Chinese culture inspired Enlightenment thinkers

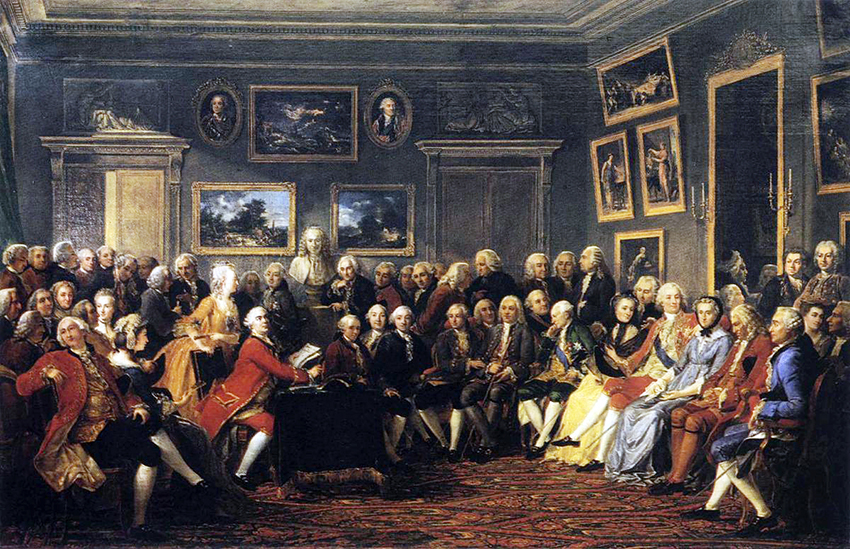

This is the “First reading in 1755 of Voltaire’s L’Orphelin de la Chine in the room of Madame Geoffrin” by Anicet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier. The play was adapted from Joseph Henri Marie de Prémare’s translation of The Orphan of Zhao, a thirteenth-century Chinese play. Photo:WIKI

In recent years, an increasing number of scholars have moved beyond the traditional perspective of the Eastward spread of Western learning and developed a strong interest in the Westward spread of Chinese learning. Their research re-narrates the history of cultural exchange between China and the West.

According to academic research, information about China began to spread Westward before the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE).

Marco Polo, who visited China in the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), set off an Oriental fever in Europe with The Travels of Marco Polo.

However, before the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, cultural and historical information of China recorded by Western businessmen, travelers and envoys was little more than casual observations or subjective impressions, said Ren Zengqiang, director of the Research Office of the Project on Collecting Global Chinese Books at Shandong University.

During the Wanli Period (1572–1620) of the Ming Dynasty, a large number of European missionaries came to and became active in China with the discovery of sailing routes to the Far East. Unlike The Travels of Marco Polo, the writings and records of travels by the numerous missionaries focused on the rich and accurate description of specific knowledge. These records became the basis for Westerners to gain a broad understanding of the real China.

Liu Linghua, an assistant research fellow from the Institute of Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said that the Wanli Period is regarded by academia as the beginning of the Westward spread of Chinese learning in the strict sense.

During this period, missionaries introduced modern Western natural science knowledge to China through translation. Liu Xiaoting, a professor from the School of Philosophy at Beijing Normal University, said that the Eastward spread of Western learning has occupied the focus of cultural comparison for a long time, which has given people the wrong impression that the exchange of Eastern and Western cultures has been one-directional.

In recent years, overseas Sinology materials have increasingly made scholars aware that the influence of Chinese culture on Europe far exceeds people’s imagination, Liu Xiaoting said, adding that Chinese culture has had a wide and profound impact on Europe, involving science and technology, culture and art, philosophy and other aspects. This process came to be known as the Westward spread of Chinese learning.

There is a two-way communication between the two civilizations. Liu Linghua said that the Eastward spread of Western learning and the Westward spread of Chinese learning almost went hand in hand. The two dissimilar cultures have complemented each other’s strengths, with both conflict and integration.

Ren said that with the translation of the Four Books and Five Classics—the canonical works of Confucianism—Chinese culture deeply influenced the founders of modern Western philosophy, including Gottfried Leibniz, Voltaire, Montesquieu and François Quesnay.

When many European thinkers were looking for intellectual resources for transformation, distant Eastern thinking became a valuable treasure. Liu Xiaoting said that Pierre Bayle, a forerunner of the Enlightenment, absorbed Chinese ideas of tolerance, atheism and ethical philosophy.

Among the world-class thinkers of the 17th and 18th centuries, Leibniz was probably the one who showed the greatest interest in and had the highest evaluation of Chinese culture, setting a model for Chinese-Western cultural exchange, Liu Xiaoting said.

Voltaire, a leader of the Enlightenment, is a typical example of the spread of Chinese thought in France. His An Essay on Universal History, the Manners and Spirit of Nations (1756) talked about China’s history, culture, ethics and science.

Montesquieu discussed China’s laws, ethics and religion. Quesnay, a physiocratic economist, highly praised Confucius’ practical philosophy.

Literature has also been an important channel for Westerners to understand Chinese society and culture. Ren said that French missionaries including Joseph Henri Marie de Prémare and Antoine Gaubil contributed significantly to the dissemination of Chinese literature in the West.

Inspired by de Prémare’s translation, Voltaire adapted The Orphan of Zhao, a thirteenth-century Chinese play attributed to Ji Junxiang, into L’Orphelin de la Chine, a play that caused a great sensation after performance in Paris.

Hau Kiou Choaan, or The Pleasing History, a seventeenth-century Chinese novel translated and revised by British scholar Thomas Percy, immediately caught the attention of the Western Sinology community after its publication in 1761. Later, the English version was translated into French, German and Dutch.

The Westward spread of these Chinese literary works drew a lot of attention in Europe. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, after reading extensively including Chinese literary works, made some theoretical explorations and conceptualized Weltliteratur (world literature).

In the early period of the Enlightenment, most of the thinkers appreciated Chinese philosophy. When the Enlightenment was coming to an end and Eurocentrism was on the rise, Europe began to be increasingly negative about Chinese culture, Liu Xiaoting said.

As Liu Linghua observed, whether it be high appreciation or negative evaluation, it was inevitable that Western Sinology would misunderstand Chinese culture.

Yue Daiyun, a professor from Peking University, said that in recent years, overseas China studies is no longer simply motivated by curiosity, interest and cultural plunder. Rather, more Western scholars are examining the problems of the West and the world with a diversity of mindsets, questioning the West itself.

(edited by JIANG HONG)