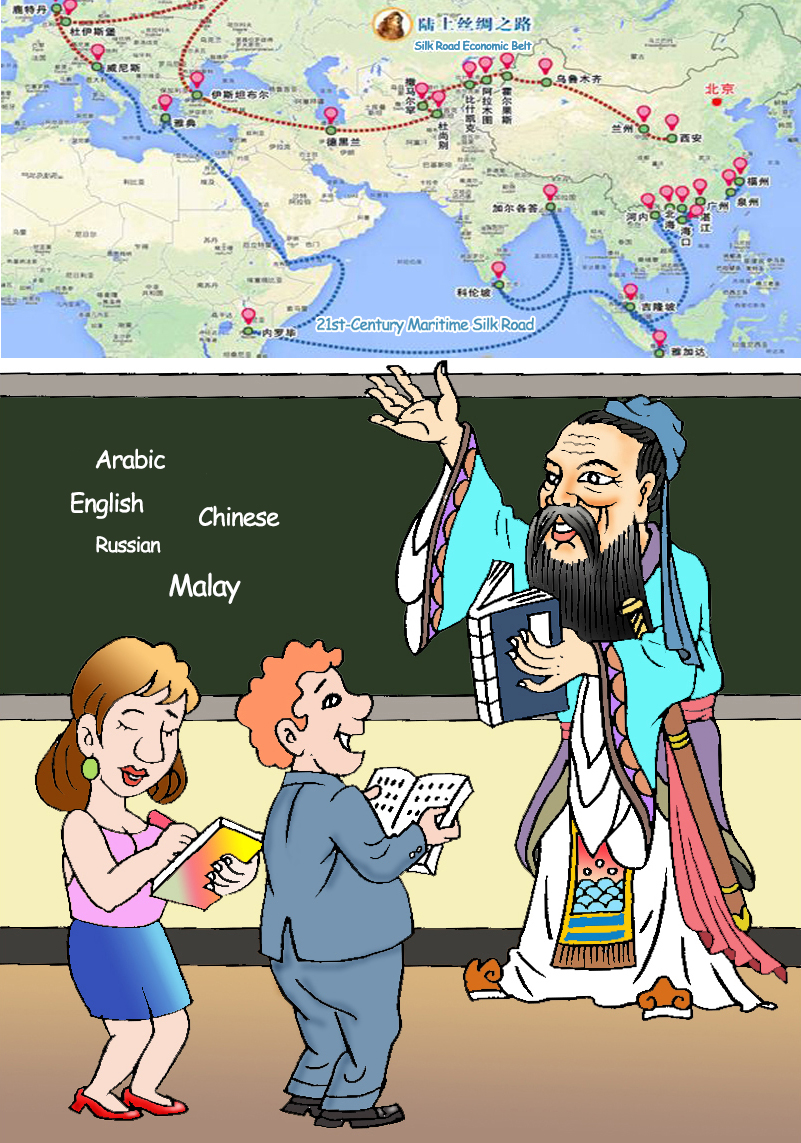

Language talent needed to support ‘B & R’ initiative

Tongue ties

Cartoon by Liu Zhiyong; Poem by Long Yuan

The “Belt and Road” has a far-reaching span,

But language barriers potentially hinder the plan.

Relationships between nations and peoples are warming.

Friendly ties in trade, finance, logistics and traveling are forming.

To achieve “five major goals,” requires more teaching.

Through learning language, out-stretched hands are reaching.

Official languages are essential,

But native dialects are also fundamental.

Only when we get rid of such a stumbling block,

Can the “Belt and Road” truly be a melting pot.

Established more than two millennia ago, the Silk Road linked the major civilizations of Asia, Europe and Africa. To carry on its historical legacy, Chinese President Xi Jinping put forth the initiative to jointly build the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road in 2013.

The “Belt and Road” initiative can promote political trust, economic integration and cultural cooperation between China and other countries along its routes in the contemporary era, thus building a community of common interests, responsibilities and destiny. The realization of such a vision should strengthen cross-language communication, based on which economic, trade, cultural and interpersonal exchanges take place.

According to preliminary statistics, the 64 countries along the routes of the “Belt and Road” use nearly 2,500 languages, accounting for more than one-third of the languages spoken on the planet. And eight of these countries each use more than 100 languages domestically. In such a complicated linguistic context, it is important to understand the language situation in each of these countries in order to achieve cross-language communication.

Official language

Based on different requirements for communication, languages of these countries can be classified into three kinds: the official language explicitly mandated by law, the common language used by most people in a country or generally used in social life, and dialects of official and common languages as well as ethnic minority languages. Official and common languages are the foundation of cross-language communication at the present stage, while for in-depth exchanges, it is necessary to learn variants of official and common languages as well as ethnic minority languages.

Among the 64 countries along the routes, only the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina does not have an official language written into its constitution. Among the other 63 countries, 50 have only one official language, respectively, and 12 have two official languages. Singapore has four official languages: English, Malay, Mandarin and Tamil.

A country that has several common languages tends to accord official status to more than one language. For instance, in Afghanistan, Dari and Pashto are the most widely spoken and official languages. Nearly half of the national population speak Dari while about 35 percent speak Pashto. In Sri Lanka, the official languages are Sinhalese and Tamil, the speakers of which constitute more than 90 percent of the national population.

In addition to their own languages, countries that were once colonized also use the languages of colonial powers as an official language. The languages of colonial powers have become the working language in such areas as politics, economics, education and culture in these countries.

For example, in India, Hindi and English are official languages. However, less than 5 percent of the national population can speak English well, and at most, 15 percent can speak English if those who have just a basic fluency are included. This 15 percent constitute the elite class that plays a dominant role in guiding India’s social life.

Singapore, Bangladesh, the Philippines and Pakistan, which were once colonized by the United Kingdom or the United States, use English as one of their official languages. Once colonized by Portugal, East Timor uses Portuguese as one of its official languages though only about 7 percent of the national population can speak it.

Among the official languages of the 63 countries, Modern Standard Arabic is used by the most countries: the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Yemen, Jordan, Egypt, Bahrain, Qatar, Palestine, Lebanon, Iraq and Israel. English is used by the second most countries: Pakistan, the Philippines, Bangladesh, India and Singapore. Russian is used by Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Malay is used by Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore. Tamil is used by Sri Lanka and Singapore.

Excluding Mandarin, a total of 54 official languages are used by nations along the routes of the “Belt and Road,” covering the major language families, such as Sino-Tibetan, Indo-European, Ural, Altaic, Semito-Hamitic, Caucasian and Dravidian languages.

Common language

There are no specific standards for common languages. For most of these countries, the official languages are also their common languages. For instance, in Albania, nearly 99 percent of people speak Albanian, which is both the common language and the sole official language under the law.

In only a handful of countries, the official and common languages are not the same. In countries whose official languages are Modern Standard Arabic, it is the various dialects of Modern Standard Arabic that are commonly spoken. For example, Egyptian Arabic is the most widely spoken in Egypt while Bahraini Arabic is the most widely spoken in Bahrain.

Moreover, as a result of historical reasons or deepened international exchanges, English, French and Russian have become the most important common languages for Qatar, Lebanon and Georgia in addition to their official languages.

Talent cultivation

To provide better language services, it is essential to enlarge the pool of language talent. In China, 11 of the 56 official and common languages for the 64 countries are not taught in colleges and universities, including Dzongkha, Belarusian, Tetun, Georgian, Montenegrin language, Dhivehi, Moldavian, Slovenian, Tajik, Armenian and Bosnian. Therefore, China is still lacking in foreign language talent.

In recent years, Confucius Institutes have developed rapidly, enabling people all over the world to learn the Chinese language. Among the 64 countries along the routes of the “Belt and Road,” 16 countries, including Oman, Bhutan, Kuwait and Georgia, have not opened a Confucius Institute. Twenty countries, including Slovenia, Lithuania and Croatia, each have opened only one institute. Thailand has opened 14, and Russia has opened 17, making them the only two countries that have opened up more than 10 Confucius Institutes.

Universities in 28 of the 64 countries, including Oman and Afghanistan, do not offer the Chinese language as a major. Some of these universities offer courses or have established a center to teach Chinese. For instance, the Yerevan Brusov State University of Languages and Social Sciences in Armenia offers a course on translation from other languages to Chinese. Moldova State University has set up a center for Chinese language, providing opportunities for about 30 Moldavian students each year to learn Chinese language and traditional culture.

In addition, 25 countries, including the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Pakistan, have one to five universities that offer Chinese as a major. Eleven countries, most of which border China, have more than five universities that offer Chinese as a major, with more than 300 universities in Russia, 55 in Thailand and more than 20 in Vietnam.

In China, there are no courses on official and common languages of Bhutan, East Timor, Georgia, Maldives and Moldova, while the five countries do not have Confucius Institutes. Georgia and Maldives each have a university that offers Chinese as a major, while there is no Chinese major in the other three countries.

Montenegro, Slovenia and Armenia each have a Confucius Institute but do not offer Chinese majors. The official languages of the three countries are not taught in China. As a result, China has a large language barrier with the aforementioned eight countries. Furthermore, eight countries, including Albania and Estonia, lack the ability to provide language services in the implementation of the “Belt and Road” initiative.

In a word, detailed investigation and research on language are needed to lay a foundation for cross-language communication between nations along the routes of the “Belt and Road.” And this relates directly to the success of the construction of the “Belt and Road.”

Liang Linlin and Yang Yiming are from the Collaborative Innovation Center for Language Ability at Jiangsu Normal University.