Chinese phonology: from archaic to modern sound

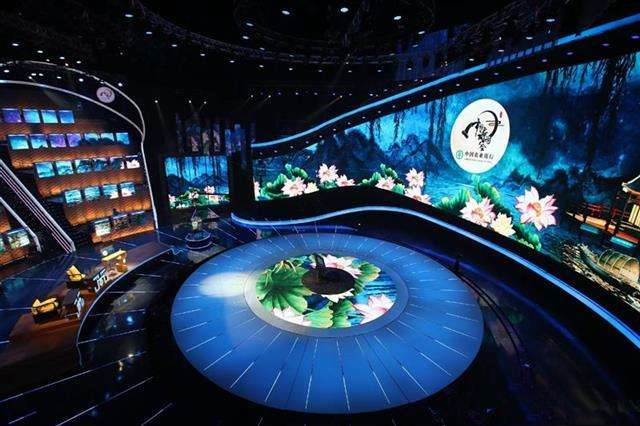

The Chinese Poetry Competition in the third quarter ended on April 4. The TV program remains its popularity and reminds people of the rhythmic beauty of ancient Chinese poetry.

With the TV show Chinese Poetry Competition going viral, audiences now have an opportunity to appreciate the rhythmic beauty of Chinese poetry. Researchers of Chinese historical phonology have indicated that the pronunciation of some Chinese characters in classical poetry is very different from that of contemporary Chinese. It is therefore possible that the original meaning of this poetry may be misinterpreted. Thus, scholars are attempting to discover elements of the ancient pronunciation system to discover changes between ancient and modern Chinese.

Scholars generally divide the history of Chinese phonological evolution into archaic Chinese phonology that existed from the pre-Qin period to the Han Dynasty; ancient Chinese phonology that was alive from the Wei, Jin to the Sui and Tang dynasties; and modern pronunciation of the Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties. Feng Zheng, a professor from the School of Arts at Capital Normal University, said the biggest difference between archaic and modern sounds is that the former has a large number of initial consonant clusters, which no longer exist in ancient phonology.

Zheng Wei, a professor from East China Normal University, said that Chinese phonetics has experienced tremendous changes, in a period spanning the origin of the civilization right up until the present. In addition to the disappearance of initial consonant clusters, there have been changes related to labiodental and retroflex initials, tones, the simplification of rhyme tails, and the appearance and disappearance of head vowels. Feng’s research program “Formation of Beijing Dialects from a Historical Phonological Aspect” was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China and helped probe these issues.

“Chinese phonetics has both differentiation and confluence in its development, but it is mainly headed towards simplification. This is a characteristic of the evolution of initials, vowels and tones,” said Sun Yuwen, a professor from Peking University.

In his research, Sun also discovered that the North has always been China’s political and cultural center. The Chinese language has changed rapidly as a whole in the North but it changed slowly in the South, and the latter has retained more ancient phonetic components. In the history of the Chinese language, there has always been the tendency of the Han nationality to synthesize regional sounds into their standard language, and there has also been a tendency of differentiation of regional sounds. These two trends have jointly advanced the development of Chinese historical phonology.

History has left a lot of valuable research materials for the study of historical Chinese phonology. Sun said that these materials are partly fragmental and partly systematic, while partly handed-down and partly unearthed, containing both standard language and regional sounds. For instance, traditional phonology, philology and critical interpretation of ancient texts together constitute the “rudimentary studies,” an attachment to study of Confucian classics, category in the Complete Library in the Four Branches of Literature of the Qing Dynasty. It contains the research on phonology of previous scholars before the reign of the Qianlong Emperor.

Feng said that the research focus of the phonological studies before the end of the Qing Dynasty was on the acknowledgment of the ancient phonology through the study of archaic and ancient sounds. He added that scholar Qian Xuantong’s (1887-1939) commencement of the phonology course at Peking University in 1918 marked the beginning of Chinese phonology as a modern discipline in China. Chinese phonologist Gao Benhan’s book The Study of Chinese Phonology also had a great influence. By the 1960s, more and more domestic phonologists believed that many of Gao’s theories, methods and conclusions were worthy of discussion and improvement.

One of the major growth points for future research should be in the fields of modern sounds. Feng said according to statistics, there are more than 200 kinds of literature of rhyme books and charts on modern sound, but many related studies are inefficient.

Archeological excavations in recent years have offered new materials for the study of Chinese historical phonology, especially archaic sound research. They contain a large number of interchangeable characters, reflecting important phonological phenomena, which can confirm or modify existing research results. However, research on archaic phonology is also a current bottleneck.

Sun added that since the Chinese language is a linguistic symbol system that combines sound and sense, studies of Chinese historical phonology must pay attention to the relationship between sound and sense. The ideal sound value must set to conform to sound class. The ancient phonetic composition must first be supported by the sound class. The consciousness of “history” must be strengthened, and the research on rhyme of different stages should be examined based on the long history of phonetic development. It is necessary to focus both on the exploration of internal evidence of each period of Chinese language, and on the use of scientific and reliable linguistic theories.

ZHANG QINGLI is a correspondent with Chinese Social Sciences Today.

(edited by JIANG HONG)