Rescue project aims to compile academic development of Chinese veteran scientists

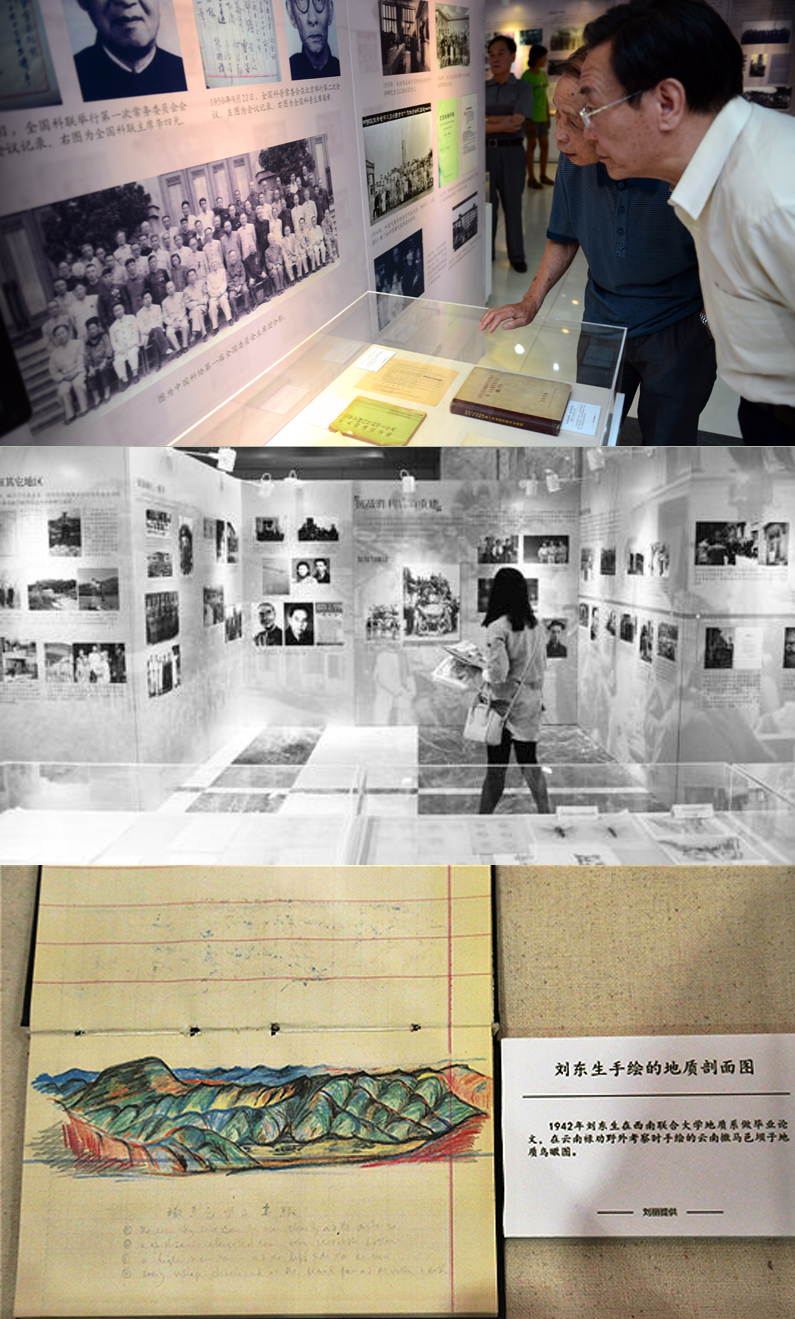

Visitors look at the displays at an exhibition on contemporary Chinese scientists that toured across China. Materials collected in the project were also showcased.

It was Women’s Day when 90-year-old Liu Dongsheng finished orally recording his last tape. The tapes—40 in total—are a testament to his whole life. To whoever might listen one day, the member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) carefully spoke into the recorder in a low voice: “Happy Women’s Day.”

Liu Dongsheng recorded for almost a year and put the tapes in a small plastic box. He died in 2008. Seven years later, Zhang Jiajing, a lecturer from the CAS university, heard the recorded blessing while working on the rescue project.

Of the first 50 scientists selected to have their careers chronicled, but only a few are still living.

“Most of us would think of He Zehui and Qian Sanqiang when it comes to that period of time. However, many scientists who are not well known among the public have made great contributions in their legendary lives. They are passing away,” said Zhang Jiajing.

Irreplaceable rescue

Born in 1914, phytotaxonomist Zhang Hongda spent most of his career exploring China’s mountains in search of specimens. He discovered seven new plant genera and nearly 400 new species. At the age of 71, he joined an expedition in the Himalayas. But when Guangzhou Library staff member Zhang Xiaohong asked him about his academic life, he chose to reminisce instead about his elder brother and himself catching fish in the clear river that flowed through his hometown.

Zhang Hongda was the first scientist that Zhang Xiaohong interviewed for the project. The deadline was approaching. At first, she considered it a task. She searched various keywords in the database in a bid to understand the scientist’s academic development. For a long time, half of her bed was taken up by materials and her mind was filled with the important milestones of the scientist’s career.

Zhang Hongda’s personal files were archived at Sun Yat-sen University and could not be photocopied without permission, so Zhang Xiaohong sat in the archive for a month, copying a 4-centimeter-thick stack of documents by hand without noticing that she had fallen in love with this work.

Zhang Xiaohong wanted to finish compiling materials on Zhang Hongda and other scientists as soon as possible. Underlining the urgency of the task, anatomist Zhong Shizhen said, “People at our age are like candles. You can see light, but the candles can be blown out at any time.” He never avoids talking about death and still works in his 80s.

Some memories can resist time. Zhang Hongda proposed a classification system of spermatophytes in 1986. Unlike the traditional classification with only two subdivisions, Zhang Hongda divided Spermatophyta into 10. When Zhang Xiaohong asked him to explain the theory, the veteran scientist promptly stretched out his clenched fist and then suddenly straightened five fingers, saying: “one origin and multiple systems.”

Zhang Xiaohong was shocked. The old man in front of her was “so powerful and, to some extent, fierce,” as if he were “defending something.” Only one who conducted the research for all those years with his heart and soul could explain such a complicated theory with a simple gesture. Nobody can replace him, she said.

Zhang Jiajing heard the wind blowing across China and the ever-changing earth in the recordings of Liu Dongsheng. She majored in geographical science as an undergraduate and chose disciplinary history as the focus of her doctoral studies. It was a precious opportunity for her to learn more about the “hypothesis of eolian origin for loess” from Liu Dongsheng, a winner of the State Preeminent Science and Technology Award, the highest scientific prize awarded in China. German geographer F. Richthofen proposed the theory in 1877 and Liu found strong supporting evidence for it.

“There are two kinds of scientists. Some are extremely smart, and some are not, just like me. Young scientific workers can draw on my experience,” said Liu Dongsheng at the beginning of the recordings, revealing the primary goal for reviewing his whole life.

All of these recordings were collected in the base, particular set for the project, in the library of Beijing Institute of Technology. The 1,000-square-meter space reflects the development process of Chinese sciences.

Witnesses of history

Workers involved in the project are mainly from research institutes and universities under the CAS. They have never heard of many scientists that they were going to interview, but they were so amazed about the legendary experience of these people after studying relevant documents. These not-so-familiar names include researchers of China’s first reaping machine, the first pair of silk stockings and other items. “Each of them is a key to a door behind which hides the details of that period,” said Zhang Jiajing.

Physicist Hong Chaosheng is a CAS member. Tears bathed his cheeks as he recalled a moment in 1931 when all his classmates cried bitterly upon hearing their teacher read a piece of English news about the September 18th Incident.

Another precious work by Hong was found in a pile of old documents. It was a graph paper printed with the logo of Purdue University, where Hong studied in the United States. On the paper, the 29-year-old student drew China’s national flag whose five stars were precisely sketched, using a compass and ruler.

At that time, Hong had received three invitations from European labs, including the opportunity to work with the renowned British physicists Nevill Mott, who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1977 for his work on the electronic structure of magnetic and disordered systems. However Hong decided to come back to his home country after hearing about the founding of People’s Republic of China.

Commemorating scientists

Ju Gong, a neuroanatomist and CAS member, understands that the world surrounding him is changing, but his zero tolerance of academic misconduct has never abated throughout his life. Two of his graduates conducted misbehaviors in scientific research. He insisted on asking the students to drop out because the misbehaviors would be recorded in their personal files if they were compelled to leave the university. Since then, Ju’s graduates have never conducted similar misbehaviors.

Ju has high expectations of his students. People have compiled an autograph album for him each year. Unlike paper collections and achievement reviews, Ju’s autograph albums consist of articles written by his students about their academic achievements and reflections after graduation.

Zhang Xiaohong was relieved that the book, based on the collected materials of Zhang Hongda, was published before his passing. The book title was two lines of a Zhang Hongda’s poem, meaning that his ambition never changed as he travelled to numerous mountains and he gave all his passion to botany. The book is among the project’s first batch of book collections. The 100th book of this series was released this May.

Zhang Xiaohong said sometimes she felt that she would have made better choices in her career if she had met the veteran scientists earlier. Born in the 1970s, she feels she needs to make greater efforts in the academic field, sometimes being disappointed because she has failed to meet her own expectations. By contrast, when the experience of these veteran scientists come to her mind, “my worries are not worth mentioning at all,” she said.

Zhang Jiajing was eager to accomplish the mission at first, but she felt a little lost now that it is done. She said: “There are no tapes that I can listen to in the future.” She still remembers Liu Dongsheng’s small balcony, empty but filled with sunshine, when she visited the apartment for the first time. Liu started recording his life there and seven years later, she discovered his voice in the dust of time.