Silk texts on numerology in Mawangdui tombs of unique value

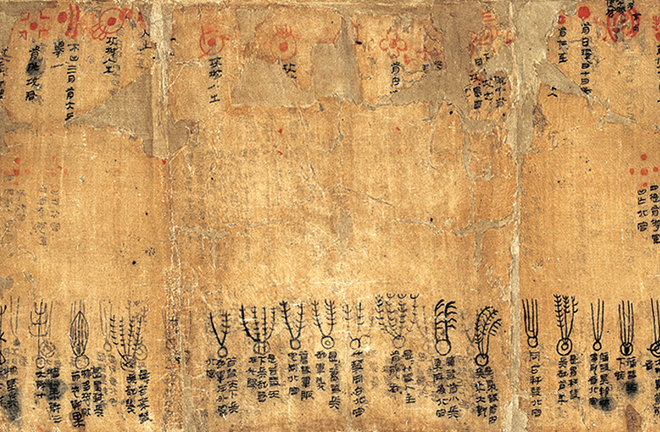

This manuscript from Mawangdui Tomb 3 concerns divination through the interpretation of astrological and meteorological phenomena. Photo: HUNAN MUSEUM

Silk manuscripts on numerology such as Punishment and Virtue (Xingde) Copies A, B and C; Yin Yang and the Five Elements Copies A and B; and Traveling Divination Techniques (Chuxing Zhan) were unearthed from Mawangdui Tomb 3 in 1973, which is located in a suburb of the modern city of Changsha, Hunan Province. Due to multiple factors, the compilation of these silk manuscripts has been far behind that of other documents from the same tomb.

However, after the 40-year effort of three generations of scholars, this batch of records was finally published in 2014 by Zhonghua Book Company in the eight-volume Collection of Silk Texts from Changsha Mawangdui Tomb. It is by far the only collection of numerology books published with their complete texts and based on the scientific excavation of distinguished noble ancient tombs, thus of unique academic value.

Intricate noble almanac

More than 3,000 objects from the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–25 CE) were found in extraordinary condition, representing the highest levels of workmanship. Among the three Han tombs, Tomb 2 belonged to Marquis Li Cang, administrator of Changsha at the beginning of the Han Dynasty, while Tomb 1 belonged to the wife of Li Cang, Xin Zhu; and Tomb 3 was for Li Xi, the son of Li Cang. Some scholars argue that Tomb 3 was for the brother of Li Xi. Either way, these tombs were for an elite ruling family in the early Han Dynasty.

Marquis Li Cang, a nobleman who governed an area of 700 households in Changsha, was one of the founding persons of the Han Empire. He was granted the title of Marquis during the reign of Emperor Hui (r. 194–188 BCE) and ranked some 100th among marquis.

Such family tombs for high-ranking local officials are rare. Documents unearthed are even more priceless. Numerology is a kind of applied skill and knowledge. Due to the different identities of users, its function and purpose vary, and social class is a strong factor. The numerology book the nobles used during their lifetime was different from that of ordinary people.

At present, most of the literature on numerology passed down from the pre-Qin era consisted of calendars, similar to almanacs, offering a time or location reference for the common people regarding marriage, food, clothing, housing and other daily affairs. They reflect ordinary people’s production and lifestyles.

In contrast, the silk manuscripts of Punishment and Virtue and Yin Yang and the Five Elements uncovered from Mawangdui tombs were for the rich and powerful, and they contain astrological and divination recommendations for successful military conquests. Also, the techniques of earthwork and sacrificial ceremonies described in these texts were far more complicated than those in a daily-use almanac. After all, building a palace or a noble tomb, or praying to the gods, were serious state matters in ancient times.

In addition, the numerological interpretations of these silk manuscripts are more abundant than those of a general calendar. Both the basic theory and use were more complex. If an almanac could be regarded as the common knowledge of science and technology, then the numerology texts unearthed from Mawangdui are more like national defense technology, representing the forefront of science and technology at that time, which undoubtedly has great academic value.

Compilation techniques

Among mausoleums of the same period, only the tomb of Xiahou Zao, the 2nd Marquis of Ruyin of the Western Han Dynasty in Fuyang, Anhui Province; the tomb of Wu Yang, the first Marquis of Yuanling, in Huxishan, Hunan Province; and the recently discovered tomb of Liuhe, the grandson of Emperor Wu and the Marquis of Haihun, near Nanchang in Jiangxi Province, can stand at par with the Mawangdui Han tomb in terms of the status of the occupant, its scale and the relics unearthed.

Though the value of the numerology literature from the other three tombs may not be inferior to that of Mawangdui’s literature, they are unlikely to be completed and published soon, due to various reasons such as poor preservation, difficulty of interpretation, or having been studied for only a short time. The silk manuscripts of Mawangdui tomb may be able to enjoy the honor of being the only fully published texts of their kind for a long period.

The publication of the complete unearthed documents is of significance. Previously, when Punishment and Virtue and Yin Yang and the Five Elements were not yet published in their entirety, it was impossible to explore their relationship from the traces of fragmented and incomplete chapters.

Now seeing the full picture of the silk manuscripts, the complex and systematic connections among these lost texts can be revealed. To be specific, part of Punishment and Virtue Copy A was revised according to Copy C. Yin Yang and the Five Elements Copy B is the integration of Yin Yang and the Five Elements Copy A and Punishment and Virtue Copy A and C. Punishment and Virtue Copy B was transcribed according to the content of Yin Yang and the Five Elements Copy B in the framework of Punishment and Virtue Copy A.

Based on the same set of mathematical theories, these lost books of numerology were transcribed one after another in the late Qin and early Han dynasties. They are sample manuscripts in revision and adaptation, and contain constantly developing and changing specialized technical knowledge. Through them, we can revisit the ancient people’s dynamic process of compiling such technical documents, recover their transcription methods, and observe their way of thinking.

At the same time, complete publication is important for the recovery of damaged manuscripts, because the more complete the publication it is, the more likely the damaged parts can be filled in based on the systematic rules of mathematical theory. There are many numerology images in Punishment and Virtue and Yin Yang and the Five Elements. Though some of them are seriously damaged, they can still be remade according to numerology rules.

Through the rich graphic information provided by the silk manuscripts, it can be further concluded that the same numerology can have three forms of expression: image, graph and text. In the process of text transcription, ancient people would choose different forms of expression, according to different uses. This is a new understanding of ancient mathematical document transcription.

Reference for previous discoveries

The unique value of the numerology texts unearthed from Mawangdui could also be attributed to the tombs’ having been discovered intact and then excavated using modern archaeological methods. Scientific archaeological excavations have enabled important information to be preserved. This authentic archaeological evidence could corroborate the silk manuscripts, which greatly improved the academic value of these lost texts.

From Mawangdui Tomb 2, three seals marked “Li Cang,” “Marquis of Dai” and “Prime Minister of Changsha” were discovered. From Tomb 3, a seal marked “Li Xi” was found. Through these pieces of evidence, we can determine the identity of the tomb owners and their living areas. Bamboo and wooden strips from Tomb 3 helped calculate when the tomb was buried, the 12th year of Emperor Wen (r. 179–157 BCE).

Yin Yang and the Five Elements Copy A records the chronology of Qin Shi Huang (r. 221–210 BCE). Punishment and Virtue Copy A holds the chronology of Emperor Gaozu (r. 206–195 BCE), while Yin Yang and the Five Elements Copy B contains that of Empress Lü (r. 187–180 BCE). Using this information, we can not only build a timeline of the transcription of these manuscripts but also determine the time when they were used.

With clear dates, locations and figures, the historical background of these lost texts is not difficult to reimagine. For example, the chronology of Qin Shi Huang in Yin Yang and the Five Elements Copy A was specially notated by the users of the manuscript under the relevant words, so as to check whether these divinations were consistent with the actual situation of the unification war of Qin. The chronology of Punishment and Virtue Copy A is related to the battle of the Han military against the prime minister of Dai, at that time Chen Xi. From this clue, we can know that part of the content of Punishment and Virtue Copy A is based on this particular fight. If it weren’t for archaeological excavations, revealing the history behind these texts would not have been easy.

The lost texts on numerology can also be used as a criterion to distinguish false unearthed documents. As we know, the collection of Tibetan-Chinese slips stored in Peking University is likely to come from high-level tombs, in terms of form, structure and content. Unfortunately, these bamboo slips are not from scientific archaeological excavations, so some scholars have always doubted their authenticity. In Yin Yang and the Five Elements Copy A, there is a chapter from the long-lost Geomancy, which is very similar to the Tibetan-Chinese slips stored in Peking University, proving the authenticity of the later.

Cheng Shaoxuan is an associate research fellow at Fudan University.

edited by CHEN MIRONG