Chinese philosophy should reach out to nation’s issues

The biggest misconception about the field of Chinese philosophy is that it entails merely studying the history of various schools. While researching history is certainly a major task, it is not the only one. Studying issues of the nation from philosophical perspectives is another important mission that Chinese philosophers should shoulder.

The term “Chinese philosophy” consists of two parts: “Chinese” and “philosophy.” That means Chinese characteristics are indispensable to the concept. In this vein, Chinese philosophy should be based on China’s cultural experience, focus on national issues, and place Chinese topics on par with fundamental and common issues of human philosophy.

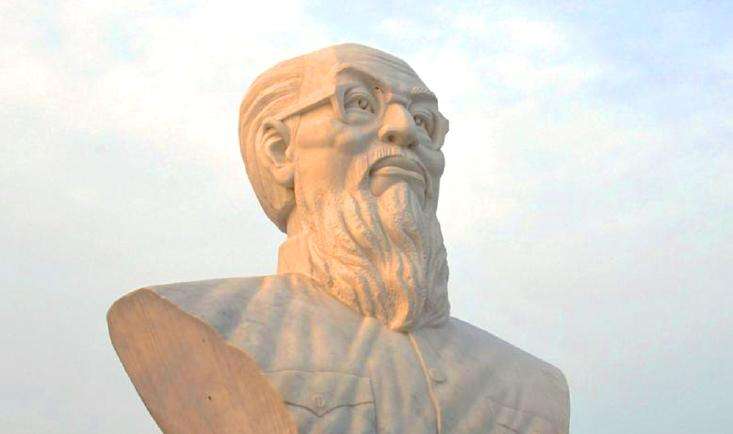

A few problems merit attention in current studies of Chinese philosophy. First, Confucianism plays a dominant role. In the 20th century, Chinese philosophers were evenly distributed to each subfield, but in the past two decades, Confucian scholars have had absolute predominance.

Moreover, studies of Confucian classics have gained steam. Renowned Chinese philosopher Feng Youlan (1895-1990) ushered in an era of neo-Confucianism, but in the past decade, the focus has gradually shifted to research of Confucian classics.

At the same time, the influence of ritual theory in Confucian classics has been increasing. For one thing, scholars devoted to research of rites are strong academically. For another, ritual studies are closely related to many practical issues of contemporary China, so they resonate more easily with Chinese academia and attract social attention.

These changes in Chinese philosophical studies show the tendency for the discipline to directly respond to Chinese issues. The awareness of caring about, contemplating and leading society has grown among Chinese philosophers.

However, a lot of problems are under the surface of the changes. For example, Chinese philosophy originally had rich intellectual resources it could use to cope with modern issues, yet in the present research landscape, areas outside of Confucianism, such as Taoism, Buddhism and studies of pre-Qin philosophers, have been marginalized. In addition, many propositions in Confucian classics have been mechanically implanted into modern political discourse, giving rise to various absurd political views.

Determining what kind of Chinese philosophy contemporary China needs is a big issue facing researchers. They should, first of all, build a holistic academic vision, including a comprehensive, deep and up-to-date understanding of Chinese philosophical traditions. Neither neo-Confucianism nor Confucian classics alone is sufficient to understand the whole of Confucianism. We cannot grasp Chinese thinking traditions with a simple Confucian outlook, either.

While updating our understanding of the Chinese philosophical tradition, we should refresh our knowledge about world philosophy. To this end, Chinese philosophical researchers should change the mindset when reading Western works. Especially, they should stop regarding Western philosophy as a methodology or tool. It is important to remain grounded on the developmental course of Western learning to open up the horizon from which we make sense of Chinese philosophy.

In addition, they should take the entity of Chinese civilization as a starting point to digest features of Chinese philosophy. As a core element of Chinese civilization, Chinese philosophy is enmeshed in the history and culture community that it relies on. It was not only created out of the production and life of Chinese people, but also crystallizes wisdom the people have drawn from the course of the civilization and contributed to the human intellectual world. Furthermore, the great, inclusive, graceful and delicate Chinese civilization is inseparable from Chinese philosophy, a unique part of human intellectual life.

In pursuit of the great rejuvenation of the nation, Chinese philosophers should decipher the Chinese civilization as a whole and back it up in reality. To fulfill the mission, they should view social reforms, institutional changes and evolution of ideas in Chinese history dialectically. It is likewise necessary to realize that the inner, profound unity of society, institutions and ideas is the precondition and basis of civilization.

Last but not least, it is essential to change the problem orientation and research methodology, which requires a profound reform of the concept of history. In Chinese philosophy, it can take the share of the rejuvenation of historical and political philosophy.

Probing the historical and political character of China as a history and culture community is the foremost topic for Chinese philosophers to serve the civilization. In this way, the historical and political nature of early Confucian classics, pre-Qin philosophers and even classical historiography, will also be rediscovered.

Li Changchun is an associate professor of philosophy at Sun Yat-Sen University.