Unreleased Nanjing Massacre archives made public

Xinhua

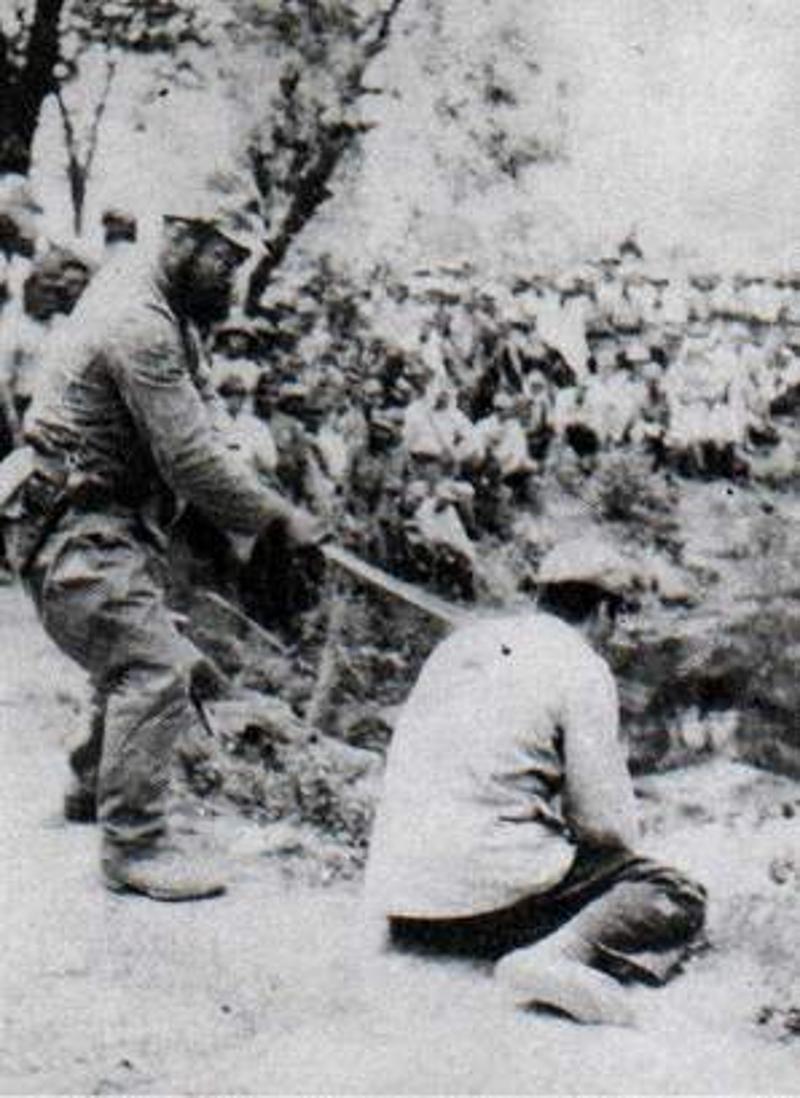

A Japanese solider trying to kill disarmed captives and civilians during the Nanking Massacre

For the first time, the Nanjing Archives has officially released facsimiles of 183 volumes of archival material from the Nanjing Massacre.

“The mass murder committed by Japanese troops in Nanjing stands as a calamity in the history of humankind—a traumanot for only the people in Nanjing but also the whole world,” said Wang Han, deputy director of the Nanjing Archives, in an interview on February 13, two days after the release of the archives. “Currently some Japanese politicians and right-wing extremists outright deny that the massacre happened. This is blatant disregard for historical facts and a challenge to humankind’s conscience. As the victims, the Chinese people of course deplore and oppose such outrageous behavior. The people of Nanjing are extremely indignant.”

Among the materials in the archives is evidence of the Japanese troops’ atrocities, refuting claims by right-wing Japanese that the massacre did not happen, Wang noted.

Consisting of documents collected between 1937 and 1947, the materials were takenover by the Nanjing Military Control Commission after the liberation of China in 1949 and printed as historical documents. This is the first time that the facsimiles have been released tothe public. The archives include articles composed by civilians and presented to various organizations and institutions, records of how charity groups like Chongshan Tang and Puyu Tang helped bury the bodies of victims and provided relief to refugees, statistics on the situation of refugee seekers and files on the establishment of areas of asylum under the Wang Jingwei puppet regime, as well as correspondence, reports and statistics related to investigation into the Japanese atrocities.

The local prosecutor’s office in Nanjing kept detailed records on the investigation process, the enemies’ atrocities, the perpetrators and related material. All of this material was compiled into a report by the office, which also included annotations of the investigator’s comment and suggestions. Detailed of the report are the efforts of Chongshan Tang and the Red Cross tobury the bodies of the victims during and after Japanese troops were committing the massacre. Chongshan Tang worked for consecutive four months and buried 112,267 bodies, and the Red Cross buried 43,071 bodies over the course of sixth months.

After the war, the Nanjing government established several investigation committees under the temporary city council to address the enemy atrocities in Nanjing, atrocities during the massacre, and the city’s losses during the war. These investigations revealed the Japanese troops’ savagery, including massacre, rape and looting and destruction of Nanjing’s natural environment and historical and cultural legacy, noted Xia Bei, director for the Department of Archive Collection and Use at the Nanjing Archives.

Elaborating on the committees’ investigation processes, Xia explained that they were guided and supported by international unions against war crimes. The resulting reports were widely disseminated to increase public awareness, Xia added, noting that the investigators followed strict procedures and that the reports had legal effect.

“Archives are true historical records. By making these archives public, we aim to let truth speak for itself and refute the right-wing extremists in Japan. Meanwhile, we also hope to tell people that we should never forget our history. We should cherish world peace and make sure we never allow such tragedies to occur again. As staff of the archive, this is our responsibility and obligation,” affirmed Wang Han.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 560,February 17, 2014

Translated by Jiang Hong

Revised by Charles Horne