Modern writers find heroes and humans in the ordained

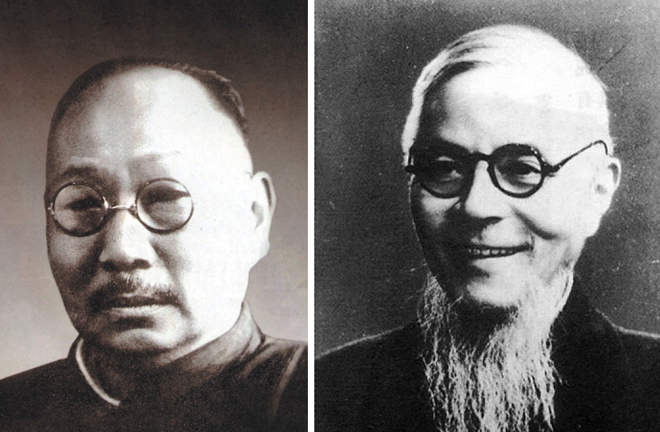

Xia Mianzun (Left) and Feng Zikai (Right), major figures of the White Horse Lake Writers Group Photo: FILE

The revival of Buddhism in the late Qing Dynasty led many modern Chinese writers, particularly those from Zhejiang Province, to write about monks and nuns, exemplified by such authors as the Zhou Brothers (Lu Xun, the pen name of Zhou Shuren, and his younger brother Zhou Zuoren), Yu Dafu, Xu Zhimo, Xia Mianzun, and Feng Zikai, to name just a few. Such writings constitute a unique scene in the landscape of modern Chinese literature.

Valuing personality cultivation

Stressing that the world is miserable, Buddhism aims to guide all living beings to liberate themselves. In the process of liberation, spiritual practice and the cultivation of personality are critical. To that end, the readiness to devote, the adherence to one belief, and the spirit of enduring hardships are must-have qualities. Eminent monks either deliver all living creatures from torture, promote Buddhism perseveringly or value the cultivation of a noble character, so they made excellent subjects for modern writers in Zhejiang.

Different from Liang Qichao and Zhang Taiyan, who attempted to save the nation from subjugation by means of Buddhism, Lu Xun drew inspiration from the religion. He argued that Buddhists’ concentration on belief and their spirit of fighting for belief are encouraging to the people.

In the preface to young poet Ye Yongzhen’s poetry collection Short Ten Years, Lu Xun referred to stories of Buddha Sakyamuni cutting his flesh to feed an eagle and another Buddha giving his body to a tiger so she could feed her starving cubs, praising their selfless deeds highly.

In his “Essay from a Cool Morning,” he mentioned a plan to write a history of famous people, similar to On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History authored by Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle, and he included ancient eminent monk Xuanzang, a unique figure in history, in the plan.

In his article “Have the Chinese Lost Their Self-Confidence?” he said no to the question based on stories of monks Faxian and Xuanzang, commending their firm belief and spirit of self-sacrifice in their quest for Buddhist texts, lauding them as the “Backbone of China.”

While Lu Xun advocated personality cultivation by citing examples of ancient monks, writers of the White Horse Lake Writers Group, an important school of literary creation in the early 1920s that consisted of such well-known modern Chinese writers as Zhu Ziqing, Xia Mianzun, Zhu Guangqian and Feng Zikai, tried to build the image of modern monk Master Hongyi to enlighten the general public.

Xia Mianzun, in particular, produced quite a few stories on Master Hongyi. In “Master Hongyi: Pabbajja,” Xia retells Hongyi’s process of becoming a monk. Born in a banking family, Hongyi gave up his affluent life nonetheless, wearing ragged robes and eating vegetable roots to propagate Buddhism and its code of conduct.

Xia’s “In Memory of the Senior Who Liked the Setting Sun” elaborates on Master Hong Yi’s strong aspiration to save the world and his lofty spirit of self-sacrifice. Around the time when Japan invaded China and occupied Xiamen, Fujian Province, in 1938, Master Hongyi continued to propagate the Dharma in surrounding cities like Zhangzhou, Quanzhou and Hui’an, even expressing a willingness to die for the motherland.

Feng Zikai’s “Appeal of Dharma” represents Master Hongyi’s quiet and peaceful state of life and his wise and merciful charisma. In “Talking to Youths About Master Hongyi,” he portrays the eminent monk as a highly self-disciplined and earnest man.

Generally, the White Horse Lake Writers wrote about the self-disciplined and altruistic Master Hongyi to provide a role model of noble character for the public.

Seeking fun from life

Modern writers in Zhejiang also tried to highlight the attitude of monks and nuns who always sought fun from life. Yu Dafu’s fiction Monk Piao’er describes a secluded monk who lives his life with an aesthetic style. Monk Piao’er has brilliant experiences yet lives a simple life. The detail of his appreciation of the moon underscores Monk Piao’er’s reclusiveness and grace.

In the essay “Flowerbed,” Yu recalls a stoic, austere and detached nun. Her demureness was like that of a tranquil flowerbed, leaving a deep impression on Yu. The flowerbed memory of the author is a metaphor for staying away from evil karma. His different moods before and after going to the flowerbed signify his aversion to a mundane life and craving for fun.

The White Horse Lake Writers depicted Master Hongyi not only as an upright and down-to-earth holy monk but also as an individual who could find good within everything in life. In the preface to Zikai Cartoons, Xia Mianzun wrote, “In the eyes of Master Hongyi, there is nothing in the world that is not good.” He admired Master Hongyi for his attitude towards life: There is always fun in life whether you are sad or happy. “Leave aside the religious aspect, he could even reach that state in trivial daily life. Does he not make life artistic?” Xia said.

In “Talking to Youths About Master Hongyi,” Feng Zikai first sheds light on Master Hongyi’s artistic life before he was ordained as a monk. Even after he entered into Buddhism, he didn’t neglect practicing calligraphy, and he often wrote scriptures and the names of Buddha by hand to propagate the Dharma. Despite the difficulty of observing Buddhist discipline, Master Hongyi never forgot to seek pleasure from art.

Zhu Guangqian, a crucial advocate of the “making life artistic” theory, held that there are two types of people in the world who are least artistic. The first type consists of materialistic persons and the second type hypocrites. Utilitarian and hypocritical, they go with the wind and live a dull life. Art is a fountainhead of life. It can turn vulgarity into elegance and resist dire straits.

Modern Zhejiang writers largely agreed with Zhu. Yu Dafu maintained that art and life are inseparable, while Xia Mianzun and Feng Zikai sought to derive pleasure from life in every moment to get rid of their sins. Therefore, they expounded on the life interests of monks and nuns primarily to rebel against philistinism and achieve self-redemption in an aesthetic fashion.

Chasing humanity’s freedom

The secularization of monks and nuns is the most salient feature of the works of the modern Zhejiang writers. They deconstruct the mysterious halo of Buddhism to express their pursuit of and yearning for humanity’s freedom.

In the essay “My First Master,” Lu Xun endows a monk with rich human nature, jocularly depicting the secularized Master Long, abbot of the Changqing Temple. The monk has a droopy mustache, helps beat drums and gongs in folk operas and even has a wife along with children, as if he were simply a layman with a shaved head.

Besides Master Long, the essay also portrays Third Brother, a lecherous married man. “When ‘I’ mocked him that monks should follow monastic rules, he yelled, ‘If monks don’t have wives, where will little bodhisattvas come from?’” His yell suggests the author’s understanding of real human nature.

In Zhou Zuoren’s essay “Letters from the Mountain,” monks dry Chinese toon leaves and raise chickens every day. Sometimes they get drunk and quarrel over trifles. His frank writing about monks’ secular life reveals their true human nature.

Similar to the Zhou Brothers, Shi Zhecun wrote on the secularization of monks and nuns. He rebuilt secularized images of Master Hongzhi and Great Master Huangxin from a human perspective.

In Shi’s novel The Pabbajja of Master Hongzhi, the master hangs a brightly lit lantern in the middle of the street when night falls, regardless of wind or rain. He seems to illuminate it for all living creatures, but actually his purpose is to brighten the road for his ex-wife.

In Shi’s other novel, Great Master Huangxin, the protagonist has two failed marriages and even performs in the theater before converting to Buddhism, later becoming abbess of the Miaozhu Nunnery. The nunnery is increasingly busy and becomes famous in areas east of the Yangtze River. Great Master Huangxin vows to cast a big bell made of refined copper, but she fails eight times in a row. Not until after she jumps into the furnace does the casting attempt succeed.

On the surface, her jump into the furnace is a sacrifice to Buddhism, but in fact, it is out of her disappointment and shame after finding out her ex-husband is the donor. As the author said, “Great Master Huangxin is divine in the mouth of storytellers, but human under my pen. She knows thoroughly about karma, but she is a human being anguished by the disillusion of love.” Through the conflict of divinity and humanity, Shi Zhecun reveals the subconscious desires and instincts of monks and nuns.

The secularization of monks and nuns symbolizes the shift from divinity to humanity, which aligns with the humanization of Buddhism in Jiangnan (regions south of the Yangtze River) at the time, while conveying the authors’ intricate exploration of human nature.

Zhu Jianxin and Zhu Jiaying are from the School of Humanities at Hangzhou Normal University.

(edited by CHEN MIRONG)