Animal statues witness Forbidden City’s history

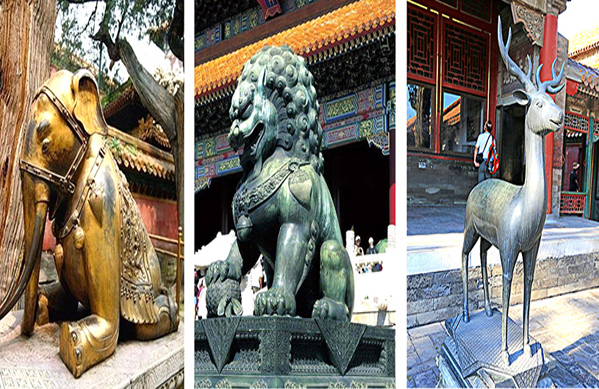

Left to right: a kneeling elephant, a guardian lion and a bronze deer Photo: FILE

The Forbidden City is known not only for its aesthetic value but also its cultural significance. Various animal statues bear witness to the past greatness of this city.

Kneeling elephants

In the north of the Imperial Garden inside the Forbidden City, there is a pair of bronze elephants kneeling face-to-face. Both elephants are 1.1 meters high, 1.6 meters long and 0.8 meters wide. Made in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), these two gilded elephants look down on the ground with their trunks rolling up and kneel in homage to visitors, as they once did to the imperial residents of the Forbidden City. The elephant is considered a symbol of good fortune because of its power, dignity and reputation for peace. It also symbolizes the divine in Buddhism. All of the animal’s traits, derived from traditional culture, made the elephant popular within royal dynasties.

There are several reasons why the kneeling elephants appear in the Forbidden City. Because of its massive body and huge power, the elephant is favored as a symbol of military power in the imperial residence. Historical documents show that these giant animals were incorporated into military use from the Shang Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty. During the Ming Dynasty, Yunnan Province was rich with elephants. Specific institutes for training elephants for military use were established, providing the state with a consistent supply of war elephants. Therefore, the statues of the elephants within the Forbidden City can be regarded as imperial guards.

The elephant also played an important part in the protocol of the imperial procession. Marco Polo (1254–1324) mentioned in his journal that there were 5,000 elephants marching in the royal parade during New Year’s Day in the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). This shows that since the Yuan Dynasty the elephant has been used for rites and ceremonies. The Qing (1644–1911) adopted the same tradition and kept elephants in certain institutes. In some major imperial ceremonies, such as a new emperor ascending the throne or a royal wedding, these elephants would appear in noticeable parts of the Forbidden City as lubu (bodyguards of the nobility).

The dressing and decoration of the kneeling elephants is similar to that of the elephants that were recorded serving in emperors’ imperial carriage processions. Therefore, this pair of kneeling elephants, which pose like they are receiving an emperor, may represent obedience to imperial power.

Guardian lions

The pair of giant guardian lions standing at the entrance to the Gate of Supreme Harmony is the largest pair of guardian lions that exist in China presently. There is no inscription on the lions. They may have been produced during the Ming Dynasty. The lions are finely cast in bronze with smooth surfaces and exquisite details.

Different from the guardian lions in front of the Gate of Heavenly Purity, the statues in front of the Gate of Supreme Harmony stand with ears upright, as if they are alert to their environment. The design that shapes the heads and bodies of the guardian lions into spheres while making the statues erect on square bases reflects a prevailing belief in ancient China that the Earth was flat and square while Heaven was round—an assumption virtually unquestioned until the introduction of European astronomy in the 17th century. Each lion is 2.4 meters high, sitting on a 0.6-meter-high bronze base, positioned on a xumi base (xumi bases were introduced from India and originally used as bases for statues of Buddha) made of white marble. On the huge xumi base, there are various carved patterns, including a xinglong pattern (dragon-shaped pattern), lotus petal pattern and a wan hua shou dai (a special pattern symbolizing an everlasting reign).

These guardian lions consist of a male standing on the left and a female on the right. The male leans his paw upon an embroidered ball, representing supremacy over the world, while the female plays with a cub, symbolizing nurture. The most notable feature of the lions is the lumps on their heads, representing their curly hair. The number of the lumps is not random. In fact, the Chinese used the number of lumps to indicate the ranks of the officials. Lions with 13 lumps, the highest number, belonged to the houses of first grade officials, and as the rank of the official went down each grade, the number of lumps decreased by one. The officials whose rank was below the seventh grade were not allowed to have guardian lions at the entrance of their houses. However, each of the guardian lions in the Forbidden City has 45 lumps on its head, because they guarded the house of the emperor, who was traditionally called jiu wu zhi zun (the supremacy over nine and five; in the I Ching, nine and five refer to the lines of hexagrams that represent the throne). The number of the lumps is derived from the product of nine and five.

Bronze deer

The Palace of Gathering Elegance (Chuxiu Gong) seems to be an ordinary palace located in the north of the Six Western Palaces in the Forbidden City. However, it used to be the most important residence of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908), one of the most influential women in imperial China. From when she stepped into the Forbidden City (1852) until she ruled China behind curtains, Cixi had spent most of her lifetime in this palace.

There is a pair of bronze dragons and a pair of bronze deer at the foot of the steps outside the Palace of Gathering Elegance. Produced in 1883, these bronze deer were 1.6 meters high, 0.3 meters wide and located on a 0.22-meter-high bronze base. The deer look gentle and calm, revealing a touch of peace and feminine charm.

There are several guesses that can be made at the reasons for putting this pair of deer in front of the Palace of Gathering Elegance. Some associate it with three important events that occurred around the year of 1883.

The first one was that Cixi moved back to the Palace of Gathering Elegance from the Palace of Eternal Spring (Changchun Gong) in 1884 to celebrate her 50th birthday. In the book named Gongnü Tanwang Lu (the memory of a palace maid, literally), He Ronger, a palace maid who had served Cixi for eight years in the Forbidden City, believed that Cixi moved back to the Palace of Gathering Elegance out of her love for her husband and personal experience there. Cixi had lived in this palace for many years after she married the Xianfeng Emperor at age 17. The palace was full of memories for the young couple. Besides this, Cixi gave birth to her son in this palace, who then became the Tongzhi Emperor, paving her way to the height of supreme power over the nation.

The second event was that Cixi had just recovered from a liver ailment in 1883. The third event occurred in 1884, when Cixi used China’s loss in the Sino-French War (1884–1885) as a pretext for getting rid of Prince Gong and other important decision-makers in the Grand Council. Cixi then consolidated control over the dynasty.

Based on Cixi’s experience and the cultural meaning of deer in China, there are several other possible reasons why these deer were placed there. The deer was a symbol of romance in ancient China. Before a man married a woman, it was customary for the groom to send two pieces of buckskin as a betrothal gift to the bride’s family. Perhaps Cixi wanted to commemorate her love for her husband. The other reason may have lain in the pursuit of health and longevity. Since the Han Dynasty, the ancient Chinese have believed that venison was beneficial to health. Eating antler and venison and drinking deer blood were important in the regimen followed by the royal family of the Qing Dynasty. Some also associate deer with a longing for power, as chasing a deer symbolized fighting for the throne in traditional culture. The last reason lies in the ancient belief that the deer was an auspicious animal delivering good fortune to mankind. Meanwhile, the Chinese character for deer sounds like the character for “lu,” which means wealth and prosperity.

This article was edited and translated from Guangming Daily. Zhou Qian is from the Institute of Gugong Studies at the Palace Museum.

edited by REN GUANHONG