluctance to marry the indigenous Filipinos, so the social form of the Chinese community continued for a long period. However, many of them were no longer overseas Chinese as they changed their nationality. This interested me in particular.

Zhang Mei: Since the founding of the new China, especially since the reform and opening up, overseas Chinese have made major contributions to China’s modernization. What’s your take on their efforts?

Wang Gungwu: Overseas Chinese have made huge contributions to the development of China in the past 41 years. At the outset of the reform and opening up, the West knew little about China, and foreign investors didn’t have the courage to enter the Chinese market as a pioneer. How could China participate in international economic activity? China could only rely on overseas Chinese, because transnational migration and re-migration allowed Chinese overseas to experience and embrace Western modern technology and modern civilization. They became one of the driving forces of China’s modernization. Shortly after his visit to Singapore, Deng Xiaoping proposed that the first step of China’s opening up to the outside world was opening the market to overseas Chinese, and he came up with the idea of establishing a special economic zone. It turned out to be a remarkable initiative.

Overseas Chinese’s success in aiding China’s economic construction has attracted foreign investment in China, promoting China’s opening up to the outside world. This also led to the later proposal of the Chinese government to build a socialist market economic system. Therefore, many foreign observers have expressed their admiration for the contributions of overseas Chinese to the reform and opening up. The large number of overseas Chinese has stimulated the prosperity of the Chinese economy. They are one of the key factors in the success of China’s reform and opening up.

Zhang Mei: Presently, the study of overseas Chinese touches on various aspects, such as economics, science and technology, culture, education, and community. What do you think is worthy of attention?

Wang Gungwu: The issue of overseas Chinese is complicated. It is a good sign that many people are exploring it. If scholars can study it thoroughly, the officials who make related policies can also better their understanding of overseas Chinese. Making policies without due consideration could result in misunderstanding. Overseas Chinese will fail to understand correctly. Foreign countries will misinterpret the policies as well, which will hurt diplomatic relations between countries. Why should China establish the Ministry of Foreign Affairs? A country can only make good policies based on a good knowledge of foreign countries’ circumstances. Otherwise, the policies must be unpractical. Therefore, it is insufficient to develop our own views. It behooves us to know more about the situation of other countries and the arguments of foreign scholars.

There are more and more scholars studying overseas Chinese and ethnic Chinese. It is very useful and even crucial to observe the relationship between the history of overseas Chinese and China’s social and political development. Overseas Chinese have become more important as China now implements the Belt and Road initiative and more companies seek to enter the global market. In particular, the surge of new Chinese immigrants can also play an important role. New immigrants are different from Chinese descents and local Chinese. If you can’t tell the difference, it is easy to cause misunderstandings. Even Chinese with foreign citizenship misunderstand each other. Some Southeast Asian countries hold a prejudice against local Chinese. Where there is misunderstanding, more problems will emerge. Future study of overseas Chinese should focus on not only the lives of Chinese in foreign countries, but also the impact on them by China and Chinese policies.

edited by MA YUHONG