Field study refreshes rural communication research

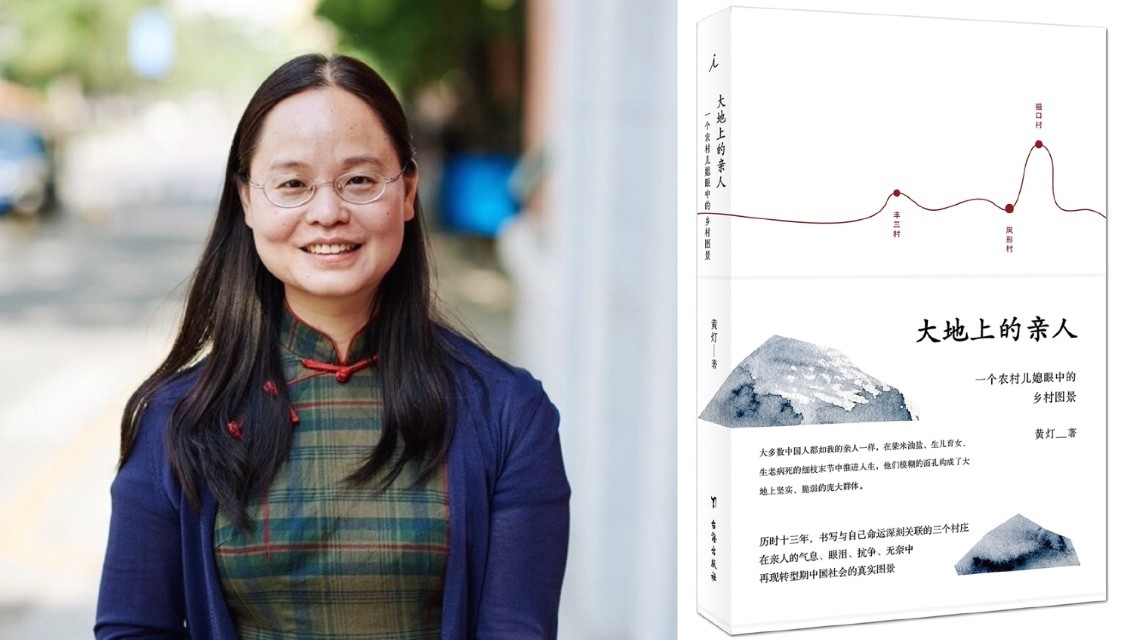

Huang Deng, a professor of communications at Guangdong University of Finance, and her work My Folks in the Countryside: Rural Landscape in the Eyes of A Rural Daughter-in-Law

In its national development strategy, the Chinese central government has prioritized rural areas in recent years. The evolution of communication technologies in the internet age has brought drastic changes to the communication landscape in rural areas, spawning new tendencies and paradigms in contemporary rural communication research.

Zhao Yuezhi, a professor of communications at Simon Fraser University, said that rural issues should be a focus of the efforts to reconstruct communications as a discipline domestically. Most of the previous studies on rural communication have been confined to development, with an emphasis on such topics as how communication technologies advance rural development.

Currently, within the scope of urban-rural relations, scholars have taken history, culture, ecology, labor and new media as starting points while constantly widening the scope of research through the critical lens of political economy of communications.

Growing numbers of scholars are venturing out of universities to conduct field research in the countryside to obtain the latest information and deepen their insights into problems. In doing so, their studies are more down-to-earth while their own subjective points of view are integrated with farmers’ perspectives, broadening the academic horizon and refreshing modern rural communication.

Ethnography

Ethnography originated from cultural anthropologists’ investigations into exotic ethnic groups and cultures in the 20th century. Social anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski pioneered the methodology of participatory observation in his examination of the ceremonial exchange system Kula Ring on the Trobriand Islands off the east coast of New Guinea.

Through observation of his hometown in Kaixiangong Village in Wujiang County, Jiangsu Province, and his townsmen, Chinese pioneering sociologist and anthropologist Fei Xiaotong wrote Peasant Life in China: A Field Study of Country Life in the Yangtze Valley, which was hailed by Malinowski as a milestone in the history of anthropology.

In recent years, ethnography has become increasingly popular as a methodology for researching rural communication. Guo Jianbin, a professor of journalism at Yunnan University, argued that ethnography has three major requirements: trying every means to blend into the everyday life of the research object, examining every facet of the object’s life, and pursuing “in-depth description” to explain phenomena.

Through ethnography, scholars have delved into multiple aspects of rural areas, such as communication media, cultural change and rural reform, providing references for ethnographical studies.

With the popularization of new media, many scholars have begun to return to their hometowns and utilize the internet to publicize rural areas, creating hot topics and broadening communication channels.

In November 2010, a fieldwork titled China in Liang Zhuang, which was authored by Liang Hong, an associate professor of Chinese language and culture at China Youth University for Political Sciences, drew extensive attention to “writing in one’s hometown.”

In 2015, Wang Leiguang, a doctoral student from the Department of Cultural Studies at Shanghai University, returned to his hometown during the Spring Festival and portrayed the culture and evolution of the village in the book Hometown Records by A Doctoral Student. In 2016, Huang Deng, a professor of communications at Guangdong University of Finance, compiled My Folks in the Countryside: Rural Landscape in the Eyes of A Rural Daughter-in-Law.

The two books received much attention because they probed such hot social issues as left-behind children and seniors, care for the aged and housing demolition. At the same time, they were also criticized for being condescending and overemphasizing the negative aspects of rural areas.

In 2018, Chinese technology giant Sina Corp joined forces with an alliance of doctoral students, who were devoted to exploring rural areas, to live broadcast their journey to their hometowns, thus creating a new form of online ethnography.

Regarding rural communication, “writing in one’s hometown” has double significance. Scholars’ observations of their hometowns are communicated through popular, sympathetic forms. With the help of new media featuring broad audiences and fast communication, their direct depiction of rural issues evokes public empathy. “Writing in one’s hometown” has also become a new subject of rural communication research, as evidenced by a number of related studies in recent academic journals.

Ethnography is a type of immersive observation and cultural reflection. As communication technologies develop and the threshold of media access through platforms like live streaming lowers, “online ethnography” breaks spatial and temporary limitations. The layered perspective of “writing in one’s hometown” is a new tendency in rural communication research.

Participatory communication

A misguided approach to rural communication research is to regard farmers as research objects lacking in discourse power, while neglecting their subjective initiative and the crucial role they can play in research.

In this regard, Bu Wei, a research fellow from the Institute of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, proposed action-oriented communication research and stressed media empowerment. Bu said that empowerment is a process by which marginal groups regain their due rights and subjectivity and the ability they develop to effectively exercise their rights.

In the case of rural communication, if farmers were guided to empower themselves by using and participating in media, their power and rights in discourse, economy, culture and social capital could be enhanced.

In the process, scholars have gone deep into settlements for migrant workers in suburbs. They not only participate and observe but also pay attention to training farmers and awakening their master consciousness.

For example, Pinggu District and the Picun Village in Chaoyang District beyond the Fifth Ring Road in Beijing are the theater of organizations like the New Workers Art Troupe. Bu Wei stayed with them all year round, taking part in their activities, training and communication. She even taught her students there. Some of her doctoral students joined the “Wildest Band” consisting of female workers, creating music and giving performances truly together with the New Workers group.

In addition, scholars from universities, such as Zhang Huiyu, a research fellow and assistant professor of communications at Peking University, and Meng Dengying, an associate professor of Chinese language and culture at China Youth University of Political Sciences, served as volunteer teachers in the Pingcun Literature Group, learning literary classics and exchanging views on literary creation with workers.

Their deeds inspired migrant workers represented by Fan Yusu to proactively express themselves on new media platforms, introducing their work, life, dignity and dreams in cohesive literary and art forms.

These erudite and motivated scholars interacted organically with migrant worker groups. They communicated on an equal footing and inspired each other. Meanwhile, they spoke through diverse media forms like exhibition, song and dance, ballad, opera, literature and WeChat to make migrant workers’ living conditions and intellectual demands better known to the outside.

Through participatory communication, the scholars leveraged media empowerment to tap the potential and arouse the subjectivity of individual migrant workers living in cities, hence providing an endogenous, dynamic new paradigm for rural communication studies.

All in all, the countryside is the frontier where contemporary China is undergoing drastic changes, and it is the key to exploring future development of the nation. Rural communication is a crucial field of communication studies. In recent years, scholars’ “writing in their hometowns” and participatory communication have contributed new paradigms to the methodological system of communication research, extended the imagination of sociology, and constructed new discourse and cultural spaces.

By stimulating the subjectivity of farmers, scholars inspired them to express their rights. From a bottom-up observation angle, the logic behind the internal structure of farmers’ groups is revealed.

Li Bin, deputy dean of the School of Journalism and Communication at Tsinghua University, said that the reconstruction of Chinese communications cannot afford to overlook rural areas, farmers and urban-rural relations. Instead, more attention should be paid to the subjectivity and creativity of hundreds of millions of farmers. They should be regarded as masters and creators, not objects of charity, attention and communication.

More valuably, after returning to their hometown, scholars not only reflect on their relations with the countryside and farmers during their research, but also help farmers foster master consciousness and build up cultural confidence, thereby gaining a bigger say.

They advance with the times, taking advantage of convenient resource integration in the social networking era to enrich research paradigms constantly through practice. These practices have made academics more vigorous, far-reaching and profound while contributing new wisdom to China’s rural revitalization strategy.

Liu Nan is from the School of Journalism at Renmin University of China.

(edited by CHEN MIRONG)