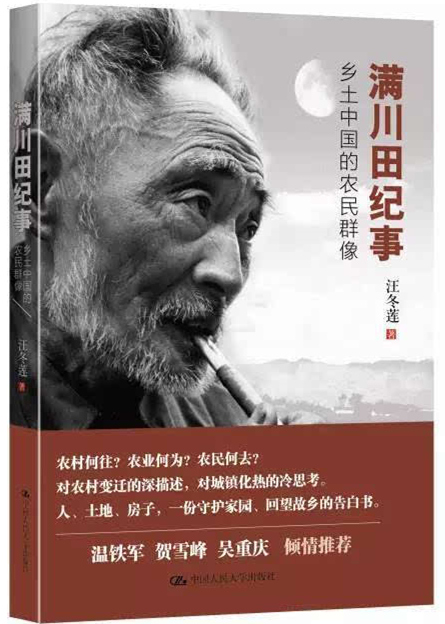

Farmers in an age of transformation

Stories of Manchuantian Village

Author: Wang Donglian

Publisher: China Renmin University Press

Ever since the 1980s, China has been transforming from a traditional agricultural society to a modernized, industrialized and urbanized society. It is no exaggeration to say that more changes have taken place in this time than in the past 5,000 years. The universal law of social development indicates that urbanization is a spontaneous migration process from rural to urban areas, and is generally slow but stable. However, beginning in 2013, the central government of China introduced a series of policies to encourage migrant workers to settle down in cities and towns, which greatly accelerated the urbanization process.

The country is vigorously promoting a new model of urbanization and the marketization of rural collective construction land. A number of processes are being streamlined at the grassroots level, such as the right to farm arable land. Authorities are also implementing processes relating to land transfer methods such as mortgages, and streamlining the ways property rights for rural homesteads can be transferred. These steps aim to actualize wealth from rural land that has been dormant for decades and assist people in promoting the rapid changes occurring in traditional agricultural society.

In order to record the evolution of the lives of those who have grown up in the soil since ancient times, and also to record their endeavors and conflicts along with the contrasts between conservatism and changes, I chose my hometown as a point of focus. This place is called Manchuantian Village, a village of about 1,000 people located in the mountain area of Huangshan city, Anhui Province. I endeavored to create a panoramic description of social changes that happened in an inland village over the past 40 years. My work is dedicated to the great era of change, to those farmers who are destined to stay in the country in this wave of urbanization.

In the book, I describe in detail the changes in farming practices in rural areas over the past 40 years, the gradual changes in the marital market, the improvement of traffic conditions, the disintegration of the necessity to carry on the family line, the loss of traditional customs, and the changes in the appellation of family members. I also highlight how migrant farmers fully tapped the potential of the native products in the mountain village to achieve economic self-reliance. They have experienced both joy toward their integration into the city, and the grief brought by pain or even death. The book also showcased the rural areas in central and western China against the urbanization and marketization tide: people who weren’t classed as farmers still practiced extensive agricultural production management, and a large number of mountain farms were abandoned; villages shrunk, and gambling has become the most viable method of entertainment in rural areas.

At the end of the book, I point out that history has pushed our generation toward this mission. We must inherit the legacy of farming civilization, while surpassing quality and investment of the agricultural production model of 30 years ago in order to make up for what we owe. The community-supported agriculture production model is the only way to save chemical agriculture, which is the mainstay of China’s current agriculture.